What use would a woman’s blood be to the soil? It needs a man.

What if there was a precursor to such rural British horrors as The Wicker Man, Eden Lake and Sightseers ?

Robin Redbreast was broadcast as a BBC Play for Today in December 1970. Due to a power cut that evening, many viewers missed the full transmission and so it was rebroadcast a few months later. This was the first time a Play for Today had ever earned a repeat showing. It hasn’t been shown since however, and the recent DVD release only features a surviving black and white copy. Writer John Bowen was also responsible for the Ghost Story for Christmas in 1978 The Ice House.

Script editor Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) leaves her friends in London, Jake (Julian Holloway) and Madge (Amanda Walker), seeking for “clearer thought” and rents a cottage in a remote rural area of southern England. Jake and Madge are sceptical of her departure – perhaps she’ll take to drink out there all alone (although they are never seen without a wine glass in hand)

Script editor Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) leaves her friends in London, Jake (Julian Holloway) and Madge (Amanda Walker), seeking for “clearer thought” and rents a cottage in a remote rural area of southern England. Jake and Madge are sceptical of her departure – perhaps she’ll take to drink out there all alone (although they are never seen without a wine glass in hand)

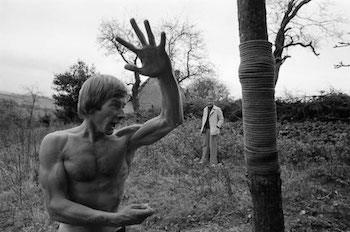

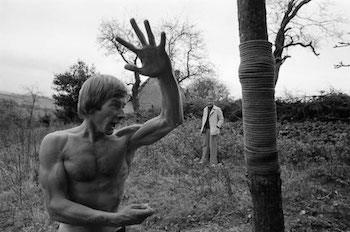

Norah quickly meets a series of odd characters: Mrs Vigo, her intimidating housekeeper; Mr Fisher (Bernard hepton), a local amateur archaeologist; Rob a young man who practices karate in his underpants the woods; Mr Wellbeloved, the butcher; Peter an old man, constantly chopping wood. An eye-shaped marble is placed outside her window.

During the night a bird is put down the chimney into the cottage and Rob comes to Nora’s rescue. She allows him to seduce her, despite finding her contraceptive cap missing. She falls pregnant and the villagers contrive that she does not leave before Easter. Her car will not start, buses will not stop for her, and phone calls are cut off at the “exchange”.

Rob returns to discuss it all. They realise villagers surround the house and an eye appears at the keyhole. Two villagers enter, including Peter with his axe and Nora faints. She does not hear Rob’s screams. She awakes to find Mrs Vigo and Mr Fisher in the house. She is told that Rob has left to go to Canada.

Mr Fisher explains the cultural importance of the name Robin in British folklore: Robin Hood, Robin redbreast etc. We have already been told that Rob had been called “Robin” only by the villagers, and his real name was Edgar. He has played a sacrificial role, and will be replaced by a new “Robin”…

Robin Redbreast has a very matter of fact strangeness about it, helped by the lack of any soundtrack music. Bernard Hepton is superb as Fisher, a man you wouldn’t really want to let into your home. Cropper is pretty good too, and also worth looking for is the 1972 Dead of Night episode she appeared in called The Exorcism.

During the recent site redesign and reshuffle (like it?) I came across an unfinished post from last year. It was a sequel to 2008’s Oddball Films. As I’ve managed to catch up on many of the obscure titles discussed at the time I’ve decided to update it.

Seen and Reviewed

Discussed at length in the following articles:

The Blockhouse

Tales that Witness Madness

The Mind of Mr Soames

Danger: Diabolik

Discussed here:

