The first of two halloween posts this year.

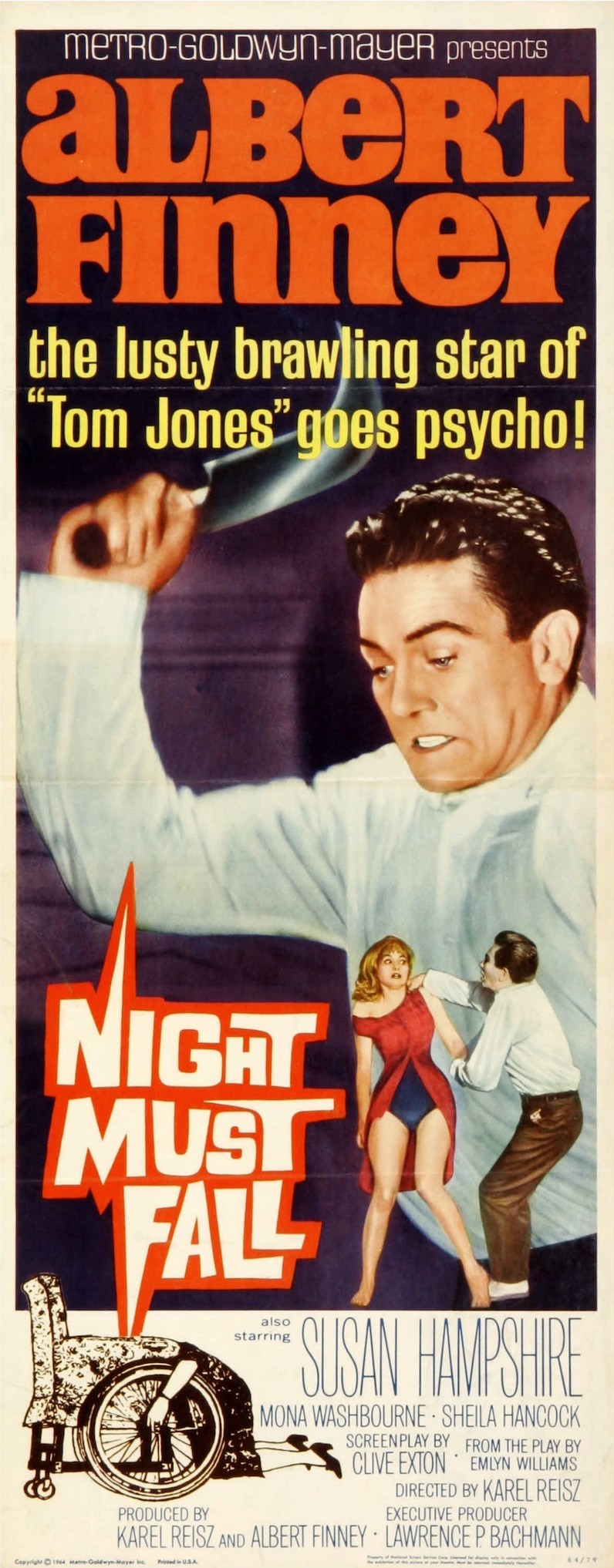

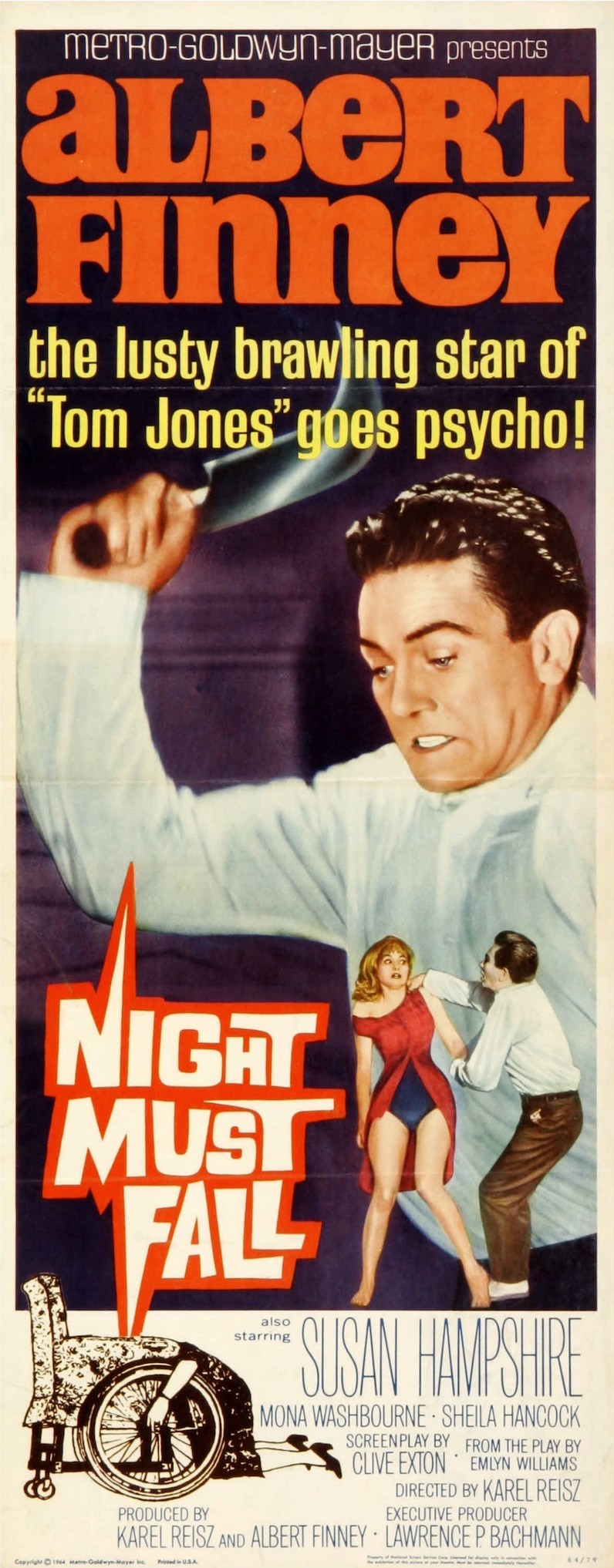

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

The tag line for many of Night Must Fall’s original posters reads “the lusty bawling star of Tom Jones goes psycho”, so while audiences weren’t allowed to forget Finney’s most recent success, they were also enticed into seeing the new movie idol in a more controversial role. Hitchcock’s Psycho obviously still very much in the public consciousness at the time, the film’s marketing must have suggested that Finney was exploring Norman Bates territory.

If Wikipedia is anything to go by, Finney was one of the top ten box office stars at the time, so this film was a bold move for the actor who turned down Lawrence of Arabia. But unfortunately Night Must Fall was not a success and is mostly forgotten, perhaps the least remembered film of an actor who starred in comparatively few films anyway (indeed, Night Must Fall was only his fourth film and he chose to give the cinema a rest for three years after this, returning in 1967 with the equally odd Charlie Bubbles).

Night Must Fall is a remake of an even lesser known 1937 film of the same name, which was in turn based on the 1935 play by Emlyn Williams. With Reisz directing from a script by Clive Exton (who also wrote the screenplay for 10 Rillington Place) and with Finney as producer, it also stars Mona Washbourne, Susan Hampshire and Sheila Hancock. The film was entered into the 14th Berlin International Film Festival. The excellent black and white cinematography is by Freddie Francis, and whilst some of the acting is decidedly (and deliberately) offbeat, if you can find a good print of the film it looks amazing.

