Happy New Year!

- Howards End is on the Landing by Susan Hill 4/5

- Amulet by Roberto Bolano 2/5

- Dead Men’s Boots by Mike Carey (Felix Castor: The Halfway Mark) 2/5

- Legend of a Suicide by David Vann 1/5

- Must You Go? by Antonia Fraser (Must You Go?) 4/5

- The Smoking Diaries by Simon Gray 5/5

- The Ghost by Robert Harris 1/5

- The Unnamed by Joshua Ferris 5/5 (The Unnamed)

- The Year of the Jouncer by Simon Gray 4/5

- Monkey Planet by Pierre Boulle (Monkey Planet) 4/5

- Solar by Ian McEwan 3/5

- The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury (Martian Rock) 5/5

- Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury 4/5

- The Illustrated Man by Ray Bradbury 4/5

- The Cranes That Build the Cranes by Jeremy Dyson (A Double Dyson) 5/5

- The Last Cigarette by Simon Gray 2/5

- What Happens Now by Jeremy Dyson (A Double Dyson) 5/5

- Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head by Rob Chapman (An Irregular Head) 5/5

- The City and the City by China Miéville (City Limits) 5/5

- The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim by Jonathan Coe (The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim) 5/5

- The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell 4/5

- Stories ed. Neil Gaiman and Al Sarrantonio 3/5 (Stories)

- Our Tragic Universe by Scarlett Thomas 2/5

- Tony Hancock: The Definitive Biography by John Fisher 5/5

- Spike and Co by Graham McCann 5/5

- Bounder! The Biography of Terry-Thomas by Graham McCann 5/5

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson 2/5

- C by Tom McCarthy 4/5

- Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon 5/5

- The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene 2/5

- The Girl With Glass Feet by Ali Shaw 1/5

- The Life and Death of Peter Sellers by Roger Lewis 4/5

- The Small Hand by Susan Hill (The Small Hand) 4/5

- Room by Emma Donoghue 1/5

- Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon (kind of…) ?/?

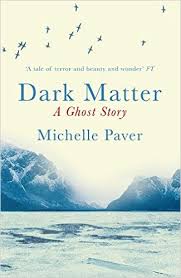

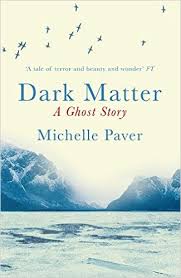

- Dark Matter by Michelle Paver (Endless Night) 5/5

- Life by Keith Richards (Life as we Know it) 4/5

- Under the Dome by Stephen King (Under the Dome 1) 3/5

- The Hopeless Life of Charlie Summers by Paul Torday 4/5

- The Finkler Question by Howard Jacobson 3/5

2010 was an odd reading year. Too many strange choices, too many overlong novels and a few disappointments. However, there were a few highlights, some good and some middling. One or two of my reads were frankly quite awful. I hope the recommendations below are helpful. For what to read and for what to avoid.

Five Star Reviews: Must Reads

Early in 2010 I thoroughly enjoyed The Unnamed by Joshua Ferris, a novel which places him as a major writing talent. I’m very excited about what Mr Ferris has in store for us in the future. The Unnamed is an extraordinary read. I was also highly impressed by The City and the City by China Miéville, a book which has a peculiar knack of easing the reader into the strange world it creates. These two novels are certainly the most original I’ve read for a long time.

Jonathan Coe continued to impress with The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim, a novel which I thought received some unfairly harsh reviews. Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head by Rob Chapman is my music biography choice of the year, which manages to flesh out an oft told, but very sad, life story.

Inherent Vice is Thomas Pynchon’s most accessible novel to date, an amusing tale set during the dying days of 60s California. It put me back in touch with Pynchon, although my attempts to finally finish Gravity’s Rainbow were frustrating.

Ghost stories were aplenty in 2010 although Dark Matter by Michelle Paver was by far the best. A well written, gripping and effectively frightening novel.

Four Star Reviews: Should Reads

Both Howard’s End is on the Landing by Susan Hill and Must You Go? by Antonia Fraser are non fiction choices that I’ll recommend. Fraser’s account of her life with Harold Pinter is very revealing about the man, although any of his admirers looking for critical appraisals of his art should stick with the MIchael Billington biography.

David Mitchell delivered his latest novel The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, although I found it to fall short of the masterpiece I was expecting. But it’s worth sticking this marathon read out. Similarly with C by Tom McCarthy, which was certainly a clever novel but one perhaps a trifle too pleased with itself.

Paul Torday’s latest, The Hopeless Life of Charlie Summers, is my favourite of his to date. Torday has a charming and unique style and this is a very moving tale that’s worth reading.

The Small Hand by Susan Hill and Life by Keith Richards are respectively the second best ghost story and music biography of the year.

The Small Disappointments: You May Want to Avoid

Both Solar by Ian McEwan and Stories ed. Neil Gaiman and Al Sarrantonio failed to deliver. In particular the Gaiman anthology was a wasted opportunity, which featured very few short stories of worth. The best was Sarrantonio’s own offering.