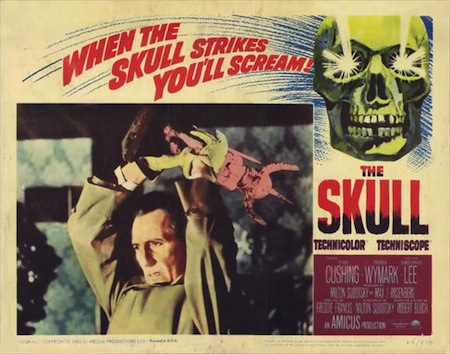

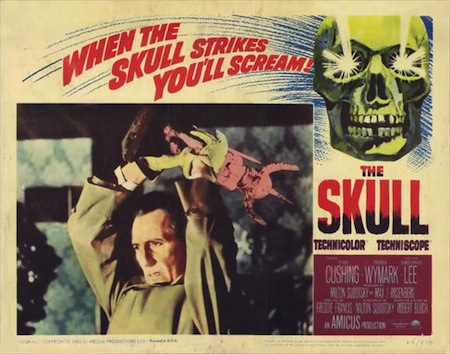

The Skull (1965)

Made by Amicus in 1965, The Skull is an effective film charting the horrific consequences for those who come into the possession of the skull of the Marquis de Sade. Directed by Freddie Francis, it stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee with a great supporting cast including Patrick Wymark, Jill Bennett, Patrick Magee, Peter Woodthorpe and Michael Gough. Cushing is outstanding as always, particularly in an effective dream sequence where he is forced to play Russian Roulette. Wymark is also good as a seedy dealer in horrific artifacts. The Skull is based on a story by Robert Bloch, who was responsible for Psycho.

The Skull makes interesting viewing thanks to the direction of Francis, who shoots the majority of scenes in claustrophobic interiors. The last half hour of the film is also entirely without dialogue. But what’s most disturbing is that the real life skull of the Marquis de Sade is still missing…

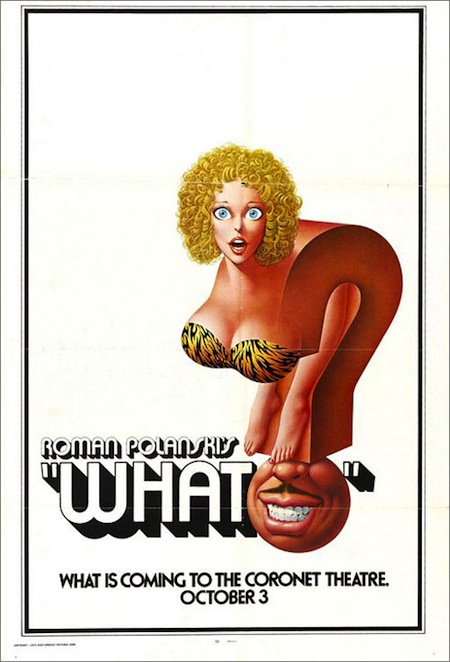

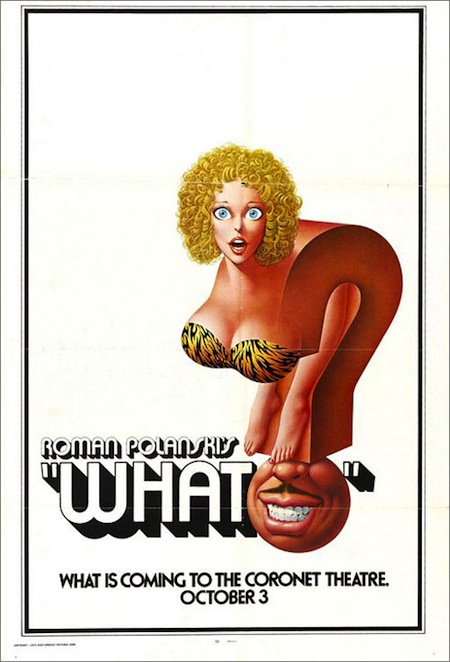

What? (1972)

Also known as Che?, this is possibly the most obscure film from Roman Polanski’s career (not including A Day at the Beach, which I’ll be discussing soon). What? is a strange sex comedy that doesn’t quite hit the mark, although it’s interesting for featuring the director in an acting role (wearing a strange moustache and a black eye). The film also has a typical Polanski setting in a villa by the sea. This is almost Cul-de-Sac territory, and there are even some similarities with the remote locations of The Ghost. Worth seeing, if only an appearance by the brilliant Hugh Griffith. And What? is still miles better than The Ghost.

