1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

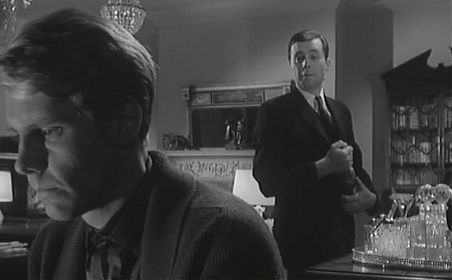

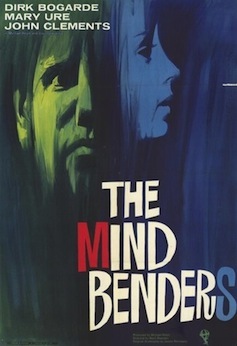

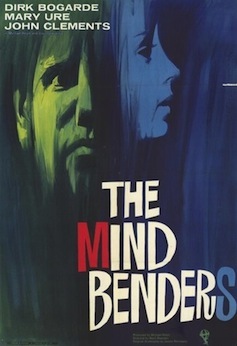

The last of the bunch was The Mind Benders, a film directed by Basil Dearden that has now unjustly dropped into obscurity. Bogarde stars as Dr Henry Longman, a scientist dabbling in experiments in isolation. Although sometimes billed as science fiction or as an early cold war thriller, and the subject matter hints at 60s hallucinogenic cinema, The Mind Benders doesn’t neatly fit into any genre. However it is an absorbing and literate film that’s worth seeking out.

The film opens with Professor Sharpey (Harold Goldblatt) throwing himself from a moving train on route to Oxford University. A large sum of money is found on him and upright Major Hall (John Clements) assumes that the unfortunate don was a traitor, selling secrets to the Russians. Hall goes on to discover that Sharpey was working on isolation experiments with his colleagues Dr Tate (Michael Bryant) and Longman, with Sharpey and Longman actively taking part in the tests. A man born to snoop around, Hall confronts Longman with the suggestion of Sharpey’s treason and an unconvinced Longman talks himself into allowing Hall to witness an isolation experiment. With Longman as the subject…

This is a film devoid of special effects or sensation. However the black and white photography of The Mind Benders helps to enhance the creepy presence of the isolation chamber, a huge water tank where Longman is suspended without light, sound or feeling. Tate and Hall observe him as he passes through several states of consciousness, including confusion, panic and hallucination, in a marathon seven hour session. The chamber is likened to something from Frankenstein and this is how we perceive Longman as he emerges from it – almost a rebirth as he comprehends reality with wide, frightened eyes. And this is one of the great Bogarde performances; at this point we know that he’s really going to get his teeth into the part.

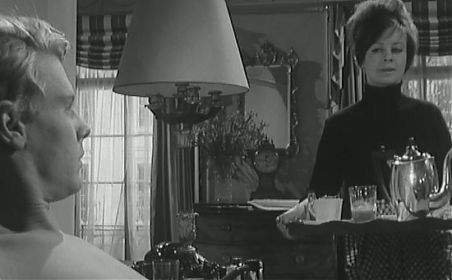

Hall believes that Sharpey was brainwashed, and that a man fresh from the isolation tank is open to interrogation and suggestion. Here lies the crux of the film. He coerces Tate into a further experiment, where they taunt the vulnerable Longman with improper suggestions about his wife Oonagh (Mary Ure). Hall believes, rather naively, that whatever wrong they do to Longman can be undone (a bent mind can be unbent so to speak). And whilst Longman appears to quickly recover from his ordeal and it seems that the brainwashing aspect of the experiment has failed, we know that something is going to be amiss, and the second act begins with Tate visiting the now visibly odd Longman (Bogarde manages to make use of a pair of glasses alone to appear effectively sinister) and the now pregnant Oonagh. The rest of the film plays out with Tate and Longman wresting with their own uncontrollable Frankenstein’s monster in the shape of Bogarde at his nastiest.

The Mind Benders is a very talky film but saved by excellent performances all round. Ure is as good as Bogarde as the unfortunate Oonagh, and Wendy Craig (who also appeared in The Servant) has a supporting role. The ending, which I won’t give away, drives home the theme of rebirth that’s latent throughout the film and it finishes on an interesting note with Longman and Hall apparent friends, suggesting an alliance with academia and the military that perhaps fuelled several other similarly themed films of the period (The Ipcress File certainly springs to mind).

