The other evening, my daughter picked up the copy of The Book Thief by Markus Zusak that I’d left on the kitchen table. I’ve found myself leaving it everywhere, it’s one of those books you can’t help carrying around with you. After examining the cover she asked me two questions. “What’s this book about?” and “who is the skeleton on the cover?”

Well, The Book Thief is about a little girl in Nazi Germany called Liesel. She is seperated from her mother and is fostered by a family who hide a young Jewish man in their basement, but more of him later. Liesel has a habit of stealing books, and stories – stolen, invented, overheard and untold – are at the centre of this novel. It’s about rash decisions, discovery, loss and the power and limitation of words…

Oh, and the skeleton represents Death, who narrates the whole story. So how do you really explain the horrors of Nazi Germany, a book that’s centred around them and – to boot – one that’s narrated by Death to a young child? The Second World War and the Holocaust are subjects that I try to revisit periodically with my daughter. I find it strange that many of her age group have never even heard of Adolf Hitler. What do you tell them ? How far do you go? But I’m going off topic. What was more difficult for me was explaining why I wanted to read a book – a story – about it all. And what makes what Death has to say so interesting?

I found The Book Thief difficult to get into. Partly because I wasn’t sure of the age group it’s aimed at. I suspect it is for quite a young audience, although this ceased to matter as I became accustomed to the style of the writing. The prose is written very simply but this becomes an asset to the unfolding story, especially as the length is nearly 600 pages. The other reason I was uncomfortable as first was the presence of the Death character, which in some reviews has been criticised. This all-knowing and ironic voice is irritating at first, but again it reveals itself as necessary to the power of the book as it gets going.

Zusak’s embodiment of Death does indeed know exactly what is going to happen; who is going to die and in what circumstances, how stories unfold, the winners and the losers. If you can imagine the events of The Book Thief being catalogued on a set of cards, it’s the great skill of how the cards that are dealt to you that makes the book work. Little teasers are laid in front of the reader in periodic bullet lists, which, although infuriating at first, you do get used to.

The power of words is brought home in several of the book’s scenes, but most effectively it’s with the Jewish fugitive Max Vandenburg’s relationship with Mein Kampf. When he is first introduced to us, ironic circumstances mean that a copy of the book helps to provide his key to escape. Later, in Liesel’s basement, he symbolically paints out Hitler’s words to write his own story on the fresh, clean pages.

Words provide comfort and torment to all in The Book Thief. At times, Max is little more than a ghostly figure in his basement retreat and can only utter a pitiful “sorry” or “thank you”. Similarly, when conscripted into the German army, Liesel’s foster father can barely compose a letter home. But words ease others through their tragedy; Liesel reads her stolen words to others as they shelter in an air raid, she also discovers and reads Max’s hidden notebook when he has gone.

Disappointingly, I was allowed to overcongratulate myself on my discovery of The Book Thief‘s themes before Zusak began to over-egg the pudding. In the closing chapters, he really makes sure that the reader knows that this is a book about words and what they can and cannot do, unfortunately spoiling some of the book’s subtlety. But there are other subtle sketches throughout, such as Liesel’s relationship with her foster father and her fondness for him, and with the mayor’s wife, whose library provides rich pickings for a book thief.

I’d wouldn’t quite rate The Book Thief up there alongside my other favourite recent anti-war novels Birdsong and Atonement, but I might tempt by daughter to pick it up properly in four or five years time. I hope she reads it.

Although I’m keen to read the rest of the Gormenghast trilogy, I’m conscious of this becoming too much of a Titus Blog. So I think it’s time to read a couple of other books before I return to Mervyn Peake.

I highly recommend Titus Groan, however, even though the novel is a touch overlong at 500 pages. What works best in the book is Peake’s skill at conveying a sense of space, not only in the vastness of the castle but in each character’s own sense of perspective. In a memorable chapter, Steerpike stands on the castle roof and surveys all around him in great detail. He can see for miles around and takes time to digest as much as he can of his surroundings. And this is what makes Steerpike such a success; he can see exactly what’s going on, whereas most of the other characters in Titus Groan are blinkered, eccentric or, most chillingly, mad.

Other residents of Gormenghast can only struggle to see what’s happening or predict what is going to happen – Peake always conveys the dependence on natural light and the inevitable gloom and shadows that envelop the castle each day. In another memorable scene, the servant Flay spies, by chance, his enemy the drunken chef Swelter as he rehearses an act of murder. As he secretly peers through the gloomy half light he suddenly realises that the murder is his own.