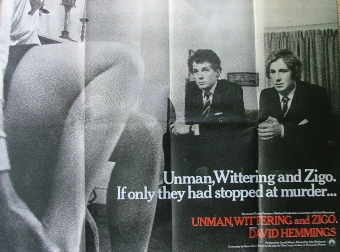

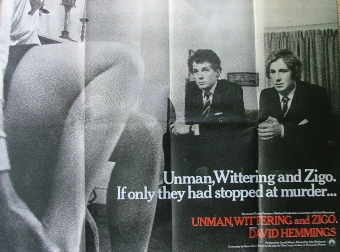

Unman, Wittering and Zigo (1971)

This film starring David Hemmings was based on a 1950s radio play by Giles Cooper. Hemmings is superb as new schoolmaster John Ebony in a boys’ school, slowing waking up to the mystery of the missing Zigo of the title. Director John Mackenzie (who later made The Long Good Friday) conveys a slow burning sense of tension as Ebony begins to lose control of things.

This film starring David Hemmings was based on a 1950s radio play by Giles Cooper. Hemmings is superb as new schoolmaster John Ebony in a boys’ school, slowing waking up to the mystery of the missing Zigo of the title. Director John Mackenzie (who later made The Long Good Friday) conveys a slow burning sense of tension as Ebony begins to lose control of things.

A very rewarding film, although the version available on YouTube is of poor quality. Carolyn Seymour (from the original Survivors) is impressive as Ebony’s wife, and look out for the young Michaels Cashman and Kitchen.

In 1974 Peter Sellers revived his flagging film career by agreeing to resume the role of Inspector Clouseau. The Pink Panther franchise produced a run of successful films up until his death in 1980. It’s an odd coincidence that in the year before his “comeback” Sellers played another Frenchman in possibly the most obscure film he ever appeared in. The Blockhouse is not a starring vehicle for him, but rather an ensemble piece where he plays one of seven men trapped in an underground bunker during World War II. The unusual cast also includes Charles Aznavore, Leon Lissek, Jeremy Kemp and Peter Vaughan. It’s a rare straight role for Peter Sellers.

The Blockhouse is directed by Clive Rees and based on a novel by Jean Paul Clebert, which in turn is supposedly based on real life events. If this is true then it is an extraordinary story. The seven men, all prisoners of war, are trapped underground during the D-Day raids. They find themselves in a German “blockhouse”, an underground shelter with food, drink and – equally importantly – candles to keep them alive for years. And it turns into years. In 1951, so the story goes, two men were rescued from a blockhouse after surviving for seven years, four of them in total darkness.

The Blockhouse is directed by Clive Rees and based on a novel by Jean Paul Clebert, which in turn is supposedly based on real life events. If this is true then it is an extraordinary story. The seven men, all prisoners of war, are trapped underground during the D-Day raids. They find themselves in a German “blockhouse”, an underground shelter with food, drink and – equally importantly – candles to keep them alive for years. And it turns into years. In 1951, so the story goes, two men were rescued from a blockhouse after surviving for seven years, four of them in total darkness.

Thus The Blockhouse is fairly depressing subject matter, although it is compelling viewing due to the excellent performances. Especially Sellers. Despite the megalomaniac he is often portrayed of in biographies, he does not attempt to steal the limelight in this film any way. A truly brilliant performer, who sadly squandered his talent on often substandard material. Peter Vaughan, another actor better known for comedy, is also very impressive as the first to crack under the strain (a piece of trivia: Vaughan also played Sellers’ father in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers). Unfortunately the film quality of The Blockhouse is poor, with the direction uneven. It’s no surprise that Rees did little else. But there are several memorable sequences. Sellers attempting to teach his fellow captives dominoes, an ill-advised bicycle race, and Sellers (again) resolved to his final moments under the earth. This, together with the final scene when the supply of candles comes to an end, is very moving.

It’s strange that The Blockhouse fell into obscurity for so long, and there’s probably a metaphor there somewhere to compare the film with the plight of the seven forgotten men. I’m not aware of it ever being on UK television. Stranger still, it is now available as part of The Peter Sellers Collection on DVD together with Where Does it Hurt? and Orders are Orders, arguably his two other least known films. I would think any Pink Panther fans buying this will be in for a shock.