Finney is the centrepiece as Danny, an odd young man who charms his way into the house of an apparent invalid Mrs Bramson (Washbourne) and her daughter Olivia (Hampshire) via his girlfriend, their housekeeper Dora (Hancock). Affecting a Welsh accent, Finney is determined to pull out all of the acting stops from the beginning and succeeds in delivering quite a mesmerising performance. He makes it no secret he’s unhinged, and there’s no secret either that the brutal murder that forms the backdrop of the story is his responsibility. Going back to the Psycho comparisons, little is shown in terms of violence or bloodbath and brutal murder wise most is left to the imagination. Worming his way into her affections, Mrs Bramson allows Danny to call her “mother”, which leads to her downfall. So also, like Bates, Danny does appear to have parental issues that have led to his outlook on life, although it’s much more subtle here. And there’s many a quietly handled and telling scene; watch out for the “puzzle hand”.

Thinking about Night Must Fall and the period it was made, I’m inclined to place it somewhere between The Servant (1963) and The Collector (1965). The Servant because there are some similarities visually, there is the depiction of weird childish game playing, and the exploration of a class theme (although Danny’s wish to rise a social class is less explicit than Dirk Bogarde’s Barrett). The Collector because it was another film with American backing that placed a young British star (Terence Stamp) in a very peculiar and shockingly non-starry role. The Collector is a better and more convincing film in my view (and it also features Mona Washbourne) but Night Must Fall is still essential viewing.

