In a year or two, the older generation that still dreamed of Empire must surely give way to politicians like Gaitskell, Wilson, Crosland – new men with a vision of a modern country where there was equality and things actually got done. If America could have an exuberant and handsome President Kennedy, then Britain could have something similar – at least in spirit, for there was no one quite so glamourous in the Labour Party. The blimps, still fighting the last war, still nostalgic for its discipline and privations – their time was up.

On Chesil Beach examines one evening in the life of a young couple called Edward and Florence, the most important in their lives as they prepare for their wedding night in a Dorset hotel. It’s 1962, and Ian McEwan is knowingly aware of the worldwide cultural changes that are beginning to take place. The novel portrays Edward and Florence as products of a stifling era that will thankfully soon be over – both are sexually inexperienced, the former frustratingly so – and they both face their wedding night with terror. And this is the rub. Such importance has been placed on this experience – this event – this night – that the odds are very high on things going wrong.

There is a sense that McEwan hates this point in history, that he can’t wait for the 1960s to get into swing and for the English to grow their hair and let it down. Even though On Chesil Beach can’t help appearing to view the respective childhoods and adolescence of Edward and Florence as taking part in charmingly innocent times, I still (as a cynic) read a lot of sadness into McEwan’s account of their formative years. Edward’s mentally unbalanced mother, his strange flirtation with physical violence, Florence’s desperately competitive father; it’s all brilliantly subtle writing – the sort of thing that makes McEwan the master he is.

Ian McEwan has a knack for slowing down time, examining events that happen very quickly by reducing them in his narrative to a snail’s pace. The ballooning accident in Enduring Love and a road rage incident in Saturday are two such examples, where he thoroughly examines what is only really a fleeting moment in time. In On Chesil Beach it’s this fateful night, no more than a hour in real time, that is examined so thoroughly and becomes so unforgettable, haunting and poignant.

There’s a point where our most vivid memories become ingrained on our consciences forever. For Edward and Florence it’s this very evening that they spend together on and near to Chesil Beach; still vivid, disturbing and nightmarish to them for the next 45 years. This is the substance of the novel and of their memories. The concluding “catch up” part of the novel – 1962 to the present day – comprises only a few pages; without giving anything away the lives of Edward and Florence are brought promptly up to date. Events since 1962 are insignificant and fleeting – for the reader and for them. For significance as one of life’s major turning points, it really does all happen on Chesil Beach.

On Chesil Beach may appear insubstantial in its brevity but I really believe that McEwan is at the height of his powers, mastering the ability to leave a lot unsaid, and leave a lot to the consideration of the reader. I’ve been rereading one of his earlier novels, The Child in Time, and it’s noticeable how much he has matured, becoming much less laboured as a writer. His prose is graceful, flowing and absorbing. Britain’s greatest living author? He’s getting there.

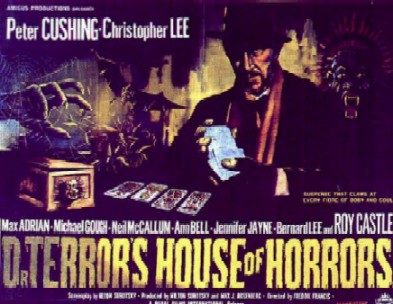

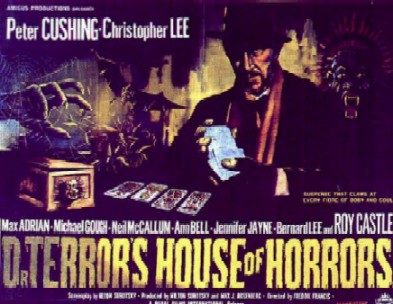

Freddie Francis was a prolific director for film and television, best known for his British horror films of the 60s and 70s. He worked for the two great production companies Hammer and Amicus. Highlights of Freddie Francis’ directing career, providing me with colourful and comfortable late night horror in my formative years, were Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), The Skull (1965), Dracula Has Risen From the Grave (1968), Tales From the Crypt (1972), The Creeping Flesh (1973), Tales That Witness Madness (1973) and The Ghoul (1975).

Although these films are all excellent, he was very much a jobbing director, and there are other films in the Hammer and Amicus canon not directed by him that are equally good. It’s his work as an accomplished cinematographer that has gained him the most respect, including such gems as Room at the Top (1959) and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). Best is The Innocents (1961), a very eerie and disturbing adaptation of The Turn of the Screw by Henry James. This is always worth seeing, and Francis manages to create a menacing monochrome atmosphere that matches the original book. If you haven’t seen it, please make a point of doing so.