It is strange how this film has become forgotten, especially as it follows Dearden and Bogarde’s celebrated collaboration Victim from 1961. All in all, and following my recent rediscovery of The Man Who Haunted Himself, I’d like to suggest a reappraisal of Dearden’s work. Or perhaps a select one, and I’ll be missing out Man in the Moon with Kenneth More.

In 1963 The Servant brought together the combined talents of Harold Pinter, Joseph Losey and Dirk Bogarde. Although he would subsequently write a mountain of screenplays, Pinter was at this time still new to cinema; his only other major piece for the big screen being the adaptation of his classic play The Caretaker. So whilst it’s difficult to imagine what the film’s original reception was like, it was likely to be one of surprise.

Pinter and Losey were to embark on a fruitful partnership over the next decade which would also produce Accident and The Go Between, but The Servant was new ground for both of them. Previously, Losey had directed a diverse range of films including The Boy With Green Hair, The Criminal and the bizarre Hammer masterpeice The Damned. Coincidentally, Losey’s oddest film to date The Sleeping Tiger also starred the well known actor called Dirk Bogarde, the matinee idol desperate to shake off his lightweight shackles. After slowly edging towards greatness, The Servant would finally be the film that earned Bogarde the respect he demanded.

Everything about Dirk Bogarde’s performance in The Servant is perfect. There’s the sense that he put everything into it; he’d finally found a film that would shape his career exactly to his fancy. Sure, two years earlier his role in Victim was admirably daring, but Victim stands as a film with a clear agenda. In contrast, The Servant is darker, ambiguous, menacing and very unclear in its stance on sexuality. And although Bogarde appears to be boldly saying here I am, I’ve finally arrived he is oh so careful to get it right; subtle in his portrayal of Barrett, effortlessly creating this brooding and seething man. Every look is right; every rolled eye, every insouciant stare, every flick of the hair. Even the way he smokes is spot on.

It’s easy to summarise The Servant as a film about a master/servant relationship that appears to reverse itself over time. Seeing it again, I now think the true meaning of the film is far more complex. Tony (James Fox) and Barrett (Bogarde) first appear as a rather odd embodiment of the rich young man and his manservant, Bogarde drawing out the mismatch in their relationship. Rather than requiring a manservant for reasons of class and wealth, Fox is physically needy, weak and vulnerable (throughout the film we see Bogarde tending to him, nursing either colds or hangovers). Bogarde draws on this rather well, making Barrett the stronger of the two. If Pinter and Losey are showing you that the traditional master/servant relationship doesn’t really work in the conventional sense, they present us with the master/servant relationship according to their version of the world. And LoseyPinterworld is far more interesting; Barrett I believe is still the servant when the film ends, but in a world where the edges are peeled back to reveal corruption and insanity.

The Servant isn’t purely a vehicle for Bogarde, even though he is the best thing in it. James Fox is very well cast as Tony; I can’t think of anyone else who could have suited the role so snugly. Similarly, Wendy Craig and Sarah Miles complete the quartet of genius casting. Craig is perfect as the plain Susan, the young woman with whom Tony begins a chaste liaison. In a rare straight role before comedy stole her, Craig maintains the careful equilibrium of the film. Similarly, Miles is sensational as Vera, Hugo Barrett’s “sister”, who turns up out of the blue to give Tony his sexual awakening. In Pinter’s hands, the seduction scene is painfully stark and a voyeuristic pleasure. At least it was for me.

Losey’s direction is also worth a mention. The black and white photography, mostly in the claustrophobic interior of Tony’s house, is excellent. He makes subtle use of mirrors and cast shadows that lesser directors would only stumble over. If I have any criticism of this film then it is possibly the weird interlude where Fox and Craig visit a restaurant and we are allowed to eavesdrop on the other diners (who include Patrick Magee and Pinter himself). It’s an entertaining scene, although ultimately pointless in the scheme of the film.

The Servant is a difficult experience. It’s at times painful viewing, but it’s also an incredibly rich and powerful piece. Sometimes it’s worth being taken just the little bit further. And unlike many of its contemporaries, it hasn’t dated at all. And although Bogarde – especially in his own eyes – went on to even greater achievements, I think this is his finest role. Worth comparing with the other Pinter/Losey/Bogarde collaboration Accident and with Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell’s Performance, which showed another side to London depravity and just how far you could push James Fox before he went over the edge.

|

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.