Karel Reisz went on to direct Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment in 1966 which (along with Saturday Night and Sunday Morning) is a far more celebrated 60s film. Looking through Finney’s subsequent roles, I can’t really see anything he did that stands out in a way that Danny does. I’m willing to be challenged on this, but mostly he seems to have succeeded in his wish not to be pinned down in any way after his early success, moving between musical (Scrooge in 1970), detective (as the original Poirot in 1974’s Murder on the Orient Express) and horror (Wolfen in 1980) genres. And most recently James Bond: he’s the best thing in 2012’s otherwise dire Skyfall.

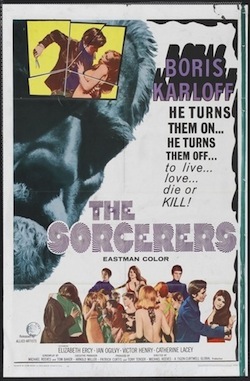

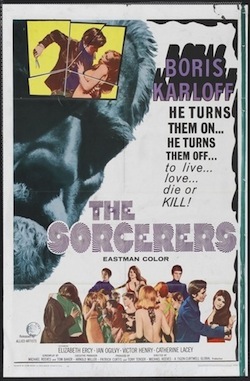

Although Boris Karloff enjoyed a very long career as an actor, it’s interesting that two of his best films came at the end of his life. At the age of almost eighty, he appeared in Michael Reeves’ The Sorcerers (1967) and Peter Bogdanovitch’s Targets (1968). A passable third late classic Karloff is also the quite mad but marvellous I tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath) from 1963.

Neither Targets or Black Sabbath are ever shown these days, but I’m choosing to celebrate the more widely available The Sorcerers. It’s a favourite of mine because it gives a fascinating view of “swinging” London at the time and is directed by Michael Reeves, also responsible for Witchfinder General and whose career ended suddenly with his death in 1969.

Neither Targets or Black Sabbath are ever shown these days, but I’m choosing to celebrate the more widely available The Sorcerers. It’s a favourite of mine because it gives a fascinating view of “swinging” London at the time and is directed by Michael Reeves, also responsible for Witchfinder General and whose career ended suddenly with his death in 1969.

The Sorcerers is fairly low budget, many of its scenes set in the interior of an unconvincing nightclub, where our leads look very bored and drink bottle after bottle of flat looking coke. The film also harks back to an era where detectives smoked pipes indoors and drove at dangerous speeds in Black Marias. Although 1967 spells Eastman colour so this is interesting as Karloff is usually recalled from his monochrome days.

Karloff plays Professor Marcus Monserrat, a hypnotist of sorts, who lives with his excitable wife Estelle (Catherine Lacey). They are searching for a young person to experiment on with their thought experiments which are controlled via some mind bending machinery and vivid light displays that would have no doubt excited the members of the early Pink Floyd. Indeed, the film is quick to expose the callowness of youth in the person of Mike Roscoe (Ian Ogilvy). Mike hangs out with Nicole (Elizabeth Ercy) and Alan (Victor Henry), it obvious fairly early that three is a bit of a crowd. Monserrat approaches Mike in a Wimpy bar, taking him home to try a little hypnotic experiment. From here things go swiftly and steadily wrong.

At first the sorcerers indulge in quaint little attempts at mind control; Mike breaks an egg and they experience the feeling by proxy of the cold yolk in their own hands. The experiments become increasingly more risky; stealing a fur coat, a high speed motorbike ride (without helmets) and a fight. Inevitably, the Monserrats and their puppetry lead to a murder or two (with one of the victims a young Susan George).

The best thing in The Sorcerers is Catherine Lacey, who is increasingly chilling as Estelle as she pushes the experiment further than envisaged and eventually overcomes the mostly benign Monserrat. Poor old chap, it wasn’t really what he’d bargained for.

A minor gem of a movie. Michael Reeves also directed La sorella di Satana (The She Beast) in 1965 which starred Barbara Steele and again the long suffering Ian Ogilvy. Reeves was also hooked up to work with Christopher Lee and Vincent Price on The Oblong Box (1969) but sadly it wasn’t to be.

Where Eagles Dare

Friday November 25, 2011

in 60s cinema |

Major, right now you got me about as confused as I ever hope to be.