When Kim Newman recommends something I usually sit up and listen. The avuncular film critic and horror fan has recently released his Guide to the Flipside of British Cinema, a 40 minute documentary that accompanies the BFI’s series of obscure British movies now available on DVD. The films date from the 1960s and as a dedicated fan of forgotten cinema I have to confess that I’ve only ever seen two of them. Richard Lester’s The Bed Sitting Room (1969) is easily the best known of the collection, and even though I’ve never been a big fan of the film, Newman promises a fully restored print. Also there’s Privilege (1967), Peter Watkins study of pop stardom which followed his controversial television works Culloden and The War Game.

But it’s the films that have so far escaped my attention that interest me the most:

But it’s the films that have so far escaped my attention that interest me the most:

- Man of Violence (1968), a result of Pete Walker’s brief flirtation with the crime genre.

- All the Right Noises (1968), starring Tom Bell and Olivia Hussey.

- Herostratus (1967), which looks like the most pretentious art film ever conceived. Mr Newman, however, assures us that it is well worth watching. And this is a must as far as I’m concerned as it features an early film appearance by Helen Mirren.

- Primitive London (1965), a shocking doumentary on the seedier side of the capital.

Newman’s DVD is nothing more than a taster for these films, so expect nothing more sophisticated than a series of clips and shots of him discussing them. Oddly, he doesn’t mention all of the films available in the Flipside series, missing out Guy Hamilton’s The Party’s Over featuring a young Oliver Reed. It’s on the top of my must-see list. Expect a review shortly.

Kim Newman’s Guide to the Flipside of British Cinema also features three short films. The Spy’s Wife, made in 1972, is a very odd film starring Tom Bell and Dorothy Tutin and directed by Gerry O’Hara. Perfect for spotting London locations but only just manages to stay its 28 minutes welcome. Tomorrow Night in London is a very short piece from the late 60s showcasing the happening scene of the time. It’s the sort of thing repeated on Channel 4 afternoon viewing until about 1990. Carousella is a black and white documentary about strip artists, which brings to mind elderly gentlemen in long raincoats at the Scala Cinema. However it is rather fascinating, and is well worth investigating – the mood reminding of Ken Loach’s Poor Cow.

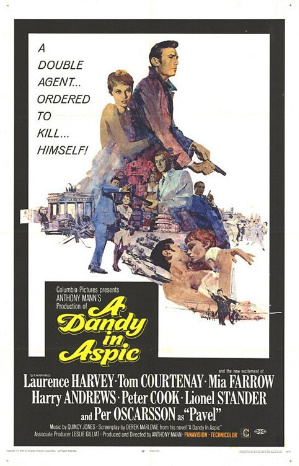

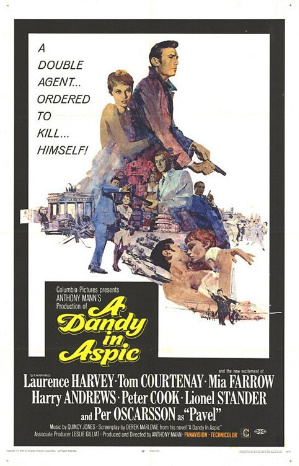

After recently watching Bedazzled on late night tv I decided to seek out the spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic, which features Peter Cook in a cameo role. This 1968 film is set in London and Berlin and stars Laurence Harvey, Mia Farrow and Tom Courtenay. It’s filmed beautifully; London is damp and autumnal whilst Berlin is by contrast sunny and light, but while the cinematography is excellent the direction does owe a debt to The Ipcress File which came a few years before. There’s even a John Barry-eque haunting theme tune (actually by Quincy Jones), so while A Dandy in Aspic is a worthy addition to the cold war film canon, it does little more than tag along to the already set templates of the genre.

