Tales That Witness Madness

In 1973 the horror anthology was all the rage. This was mainly thanks to the efforts of Amicus, the main rival to Hammer Films in the 60s and 70s, who churned out their series of portmanteau horrors. With titles like Dr Terrors House of Horrors, From Beyond the Grave and Vault of Horror, the films would each typically contain four of five different chilling tales and feature a host of familiar faces including horror stalwarts Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. The stories would usually be linked together with an often very loose framing device.

In Dr Terrors House of Horrors a fortune teller (Cushing) reveals the fate of fellow travellers on a train (who include, in a bizarre casting experiment, the late disc jockey Alan Freeman). Torture Garden does something similar in a funfair, while Vault of Horror has its subjects recount their disturbing dreams. There’s a great sequence with Terry-Thomas as an over fastidious husband who gets a rather nasty comeuppance. The creepy Asylum visits the tortured worlds of inmates in an institution, while The House That Dripped Blood suitably haunts all of its occupants. All deserve articles in their own right. And I promise that they will come.

Tales That Witness Madness is often mistakenly credited as an Amicus film, although it was actually made by the Rank Organisation. It’s an easy mistake to make. The director is Freddie Francis, who made many films for both Hammer and Amicus, and the cast includes Donald Pleasence, Jack Hawkins and Joan Collins, who were no strangers to this sort of thing. Like Asylum, it uses the framing device of the secure hospital, where a white-coated, bearded and manic eyed Pleasence is running the show. Jack Hawkins, rather foolishly, turns up for a tour of the cells.

Much of Tales That Witness Madness is poor quality. Hawkins, very ill at the time, has his voice dubbed awkwardly by another actor, Charles Gray. The final story is far too long, but there is a moody and memorable opening title sequence and Pleasence is as excellent as you would expect. And, like every British film made in the early 70s, there’s something that makes this essential viewing. Two of the stories, for different reasons, are very good indeed. Mr Tiger concerns a small boy, isolated from the world by his parents who choose to have him educated at home by a private tutor. He invents a furry imaginary friend – or does he? There’s no points for guessing how wrong things go here, and it helps that Rank stretches the budget to employ a real tiger.

The other memorable sequence features Michael Jayston and Joan Collins. Beginning with the eerily memorable line “does anyone here love me?”, this is the most bizarre thing Collins has ever appeared in. This in itself is an achievement from the actress who starred in the insane I Don’t Want to be Born and featured in the Tales From the Crypt segment as a murderous housewife pursued by a maniacal Santa Claus.

Jayston plays a man who, and I can find no better words for this, falls in love with a tree. He names it Mel and moves it into the house, much to – and you can’t forgive her for this – the chagrin of his wife Ms Collins. This being a horror film in the Amicus tradition, things eventually work out better for Mel than they do for Joan. And you can kind of justify why Jayston has ended up in a padded cell, although it’s unfortunate that he only has Donald Pleasence to look after him. From my point of view, the softly spoken voice and intense glare would only make me madder…

The Shout

Saturday November 29, 2008

in 70s cinema |

Think of John Hurt before he became the grizzled character actor he is today. Still fairly young looking and playing an essentially weak man in The Shout, the sort of oddball role he excelled at early in his career – for example in 10 Rillington Place. Think also of Alan Bates at his nastiest. Co-starring with Hurt in The Shout he plays an extension of the character he portrayed in the film of Pinter’s The Caretaker years before; confident and dangerous, sharp eyed and deadly serious. Alan Bates and John Hurt together in one of the weirdest films ever made. Is there anything more you could ask for? The Shout is based on a short story by Robert Graves. It was directed in 1978 by Jerzy Skolimowski, and also features performances by Susannah York, Tim Curry and Robert Stephens.

The Shout opens at a cricket match. It’s no ordinary sporting event; this is a match at an asylum, the kind of country set Victorian bedlam that was perhaps still around in Graves’ day. Here it’s difficult to spot the inmates from the keepers. Tim Curry (restrained compared to his most famous role as Frank N.Furter) plays the Graves character, asked to keep score. He’s joined by an unsettlingly enigmatic man called Crossley (Bates) who elects to tell him a story as the match gets going….

Anthony and Rachel (Hurt and York) live in Devon, the former a church organist who also makes his own recordings at home. It’s a solitary pursuit as his recordings are decidedly odd – the sound of wasps trapped in glasses for example. All looks slightly removed from domestic harmony as Anthony appears to be carrying out a casual affair with the local cobbler’s wife. Coincidentally, Anthony and Rachel both appear to share the same disturbing dream whilst sunbathing on the sand dunes. They both wake suddenly to discover that Rachel has mysteriously lost the buckle of her shoe.

Anthony later encounters Crossley, dishevelled and apparently down and out, who claims not to have eaten for two days during his recent “travels”. He offers him food, and Crossley accepts, with the result becoming not the most pleasurable of lunch dates. Crossley aggrees to no more than a couple of thin slithers of meat. He reveals that he lived in a remote part of Australia for many years, acts generally weirdly and upsets Rachel to the point where she flees the kitchen. Anthony appears to weakly accept the anti-social behaviour and allows him to stay, looking only more and more disturbed as Crossley’s behaviour gets odder. He finds him sitting, naked, in the spare room and quietly boasting that he has perfected the shout, where all who hear it will die…

Now I don’t know about you, but at this point I’d be thinking about showing the man the door. Even calling the orderlies in white coats and possibly arranging a cricket match but certainly not, as Anthony agrees, to witness one of the shouts in person. Early the next day, Anthony follows Crossley to the beach. As a precautionary measure, he plugs his ears, which is a wise move as the shout kills several sheep, their shepherd and other nearby birds on the beach. This really is the stuff of nightmares.

The Shout is a difficult yet compelling film. Alan Bates is remarkable, creating one of the most effective cinema villains I’ve ever seen. This makes it all the more gripping as the puzzled Anthony tries to resolve the situation, especially when Crossley appears to cast a weird charm over Rachel and seduces her. The scenes are all very intense and quietly played out, which makes the release of the pent up energy in Crossley’s shout all the more disturbing. And this is a film that demands repeated viewing.

An extra on my DVD is a commentary by horror experts Kim Newman and Stephen Jones. The Shout isn’t really a horror film, it’s more an exploration of a battle between two men than might be something catastrophic, or might be just a game of cricket. I haven’t listened to all of the commentary yet but it’s very interesting. Nic Roeg turned down the film when he was offered it. Possibly he was too busy preparing Bad Timing. And David Bowie turned down the offer to provide the music, perhaps busy (and foolishly) filming Just a Gigolo. Instead Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford from Genesis took it on, and do a fair job – although this is a film about sound that doesn’t really need a soundtrack. And look out for Jim Broadbent in an early role – pulling the stops out as the cricket descends into mayhem…

Christopher Petit’s Radio On was made in 1979 and has achieved status as a cult, and extremely obscure, British road movie. Filmed in black and white and featuring a soundtrack including David Bowie and Kraftwerk, it’s a moody and experimental piece that offers a fascinating snapshot of England at the end of that troubled decade.

Radio On has escaped my clutches until now, so thanks to the BFI for finally releasing it on DVD. I’ve been interested in catching up with this film for what seems like an eternity; for its acclaimed soundtrack and the use of the twin locations of London and Bristol, my two home towns. The film is probably most well known for featuring Sting in an early acting role, although don’t let that put you off – his performance is far superior to the one in his other 1979 film, Quadrophenia.

Hearing of his brother’s death, a man called Robert (David Beames) embarks on a journey from London to Bristol in his unreliable Rover, encountering several odd characters on his way. A disturbed army deserter (who he wisely ditches by the roadside), a petrol pump attendant (Sting) living in his caravan shrine to Eddie Cochran (who, by no coincidence, died in a motorbike accident on the A4 where Radio On is mostly set), and a mysterious German woman looking for her daughter. Throughout the film Robert appears unable to communicate with others, left in his own thoughts he descends into a drunken spree that leaves him – literally – on the edge.

The snow covered landscape of the South West roads with their seedy filling stations and grimy cafés appears very far removed from the pristine Marks and Spencer Motos of today. Petit’s world is almost an alien one, both from the almost bygone era it represents and for the fact that it is so unlike any other British film of the period. The monochrome shots of the Westway tower blocks look distant and almost East European, and the director does like to dwell on this. There’s also the Kraftwerk tracks and Bowie screaming Heroes in German, and the suggestion that the brother has died as a result of involvement with a European porn ring. But this is no Get Carter. Robert isn’t out for revenge, he isn’t sure what he’s out for at all and the film asks more than it answers. In this way it’s extremely demanding, and what at first appears inconsequential turns out to be a deeply thought provoking look at people stranded in a tired and wasted landscape. As a period piece that looks at Britain on the edge of Thatcherism it’s as good as, if not better, than Stephen Frears’ Bloody Kids.

Yes, there’s an undeniable strange taste to much of Radio On, but it really is a work of art; and the soundtrack is so memorable because it sits so oddly with the film’s content. During the opening scene a camera roams nervously round an empty flat to the accompaniment of Bowie’s Heroes, eventually settling on an apparently dead body in a bath. Workers on a factory shop floor listen to Ian Dury’s Sweet Gene Vincent in a scene that out-weirds David Lynch. Robert lurches drunkenly in a bar to the background of Lucky Number by Lene Lovich and there’s a stunning driving scene to my favourite Bowie song, Always Crashing in the Same Car. Not everyone admires the strange beauty of the Westway or the M4, but you’ll certainly see it in this film. It’s beautifully shot and very, very strange – but well worth a look.

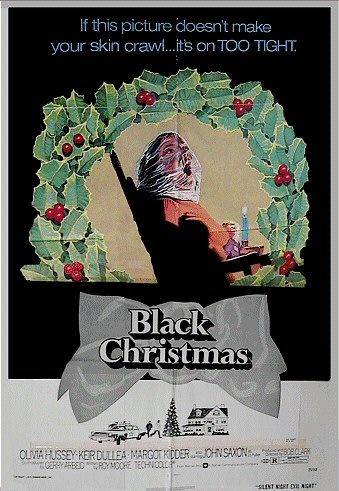

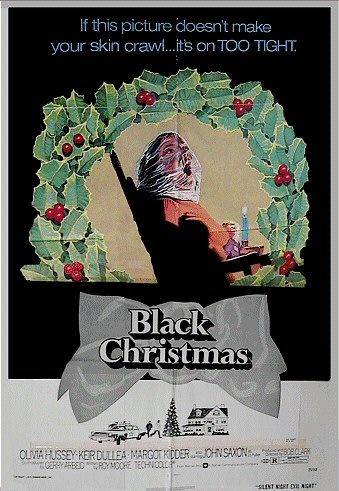

Made in 1974, Black Christmas is a particularly nasty US horror. Coming a few years before Halloween, it looks like John Carpenter made copious notes after seeing this film before he went on to make his better known classic. Many of Halloween‘s most remembered themes turn up in Black Christmas. The seemingly safe sleepy neighbourhood, the ruthless maniac, the college kids who get more than they bargained for, inept police officers, the disturbingly open ending – this film appears to set the blueprint for every horror that’s followed since the mid 70s.

Black Christmas was shown recently on Film 4, but it’s unlikely you’ll see it on any of the more mainstrean channels. It’s a little too blood curdling and there’s strong language that’s still shocking today. A young girl is terrorised by nuisance phone calls. The police attempt to trace them, telling her to keep the menace talking for as long as she can while an expert chases around the local telephone exchange trying to discover where they are coming from. They eventually find out – the calls are coming from inside the house and the madman is revealed to be camping out in the attic. (Incidentally, a plot stolen by a later and another better remembered film called When a Stranger Calls).

Unlike Halloween, there’s no comfort in the fact that the monster might be something supernatural and unworldly – something that isn’t really out there. Black Christmas features a very real and ultimately more disturbing killer. The bogeyman is there alright. Worth catching for horror completists, and to see Margot Kidder in a pre Superman role. The film was remade in 2006 (as was When a Stranger Calls), but the remake disappeared without trace. Accept no imitations.

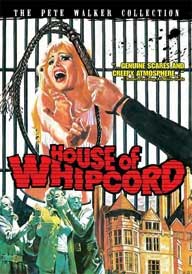

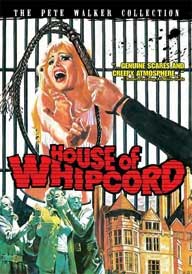

As somebody who has spent a lot of idle time watching most horror film of the 60s and 70s, House of Whipcord has always passed me by. Made in 1974, it’s such an obscure film that I don’t recall it ever being shown on UK television. It took a recent bout of ‘flu and Amazon DVD rental to get it to fall into my hands.

I suspect that one of the reasons that House of Whipcord hasn’t been seen much on television is because at times it is laughably so low budget. Directed by Pete Walker, who also directed Tiffany Jones – the film based on a Daily Mail cartoon – the cast is full of unknown, and particularly weak, actors. The only faces I recognised were Celia Imrie, usually starring with Victoria Wood, and Ray Brooks, most recently seen as Pauline Fowler’s husband (and murderer) in Eastenders. The film features the amount of mild nudity you would expect in a British “X” film of the early 70s, but unlike the lavish Hammer costume dramas of that era, House of Whipcord appears to be filmed on a whipround from Walker’s local pub.

The film concerns a house that has been set up as a private “correction centre”; girls are kidnapped, imprisoned and punished by wardens who could give Prisoner Cell Block H a run for their money. If you don’t tow the line, it’s three shots and you’re out in the House of Whipcord. First punishment is two weeks of solitary in a rat-infested hole, second a serious lashing and it’s curtains for the third. A young French model (Penny Irving) is taken for Correction, with nasty results, although her pretend accent is so absurd that it’s difficult to sympathise with her.

It’s difficult to get through this film; it’s partly hilarious and partly disturbing. You need to shift down into the right gear, and I was crunching the clutch for ages before I found it. Walker’s message is that taking the law into your own hands will lead to crazy results. He still gets that message across. A bit more thought and budget and this could have been a truly great film. Instead, it’s little more than an oddity, but many of the scenes have a chilling and worrying inevitability about them. And it does lend itself to the dare of the best horror films. The main character doesn’t always get away…

Still worth watching for the terrifying Sheila Keith, who appeared in Walker’s other 1974 film Frightmare, Patrick Barr as the decrepid and blind chess-playing judge, and Ray Brooks’ half-hearted acting, totally unconcerned that a friend of his is about to be murdered:

“Excuse me, is there a prison round here, a sort of house of correction?”

“No, sorry”

“Okay, thanks!”

|

Next Page