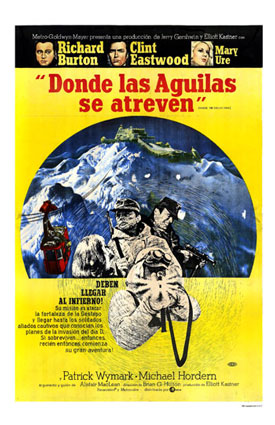

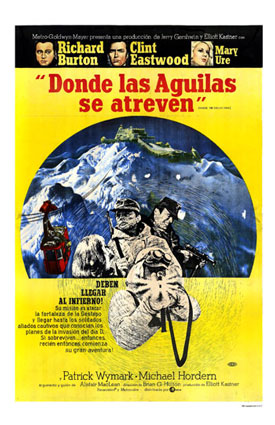

Mostly set with the backdrop of virgin snow, Where Eagles Dare is as close to a perfect Christmas movie as you’re going to get. It is also one of the most enjoyable films ever made; a perfect boy’s own romp that’s only spoilt if you happen to question the premise that Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood make plausible German soldiers. And that Burton, a legendary drinker at the time, can convincingly leap from the top of one cable car to the next. But it all adds to the fun.

The plot is a comic strip affair. A fast moving caper featuring the most modish looking white parkas you’ll ever see. Hollister has nothing on them. A U.S. General, one of the brains behind D-Day, is captured by the Germans. He is taken to the Schloß Adler, a castle built strategically high in the Alps and headquarters of the SS. A team is assembled and briefed by two very British MI6 officers, Colonel Turner (Patrick Wymark) and Admiral Rolland (Michael Hordern). They are led by Major John Smith (Burton) and the American Lieutenant Morris Schaffer (Eastwood). Their mission is to parachute down, slip in to the castle, and rescue the General before the Germans can question him. Easy. Another agent, Mary Elison (Mary Ure), joins the mission in secret, known only to Smith.

The plot is a comic strip affair. A fast moving caper featuring the most modish looking white parkas you’ll ever see. Hollister has nothing on them. A U.S. General, one of the brains behind D-Day, is captured by the Germans. He is taken to the Schloß Adler, a castle built strategically high in the Alps and headquarters of the SS. A team is assembled and briefed by two very British MI6 officers, Colonel Turner (Patrick Wymark) and Admiral Rolland (Michael Hordern). They are led by Major John Smith (Burton) and the American Lieutenant Morris Schaffer (Eastwood). Their mission is to parachute down, slip in to the castle, and rescue the General before the Germans can question him. Easy. Another agent, Mary Elison (Mary Ure), joins the mission in secret, known only to Smith.

As the mission kicks off, two members are mysteriously killed (including, sadly, the great Neil McCarthy), but Smith ploughs on, keeping Schaffer as a close ally and secretly updating Rolland on developments by radio using the call sign ‘Broadsword’. As Broadsword he calls Rolland, who takes the alias “Danny Boy”. The film pans out as a visual joy: the snow, the aforementioned parkas and – before we know it – our heroes are drinking in a bar with Ingrid Pitt. What more could you ask for?

Smith and Schaffer are captured by the Germans following a bar room episode and separated from the surviving members of the mission, Thomas (William Squire), Berkeley (Peter Barkworth) and Christiansen (Donald Houston). These are an odd triumvirate; middle aged (and destined for lesser film and tv roles in the future). Why MI6 would seriously pick them for such an important mission is anybody’s guess. But their part in the tale will be revealed later. Smith and Schaffer escape their captors easily and hitch a ride on a cable car — risky, but the only approach to the castle. Mary, posing as a new maid, has been brought into the castle by Heidi (Pitt) and Major Von Hapen (Derren Nesbitt), a dastardly Gestapo officer, takes a shine to her. This is Nesbitt’s finest role. Watch and you will weep and the great loss here of this fine British actor – he should have done much more with his career (actually Derren Nesbitt was involved in some bad publicity in the 1970s when he was accused of mistreating his wife. No doubt this didn’t help to keep the good parts rolling in).

Mary helps the cold and weary Schaffer and Smith climb in through a window to access the castle. General Rosemeyer (Ferdy Mayne) impressively arrives in a helicopter. This – along with Polanski’s the Fearless Vampire Killers – is Mayne’s second great castle role of the 60s. He’s suited to it. Senior Nazis, vampires. Mayne’s your man. Another key baddie Colonel Kramer (Anton Diffring – who else?) joins him in interrogating the captured General. Well, I say interrogating. More sitting nonchalantly and sipping fine wines. Thomas and the others turn up and reveal themselves to be German double agents. Smith and Schaffer also casually intrude, but Smith suddenly appears to betray Schaffer, announcing himself as “Major Johann Schmidt” of SS Military Intelligence and calling Schaffer a “punk”. Ouch. Clint obviously remembered this turn of insult for his run of successful “Dirty” movies that started just two years later…

Smith reveals the identity of the hostage general — just a humble actor posing — and also explains that Thomas and his gang are British impostors. To test them, he proposes they write the names of their fellow conspirators to be compared to the personal list in his pocket, and divulges the name of Germany’s top agent in Britain secretly to Kramer, who silently nods agreement. After the three finish their lists, Smith shows his own list to Kramer, which is a smart but blank notebook. To the general surprise, Smith admits the rescue operation was a cover for the real mission — to discover the identities of German spies in Britain. Touché!