David Lynch also employed Francis for The Elephant Man (1980), another black and white masterpiece, and The Straight Story (1999), but I’m only touching the surface of his achievements. See the IMDb for the full story.

Freddie Francis, 1917-2007.

He says there are no bears in this part of the country. What about wolves? I want to know. He gives me a pitying look.

‘Wolves don’t attack people. They might be curious, but they won’t attack you.’

I tell him about those poor girls who were eaten by wolves. He listens without interruption, and then says, ‘I’ve heard of them. There was no sign that the girls were attacked by wolves.’

‘But there was no proof that they were kidnapped, and nothing was ever found.’

‘Wolves will not eat all of a corpse. If wolves had attacked them, there would have been traces – splinters of bone, and the stomach and intestines would be left.’

I don’t know quite what to say to this. I wonder if he knows these macabre details because he has seen them.

‘But’, he goes on, ‘I have never known wolves to attack without being provoked. We have not been attacked, and there have been wolves watching us.’

‘Are you trying to frighten me, Mr Parker?’ I say, with a careless smile, even though he is ahead of me and cannot see my expression.

‘There is no reason to be afraid. The dogs react as there are wolves about, in the evening especially. And we are still here.’

He tosses this over his shoulder as if it were a casual observation about the weather, but I keep glancing behind me, to see if anything is following us, and I am more anxious to stay close to the sled.

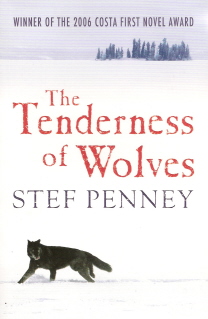

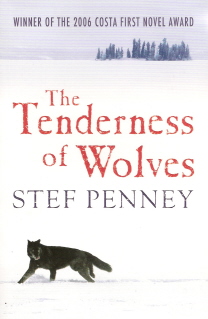

The Tenderness of Wolves by Stef Penney is set in Canada in 1867. It caused a minor stir when it won the 2006 Costa first novel award after it was revealed that its author had never visited the country. All her research was conducted at the British Library. Reading The Tenderness of Wolves I often wished I hadn’t known this; there’s a tendency to overlook many of the novel’s qualities in trying to spot flaws in Penney’s authenticity. So a word of advice if you haven’t yet read the book – don’t embark on an authenticity audit. Penney has never visited Canada, but she’s also never been to 1867, and who was it who said that the past is a foreign country?

I must admit that it took me a long time to settle into The Tenderness of Wolves. It’s a subtle piece of work that portrayed 1867 Canada convincingly to me as a sparsely populated country yet to find a real identity, with settlers from different parts of the world living alongside the native American Indians. It’s a perfect setting for Penney to explore physical and spiritual isolation, with some characters forcing themselves into the inhospitable and bleak winter landscape in bids of escape or missions of discovery, while others remain trapped in remote outposts, succumbing to addiction and madness. It takes commitment to persevere with and fully appreciate this novel, but it’s effort with a very rewarding outcome.

I’m not going to go too deeply into the plot of The Tenderness of Wolves. A man is murdered. Another is suspected. The suspect, his accusers and his defenders all embark on their own personal journeys to find the truth. There is also a background story; two girls disappeared several years previously and, despite extensive searches, were never found. As searches and discoveries take place, the harsh weather always lurks menacingly in the background, along with the wolves who may or may not be watching and circling in the distance. The novel also acts as a lament for the past, personified by the history and integrity of the American Indian, already fading at the time of the book’s setting.

There are a wealth of intriguing characters who, although they don’t immediately jump off the page, develop into complex and believable people. Donald Moody, the young officer thrown into the deep end of the Jammet murder case; Mrs Ross, haunted by her disturbing spell in an asylum; Francis, still only seventeen but already troubled by his memories; the enigmatic Stewart; the mysterious Mr Parker; the pathetically sad Nesbit and Mr Sturrock, a man with an intriguing mystery of his own to solve. There are many others too numerous to mention in this richly populated story.

The Tenderness of Wolves isn’t perfect. Penney is over-reliant on coincidence, and some of the threads in the novel are left unresolved. Mrs Ross, although fascinating, remains ambiguous and puzzling, and the reasons for Jammet’s murder are ultimately ungratifying. I’m not giving away any spoilers; decide for yourself if you’re satisfied with the overall resolution – I’m willing to overlook my slight disappointments.

The Costa success no doubt boosted the reputation of this novel, but I’m always pleasantly surprised when I read such a well crafted and intelligent book in the bestseller lists, albeit one that’s far superior in tone, character and atmosphere than it is in plot. It made me think of the past, our memories and the people we have to interact with – things, at times, that are all foreign countries. Recommended.

Previous Page |

Next Page