Night Must Fall

Saturday October 29, 2016 in halloween | 60s cinema

The first of two halloween posts this year.

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

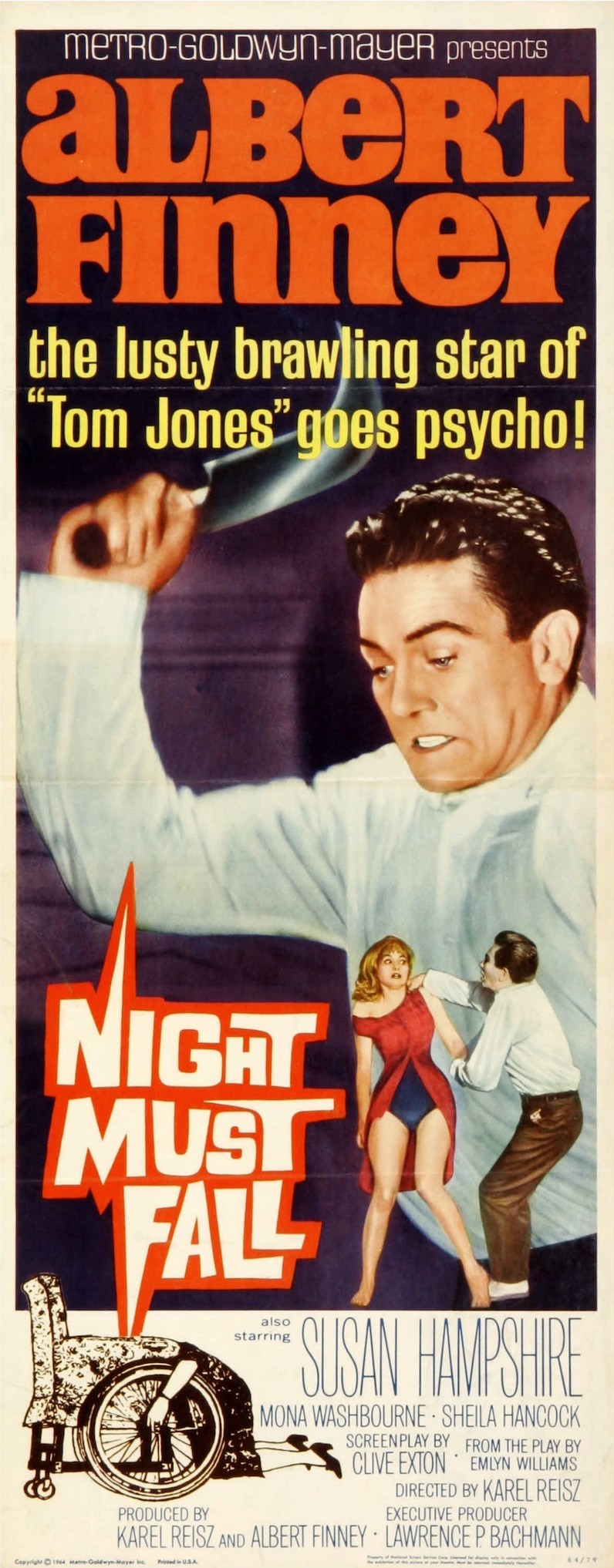

The tag line for many of Night Must Fall’s original posters reads “the lusty bawling star of Tom Jones goes psycho”, so while audiences weren’t allowed to forget Finney’s most recent success, they were also enticed into seeing the new movie idol in a more controversial role. Hitchcock’s Psycho obviously still very much in the public consciousness at the time, the film’s marketing must have suggested that Finney was exploring Norman Bates territory.

If Wikipedia is anything to go by, Finney was one of the top ten box office stars at the time, so this film was a bold move for the actor who turned down Lawrence of Arabia. But unfortunately Night Must Fall was not a success and is mostly forgotten, perhaps the least remembered film of an actor who starred in comparatively few films anyway (indeed, Night Must Fall was only his fourth film and he chose to give the cinema a rest for three years after this, returning in 1967 with the equally odd Charlie Bubbles).

Night Must Fall is a remake of an even lesser known 1937 film of the same name, which was in turn based on the 1935 play by Emlyn Williams. With Reisz directing from a script by Clive Exton (who also wrote the screenplay for 10 Rillington Place) and with Finney as producer, it also stars Mona Washbourne, Susan Hampshire and Sheila Hancock. The film was entered into the 14th Berlin International Film Festival. The excellent black and white cinematography is by Freddie Francis, and whilst some of the acting is decidedly (and deliberately) offbeat, if you can find a good print of the film it looks amazing.

Finney is the centrepiece as Danny, an odd young man who charms his way into the house of an apparent invalid Mrs Bramson (Washbourne) and her daughter Olivia (Hampshire) via his girlfriend, their housekeeper Dora (Hancock). Affecting a Welsh accent, Finney is determined to pull out all of the acting stops from the beginning and succeeds in delivering quite a mesmerising performance. He makes it no secret he’s unhinged, and there’s no secret either that the brutal murder that forms the backdrop of the story is his responsibility. Going back to the Psycho comparisons, little is shown in terms of violence or bloodbath and brutal murder wise most is left to the imagination. Worming his way into her affections, Mrs Bramson allows Danny to call her “mother”, which leads to her downfall. So also, like Bates, Danny does appear to have parental issues that have led to his outlook on life, although it’s much more subtle here. And there’s many a quietly handled and telling scene; watch out for the “puzzle hand”.

Thinking about Night Must Fall and the period it was made, I’m inclined to place it somewhere between The Servant (1963) and The Collector (1965). The Servant because there are some similarities visually, there is the depiction of weird childish game playing, and the exploration of a class theme (although Danny’s wish to rise a social class is less explicit than Dirk Bogarde’s Barrett). The Collector because it was another film with American backing that placed a young British star (Terence Stamp) in a very peculiar and shockingly non-starry role. The Collector is a better and more convincing film in my view (and it also features Mona Washbourne) but Night Must Fall is still essential viewing.

Karel Reisz went on to direct Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment in 1966 which (along with Saturday Night and Sunday Morning) is a far more celebrated 60s film. Looking through Finney’s subsequent roles, I can’t really see anything he did that stands out in a way that Danny does. I’m willing to be challenged on this, but mostly he seems to have succeeded in his wish not to be pinned down in any way after his early success, moving between musical (Scrooge in 1970), detective (as the original Poirot in 1974’s Murder on the Orient Express) and horror (Wolfen in 1980) genres. And most recently James Bond: he’s the best thing in 2012’s otherwise dire Skyfall.