But enough – I’m saving a full review until I’ve eventually read the whole series. Titus Groan was written in 1946, and Peake followed it in 1950 with the equally lengthy Gormenghast. The last book was published in 1959, the comparitively slim Titus Alone. I’ll hopefully be through them all quite quickly, to provide more half glimpsed visions of murder and madness.

‘Lady Fuchsia! May I join you?’

Behind him she saw something which by contrast with the alien, incalculable figure before her, was close and real. It was something which she understood, something which she could never do without, for it seemed as though it were her own self, her own body, at which she gazed and which lay so intimately upon the skyline. Gormenghast. The long, notched outline of her home. It was now his background. It was a screen of walls and towers pocked with windows. He stood against it, an intruder, imposing himself so vividly, so solidly, against her world, his head overtopping the loftiest of its towers.

Greed, ambition, the desire for self-advancement. Ultimately, evil. In Titus Groan, Steerpike appears to Lady Fuchsia to be larger than the vast castle of Gormenghast, overpowering it and engulfing it, his ambition manifest.

A mere worker in the castle’s kitchen, Steerpike has wormed his way up through the ranks of Gormenghast. Escaping from the sinister servant Flay, he literally climbs his way up to more satisfying heights of the castle and finds himself in Fuchsia’s beloved attic by scaling the ivy growing against a wall. A vertical drop of several hundred feet doesn’t sway him. From there he befriends the eccentric Doctor Prunesquallor, through him the weird twin sisters of Lord Groan himself. And then he hatches his devilish and Machiavellian plot…

Titus Groan isn’t the fantastic tale I’d anticipated. Greed, ambition, self-advancement. We see it every day.

Well I’ve started Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake. I’m excited by the fact that I really know next to nothing about this book, or the rest of the Gormenghast trilogy. I’m only a few chapters in, but I’m loving it already. In my edition’s introduction, Anthony Burgess describes the writing style as harking back rather than being progressive, and if I understand what he’s getting at I would liken Peake’s style to Dickens. He’s certainly one for describing grotesque and eccentric characters, and Lady Groan comes across as a distant relation of Miss Havisham:

She was propped against several pillows and a black shawl was draped around her shoulders. Her hair, a very dark red colour of great lustre, appeared to have been left suddenly while being woven into a knotted structure on the top of her head. Thick coils fell about her shoulders, or clustered upon the pillows like burning snakes.

And in the context of the weird castle of Groan, she really doesn’t appear strange at all…

Here’s a helping of the gothic, the fantastic and the downright scary. At the Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft is the story of a particularly disastrous expedition to Antarctica. One group of explorers meet a very gruesome end, whilst a second make some very disturbing discoveries.

It certainly is an effectively chilling story. For me, the opening chapters work the best in how they hint at the horror in the frozen wasteland. Think of having to describe John Carpenter’s film The Thing, but not being allowed to go into gory detail, in fact only being allowed to vaguely suggest what has happened to the alien’s victims. Lovecraft cleverly hints at the impending fate of the explorers; their isolation, the nervousness of their dogs, the very vastness of the unwelcoming landscape:

In the whole spectacle there was a persistent, pervasive hint of stupendous secrecy and potential revelation. It was as if these stark, nightmare spires marked the pylons of a frightful gateway into forbidden spheres of dream, and complex gulfs of remote time, space and ultradimensionality. I could not help feeling that there were evil things – mountains of madness whose farther slopes looked out over some accurse ultimate abyss.

At the Mountains of Madness was rejected by the magazine Weird Tales when it was written in 1931. It’s difficult to see why, as weird it certainly is. But conventional, at least for the time, it isn’t. Whilst the opening chapters sit comfortably in the horror/science fiction genre, the later ones veer off into gothic territory when a second group of explorers unwisely decide to look further. Lovecraft paints a very detailed picture of a vast, ancient and seemingly abandoned city; his description is so vivid that I felt I was walking through its claustrophobic caverns. Creepy and disturbing, but not quick-fix horror.

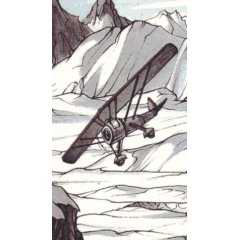

If you haven’t been scared off by the cover art above, it’s from a 1991 edition of the book – described by Amazon as a mass market paperback. You couldn’t find more of a contrast with the cover of a different edition, below, which has more of a connection with the story, showing the foolish explorers travelling into Antarctica by air.

The first cover suggests the quick-fix horror, the second more a Boy’s Own adventure about to go wrong, or a 1930s update of an H. Rider Haggard adventure. A sort of King Solomon’s Mines where no one gets out alive – or sane.

Previous Page |

Next Page