The Big Disappointments: Please Avoid

Legend of a Suicide by David Vann was recommended by several blogging friends but it just didn’t work for me. The Ghost by Robert Harris and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson were tedious doses of popular fiction. Our Tragic Universe by Scarlett Thomas was a dull read and The Girl With Glass Feet by Ali Shaw was pitiful. Girl With… books just don’t work for me. Enough said.

However my worst read of 2010 was Room by Emma Donoghue, the most overrated book for a long time. I found it unconvincing and the narration-from-the-point-of-view-of-a-child irritating. Can somebody please explain why this novel is supposed to be so good?

But enough grumpiness. Here’s to continued enjoyable reading in 2011. Good health!

Russell T.Davies picks Stephen King’s Under the Dome in the Guardian’s Books of the Year 2010. It strange that his choice only appears on the Guardian iPhone app and not the website. Perhaps the paper don’t want to fully endorse such a commercial author. Or Russell T.Davies.

I’ve only read a few hundred pages of Under the Dome, a novel which ranks as one of King’s longest. And most ambitious – he claims to have delayed writing it for years until he matured sufficiently as a writer. It’s easy to understand his caution. A deceptively simple premise (an American town is encased by an invisible yet inpenetrable force field) is handled with great skill to unravel a complex story with a huge cast of characters. The opening chapters, dealing with the consequences from the day when the dome falls, are brilliantly handled and a lesser writer would have failed in setting up the book so brilliantly.

Once King’s outstanding opener has passed the book settles down into character study, carefully sketching out who’s who as the horror of the situation begins to sink in. I’m going to be in for a long ride, although Davies reckons that the last 100 pages of The Dome are the best that King has written, so the journey should be worth it.

What a drag it is getting old.

The Rolling Stones, Mother’s Little Helper

In the mid 1980s, Keith Richards saw the Rolling Stones as doomed. Mick Jagger was entertaining a solo career and turning his back on the band, whilst Richards himself indulged in touring with other musicians – his own band The X-pensive Winos and also appearing with Chuck Berry. Maybe age had caught up on them, and as Jagger and Richards entered their 40s there was a possibility that the Stones’ days were over. But of course it was far from the end, Jagger and Richards resolved their differences and the Rolling Stones pulled together again in 1989 for the first of their mega-tours. As Richards writes in his biography Life, they had another two decades of playing live ahead of them. At least.

Life is one of the most entertaining rock bios I’ve read in a long time. Now 66, Richards still doesn’t want to stop – he’ll play on until he drops. And whilst there are some signs of mellowing with age, he writes with some clarity about the years of hell raising. The heroin and the cold turkey, the endless rounds of getting clean to go on tour only to fall back into the old ways again, and the countless scrapes – drug busts, flashed knives and firearms, fistfights (usually with other band members) and his fractious relationship with Anita Pallenberg. Richards puts his surprising longevity down to pacing himself through the madness and sticking to the purest of drugs – no low quality smack, or Mexican shoe scrapings as he calls it. He doesn’t exactly advocate drugs, but asks us to accept that it was a way of life for him – and one that in some ways appears to have aided his talent (who else would stay up for days and nights at the mixing desk where others fell around him?) But some of it is far from impressive, such as the time he took his seven year son on tour with him when he was at the lowest point of his drug taking. Crazed and sleeping with a loaded gun under his pillow, young Marlon was the only person trusted to wake Richards. It isn’t really funny.

Better, Richards talks at length about the musical influences that shaped his talent, beginning with his upbringing in Dartford. Life portrays the immediate postwar England with great charm and insight, especially with a vivid picture of Kent in the 40s and 50s with the local lunatic asylums and nearby woods full of madmen and army deserts. An only child raised in a matriarchal family, he was bullied at school (his subsequent toughness in the book vividly contrasting with this picture of the weedy pre Stone). Expulsion from Secondary Modern led to art school, an obvious career path for a budding musician in the late 50s, which put him in the right circle for forming the Rolling Stones. As for the band, Keith’s view of Mick Jagger has become the talking point of Life, mainly in how he charts their various long running disputes and checkered partnership, although there isn’t really enough here to stop the pair talking for ever. At the most we can assume that Jagger is somewhat possessive of Richards position in his life, and was also frustrated when Richards cleaned up at the end of the 70s and the position of power changed in the band. Oh, and you may have heard that Keith refers to Mick’s rather small, er, member. Jagger is no doubt smarting at this revelation, but probably not as much as over the vitriol Richards pours on his trilogy of laughable solo albums in the late 80s.