Harvey, one of the oddest leading men in film history, is quite wooden in this film. Farrow doesn’t shine particularly either, so it’s really up to the supporting cast to jolly things along. Whilst Courtenay seems misplaced in this movie, there’s excellent turns from Harry Andrews, Geoffrey Bayldon, John Bird (from tv’s Bremner, Bird and Fortune) and Mike Pratt (Randall in Randall and Hopkirk, Deceased). Also worth mentioning is Norman Bird, the supporting actor who appeared in countless British films in the sixties. Any casual student of this period in cinema will probably say oh, him again, whilst the posher critic might even say ah, the ubiquitous Norman Bird. But I always feel in safe hands when I spot Norman Bird. Then of course there’s Peter Cook, and although he only really has a tiny role he’s very good in it and it’s odd to see him in a rare serious acting role.

The cold war spy plot of A Dandy in Aspic is as complex and convoluted as the similarly themed Funeral in Berlin or The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. It’s been unjustly forgotten though, and it’s genuinely thrilling, although a touch deliberately confusing. Harvey plays a Russian double agent, coerced into travelling from London to East Berlin in order to carry out an assassination. There’s bluffs and double bluffs, and any attempt to further flesh out the storyline becomes bogged down with too many or is he? s and but did he? s. There’s also an interesting parallel with The Prisoner, where the but is he? s and an and does he? s also come into play.

The film’s director Anthony Mann died in Berlin in 1967 before filming was completed. Harvey picked up the pieces and finished A Dandy in Aspic, and while you can’t really see the joins this serious hiccup to production is obviously why this is an often erratic and bewildering film. For a decent spy thriller, your time is better spent with Michael Caine as Harry Palmer, and if it’s a mysterious, cerebral and absorbing sixties film then try The Quiller Memorandum. Now there’s a really good John Barry soundtrack. But A Dandy in Apsic is worth seeking out, especially for Peter Cook and Norman Bird completists like me.

Previous Page |

Script editor Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) leaves her friends in London, Jake (Julian Holloway) and Madge (Amanda Walker), seeking for “clearer thought” and rents a cottage in a remote rural area of southern England. Jake and Madge are sceptical of her departure – perhaps she’ll take to drink out there all alone (although they are never seen without a wine glass in hand)

Script editor Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) leaves her friends in London, Jake (Julian Holloway) and Madge (Amanda Walker), seeking for “clearer thought” and rents a cottage in a remote rural area of southern England. Jake and Madge are sceptical of her departure – perhaps she’ll take to drink out there all alone (although they are never seen without a wine glass in hand)

This film starring David Hemmings was based on a 1950s radio play by Giles Cooper. Hemmings is superb as new schoolmaster John Ebony in a boys’ school, slowing waking up to the mystery of the missing Zigo of the title. Director John Mackenzie (who later made The Long Good Friday) conveys a slow burning sense of tension as Ebony begins to lose control of things.

This film starring David Hemmings was based on a 1950s radio play by Giles Cooper. Hemmings is superb as new schoolmaster John Ebony in a boys’ school, slowing waking up to the mystery of the missing Zigo of the title. Director John Mackenzie (who later made The Long Good Friday) conveys a slow burning sense of tension as Ebony begins to lose control of things. The Blockhouse is directed by Clive Rees and based on a novel by Jean Paul Clebert, which in turn is supposedly based on real life events. If this is true then it is an extraordinary story. The seven men, all prisoners of war, are trapped underground during the D-Day raids. They find themselves in a German “blockhouse”, an underground shelter with food, drink and – equally importantly – candles to keep them alive for years. And it turns into years. In 1951, so the story goes, two men were rescued from a blockhouse after surviving for seven years, four of them in total darkness.

The Blockhouse is directed by Clive Rees and based on a novel by Jean Paul Clebert, which in turn is supposedly based on real life events. If this is true then it is an extraordinary story. The seven men, all prisoners of war, are trapped underground during the D-Day raids. They find themselves in a German “blockhouse”, an underground shelter with food, drink and – equally importantly – candles to keep them alive for years. And it turns into years. In 1951, so the story goes, two men were rescued from a blockhouse after surviving for seven years, four of them in total darkness. But it’s the films that have so far escaped my attention that interest me the most:

But it’s the films that have so far escaped my attention that interest me the most: