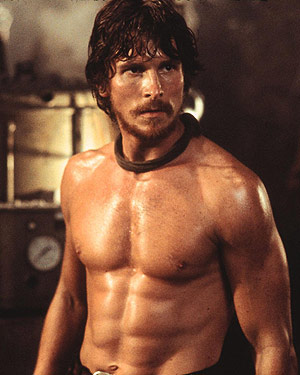

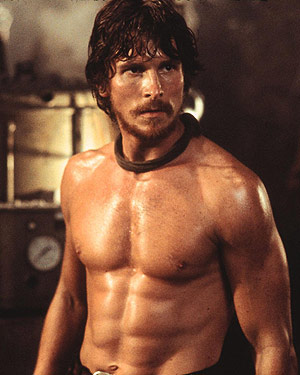

Beware. There are odd and madly scheduled movie channels that you will only find in hotel rooms. This is where slasher movies appear at lunchtime (I caught part of a particularly disturbing film called Ginger Snaps) and kids movies come late at night (Babe: Pig in the City). Oddest of all is this entry in the CV of Christian Bale. Reign of Fire (2002) is set in a post apocalyptic near future (alarm bells are already ringing when I discover that this imagined future is only 2020 – I hate it when post apocalyptic films are so short sighted). It’s an English future, and Christian Bale is in charge, clumsily equipped with a Dick Van Dyke cockney accent and wispy beard. Perhaps Mr Bale was advised that people will talk with this odd approximation of a London twang in the future, and perhaps they will, especially in a future where fire breathing dragons are terrorising the human race into extinction. Yes, it’s that kind of film.

Reign of Fire was a nice little starter to prepare me for The Dark Knight. I’d heard a lot about this, mostly regarding Heath Ledger’s turn as The Joker. In a dull, monotonous and pointless film he’s certainly the best thing in it. But even saying that, once I’d sat back I was forced to conclude that any half decent actor would make something out of The Joker, wouldn’t they? And sadly, director Christopher Nolan doesn’t make enough out of The Joker to make it a truly great movie. What is best about Ledger’s interpretation is that he’s deadly serious, which cuts out the ham element which befell Jack Nicholson. Ledger is not much of a joker at all really, although certainly insane. But there’s only a hint of just how dangerous this man is, and the scene reminiscent of The Silence of the Lambs where the dangerous criminal is ensnared is only a pale comparison to the greater movie. And in such a long film they should have spend a little more time on the mad villain’s capture and escape.

Taking its hype into account, The Dark Knight is one of the most disappointing films I’ve seen in years. The sterling cast is wasted; Gary Oldman in moustache and glasses just gives a passable impersonation of Dr Robert Winston, Morgan Freeman and Michael Caine wake up, rub their eyes and turn in their usual roles. And Christian Bale opts for the gruffest of gruff voices when he’s dressed up as Batman, sounding like Clint Eastwood forgetting to gargle after a night on the cigars.

I think it can all be traced back to a problem with the whole ethos of DC Comics, which will never be a patch on Marvel, and for me the recent Incredible Hulk is far superior a film to The Dark Knight. For one thing, it does have something of a sense of humour, although there are too many references to the 70s tv series (a glimpse of Bill Bixby, Lou Ferrigno supplying the Hulk’s voice) and we get the inevitable and now tedious Stan Lee cameo. But The Incredible Hulk rockets along like a superhero film should do. Edward Norton, who I normally find particularly nondescript, is fine as Bruce Banner, and William Hurt and Tim Roth make excellent baddies. And I hope that Christian Bale was taking notes, as Mr Roth has the most excellent London accent.

I didn’t really know what I wanted to be, apart from ending up as an eccentric millionaire. I had to be a millionaire. If I couldn’t do it without being crooked, then I’d have to be crooked. I was quite prepared to do that.

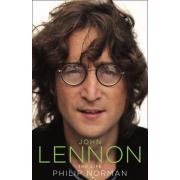

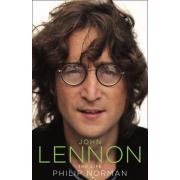

Although I have an unquenchable thirst for anything John Lennon or Beatle related, these pages have been strangely silent over the last two or so years when it comes to the Fab Four. Patiently I’ve waited for a decent new biography to get my teeth into, and now we have Philip Norman’s 822 page John Lennon: The Life. To do Norman’s mammoth work some justice I’m going to spread my thoughts over more than one post. Besides, I haven’t finished it yet. Also I’m away next week and the heavy hardback will take up most of my hand luggage. I’ll have to wait until November to finish it.

There’s been times when I’ve wondered if I’d ever need to read another Lennon biography. I’ve probably read more than my fair share. Strangely, Norman’s other Beatle-themed book Shout, doesn’t stick in the mind much. Ray Coleman’s two biographies of the 80s are much more memorable, and reading them at an impressionable age I held Lennon in the same awe as Coleman. Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon is also unforgettable as it paints such an awful, and often unqualified, picture of him. The Hunter Davies Beatle biography from the late sixties is fun, as is Michael Braun’s Love Me Do, fascinating for being one of the first books published about the moptops. But I suppose my all time favourite is Ian Macdonald’s techy but brilliant Revolution in the Head.

So the question remained, did I need another Lennon book? And reading the opening chapters of John Lennon: A Life I began to worry that maybe I didn’t. A lot of the detail of Lennon’s early life was very familiar, especially his schoolboy exploits with his partner in crime Pete Shotton, and could easily have been cribbed together from the selection of titles I’ve already mentioned. However, Norman kept me reading because I suspected he was looking at this life with the canny eye of the historian. He weighs up the facts carefully and does not commit to making sweeping statements, for example not subscribing to the general view that John’s father was a scoundrel, abandoning the boy and his mother and only returning when he smelt money. Norman draws the picture of a much more complicated story, and for the first time reveals John’s father as not being such a black and white villain, but an unlucky man often prone to unfortunate circumstances.

Norman also handles the well worn legends very carefully, trying to avoid the apochryphal tales. The tragic death of John’s mother when she is run over by an off duty policeman is treated without the sensation of some other biographies, as is the other tragic death in John’s early life. The sudden demise of “fifth Beatle” Stu Sutcliffe aged 22 is related without the usual romanticism, which results in making this loss very moving. And Norman is also careful about the Goldman-fuelled rumour that John was indirectly responsible for his friend’s death by attacking him in a drunken brawl. He doesn’t jump to conclusions about what might or might not have happened because we will never know.

The other turning points in the story arc of the early Beatles are treated with similar care. Norman doesn’t give too much time to the sacking of Pete Best, and, like him, I quietly conclude that it was the right decision to get rid of him. Me, I’m a Ringo man. The supposed gay affair between John and Brian Epstein is also played down; there simply isn’t enough evidence to prove what happened one way or the other. What Norman does do, however, is expose the cruel and dark side of Lennon’s nature that is reliably documented; his violent assualt on a DJ friend that was covered up to avoid a Beatle-ruining scandal, the appalling treatment of Cynthia Lennon, the “secret wife”, and Lennon’s countless affairs.

But he was a mixed up fucker and this made him a great artist. John Lennon: The Life reminded me of one of my favourite books about the 1960s, Dominic Sandbrook’s White Heat. This gives a similarly intelligent, well researched and careful account of legendary, fantastic and life changing events. And you can’t really avoid reading the Beatles and John Lennon story just one more time once you start doing so, especially when it’s put together so well.

Of course I’m only so far; the Fabs have only just released their second album With the Beatles. And listening it again today I’m reminded of its charm, sense of excitement and timeless longevity. So turning the pages still only in 1963 I’ve a long way to go yet. I hope you’ll join me for the rest.

Neil Gaiman is my favourite writer of short stories. His novels are great too, but there’s just something spellbinding about his shorter pieces. The collection Fragile Things was possibly the best book I read last year and certainly one of the best and most memorable books of ghost stories I’ve ever read. The Graveyard Book is his latest work of fiction, and although aimed at a younger readership it still bears Gaiman’s refreshing flair as a gifted writer of supernatural tales.

The Graveyard Book is about a lost child raised by ghosts in an old graveyard, now fallen into overgrown disuse. It’s a simple idea, and its possibly been used before, but only a writer of Gaiman’s class can use it so well. He lets his imagination run with the concept, both through the eyes of the child in question, Nobody Owens (Bod), and through inviting his reader to become immersed in the story. The setting he creates is wonderful, the collapsed and crumbling headstones, the old crypt, the unconsecrated ground, and the ghosts themselves who range from the comic to the creepy. Most of all Gaiman has a wonderful way with words: at one point Bod pauses in conversation to run his fingers over a moss-covered grave, so simply and in so few words reminding the reader they are in the midst of an incredible ghost story.

I’ve mentioned my love for Gaiman’s short stories, and the best parts of The Graveyard Book read like self-contained tales in their own right. Typically for Gaiman, he reveals some of the craft that went into this book in the closing acknowledgments, explaining that he started with the fourth chapter and then later constructed the rest of the book around it. This, The Witch’s Headstone, is a brilliant passage, where Bod encounters and befriends the ghost of a medieval witch. Similarly, another chapter stands out in its own right where Bod plays with a young girl who perceives him as an imaginary friend, only to be found amongst the graves, a friend who’ll fade with memory. Like Gaiman’s best work, it is very touching.

I loved this book throughout, although at times it does feel that Gaiman has strained to wrap a plot around his wonderful prose. I can understand this, as a book aimed at younger readers must appear to be going somewhere, and I may be cynical when I draw comparisons with Harry Potter. But they are there. The child in danger after his parents are murdered, the protection of magic and secrecy, the Dumbledore role as personified by Bod’s guardian Silas. Like Harry, Bod is perceived as a misfit in the “real world”, and like Rowling, Gaiman has a clever line in humour when he portrays those in the magical world who choose to teach and steer our hero.

However, Gaiman has an advantage over J.K. Rowling in that his other fiction is far more varied. Whilst she is yet to branch out from Hogwarts, Gaiman can point his newer readers in the direction of his darker fiction. Passages in The Graveyard Book, in particular Bod’s encounter with the deadly ghouls, recalls the dark and crazy humour of Anansi Boys and American Gods. Most of the readers of The Graveyard Book aren’t quite ready for this very adult stuff, but Gaiman can do that rather wonderful thing in children’s fiction – suggest that there are very broad, challenging and exciting horizons for the reader yet to come.

Previous Page |

Next Page