Apart from the love/hate relationship with Jagger, Richards also has a high regard for Charlie Watts, whilst Bill Wyman hardly gets a mention (mostly he finds Wyman’s celebrated womanising laughable) and background band members, such as the keyboard player Ian Stewart receive greater prominence than Bill in the Stones story. Brian Jones is viewed as nothing more than a dead weight, a talented musician subsequently relegated to the sidelines when Mick and Keith are elected by Andrew Loog Oldham as the band’s songwriters. His early death receives less than half a page in this lengthy memoir. Mick Taylor, the guitarist who bridged the gap between Jones and Ronnie Wood, is respected as a musician but found too introverted. Wood himself is acknowledged as a worthy addition to the band, although his own problems with addiction at times put Richards’ own into perspective. Richards also has a high disregard for two of the film makers associated with the Stones, Donald Cammell (who made Performance starring Jagger and Pallenberg) and Jean Luc Godard (responsible for the weird Sympathy for the Devil film). Of his 60s contemporaries, Richards has a high regard for only a few, amongst them John Lennon who, joining in with the indulgences, only ever left his house horizontal.

Co-writer James Fox does a fine job in holding it all together, although things begin to become fragmented slightly towards the end. Keith goes into his recipe for sausages at length but barely mentions his Pirates of the Caribbean acting role. However he does prove that’s he’s still no stranger to the headlines, recounting both his near fatal head injury of recent years and the tabloid sensation that he snorted his father’s ashes.

Settling the score on gossip aside, readers interested mostly in the Stones back catalogue will find that the most discussed album here by far is the celebrated Exile on Main Street. Lesser known albums, such as 1967’s Between the Buttons, receive no mention at all, whilst Richards dismisses Their Satanic Majesties Request as weak. Life gives some insight into the effort that went into their better albums, and the less musically inclined reader will, like me, become lost with the lengthy account of how Richards re tuned his guitar to achieve a distinct sound. But listening to some of the albums afresh, including Beggar’s Banquet, Let in Bleed and Exile, I’m convinced by his greatness as a musician far more than I’ve ever been before. And even though I don’t know the technical ins and outs, I certainly do know a track such like Satisfaction is unbeatable.

So to wind up, here’s a rundown of the Rolling Stones at their best:

- Under my Thumb (Aftermath 1966)

- Sympathy for the Devil (Beggars Banquet 1968)

- Jig-Saw Puzzle (Beggars Banquet 1968)

- Street Fighting Man (Beggars Banquet 1968)

- Gimme Shelter (Let it Bleed 1969)

- You Can’t Always Get What you Want (Let it Bleed 1969)

- Rocks Off (Exile on Main Street 1972)

- Tumbling Dice (Exile on Main Street 1972)

- Happy (Exile on Main Street 1972)

- Shine a Light (Exile on Main Street 1972)

At that moment, I sensed I was not alone.

Would you like to be scared? I think I have the solution. Dark Matter is an intriguing ghost story and one perfect for the run up to Halloween. Michelle Paver weaves a delightfully spooky tale with a 1930s Arctic setting, the background of intense cold and lack of daylight very fitting for a story dealing with loneliness, paranoia and fear.

Would you like to be scared? I think I have the solution. Dark Matter is an intriguing ghost story and one perfect for the run up to Halloween. Michelle Paver weaves a delightfully spooky tale with a 1930s Arctic setting, the background of intense cold and lack of daylight very fitting for a story dealing with loneliness, paranoia and fear.

Dark Matter takes the form of the journal of Jack Miller as he joins an ill fated expedition to the remote bay of Gruhuken. He’s an edgy young man, conscious of the class distinction between himself and his fellow adventurers, and at first finding himself unable to establish any affinity with them. Paver plays on this well, with Jack picking up on the slightest tension which sets the reader up for what’s to come, where an overactive mind is left to work a touch overtime.

At first it all appears to be familiar territory of the ghost story. The expedition charters a boat and the Captain is reluctant to take them all of the way; there’s something unspeakable that happened at Gruhuken. Eventually arriving, the crew try to dissuade them from tearing down the encampment of previous settlers. There’s a distinct aroma of folklore and superstition. In the midst of this Jack thinks he has encountered a ghost, and whilst reasoning that a ghostly apparition can only frighten and not harm, he struggles to keep his thoughts rational.

Paver is successful in making this a gripping story in how Jack’s narrative is so convincing. She’s visited the Arctic herself, and so the description of it is rich, varied and believable. But what’s most arresting is that no matter how Jack attempts to rationalise events the reader can taste his increasing fear, and fear in a narrator works extremely well in stirring the same in the reader. A series of problems leaves Jack alone at the camp, where he attempts he attempts to keep isolation at bay by following a strict regime, exercising himself in the bitter darkness and attending to his dogs, his only living companions. But the rot of fear sets in, and he begins to succumb to his imaginings and compulsive desire to look out of the window…

This is an engaging and scary novel that’s highly recommended.

Previous Page |

Would you like to be scared? I think I have the solution. Dark Matter is an intriguing ghost story and one perfect for the run up to Halloween. Michelle Paver weaves a delightfully spooky tale with a 1930s Arctic setting, the background of intense cold and lack of daylight very fitting for a story dealing with loneliness, paranoia and fear.

Would you like to be scared? I think I have the solution. Dark Matter is an intriguing ghost story and one perfect for the run up to Halloween. Michelle Paver weaves a delightfully spooky tale with a 1930s Arctic setting, the background of intense cold and lack of daylight very fitting for a story dealing with loneliness, paranoia and fear.