Meanwhile, Mary, preparing some explosives (there are a lot of explosives in this film, pockets full of them), runs into von Hapen again; he takes her to the castle’s cafe (not bad, considering), and presses her to recite the tale of her assumed identity. He queries her story, prompting him to investigate – but walks in just Smith finishes his own absurd story. Mary’s entrance distracts him and the entire German baddie collective is shot, after which the group escapes with Thomas, Berkeley and Christiansen as prisoners. Schaffer sets explosives everywhere to create diversions, and Smith takes the group to the radio room, where he informs Rolland of their success. Or Danny Boy, who he contacts under the alias of Broadsword. It takes him a while, calling Danny Boy repeatedly under the alias of Broadsword. Eastwood goes to town with a machine gun in each hand. It’s really rather incredible.

They proceed to battle their way to the cable car station; Thomas is sacrificed as a decoy, and Berkeley and Christiansen attempt their own escape, but Smith climbs atop a cable car, destroys it with an explosive and then jumps on another to join the others, them all leaping mid-descent to board a smart red bus, prepared earlier as their escape vehicle. They drive like mad to an airfield with soldiers in pursuit, and barely make it onto a disguised getaway plane, where Colonel Turner is waiting for them.

Smith briefs Turner on the mission and confirms the suspicion that Turner is indeed the top Nazi agent in Britain, whose name the late Kramer had agreed to before; Turner had been lured into participating so MI6 could expose him, with Mary (Smith’s trusted partner) and Schaffer (a clueless American with no connection to MI6) specially assigned to the team to ensure the mission’s success. Turner attempts to shoot Smith, however MI6 made sure the firing-pin was removed as they knew he would attempt such a dastardly move. Deciding to save face, Turner commits suicide by jumping out of the plane. It’s a very chilling scene, with Patrick Wymark giving Burton a particularly old fashioned look before he steps out.

The film ends with Schaffer saying to Smith “Do me a favour, will ya. The next time you have one of these things, keep it an all British operation” to which Smith replies, “I’ll try, Lieutenant”. Clint Eastwood seems genuinely happy with this brief rapport, as is Burton. Where Eagles Dare was still early in Eastwood’s career. With only a few spaghetti westerns under his belt, he was still perhaps adjusting to his stardom – and I like to think his overall bafflement with the goings on in this film are genuine. On the other hand Richard Burton is obviously much more world weary. If rumour is true, and he was consuming several bottles of the hard stuff every day, it’s unlikely he had much recall of the film when it was completed. But he’s still fantastic, even if the stunt scenes have to be taken with a pinch of salt. But – as stories go – Burton and Eastwood both joked about the dominance of stunt extras. And although absurd, Where Eagles Dare has some excellent set pieces. Probably best is where Burton fights for cable car supremacy with Houston and Barkworth.

Cliché coming up, but one appropriate for such a fun film experience: ENJOY.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service

Sunday November 6, 2011

in 60s cinema |

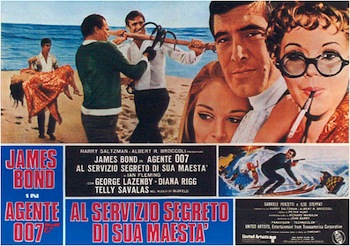

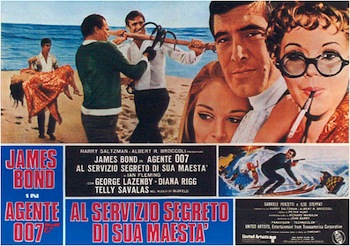

There’s a school of thought that places On Her Majesty’s Secret Service at the very top of the James Bond canon. The 1969 film is now slowly creeping into wider acceptance following the long vilification of George Lazenby’s performance. OHMSS has its flaws, but I’m beginning to agree that it’s the best of the series. There’s some excellent action scenes, mostly involving snow – there’s ski chases, an avalanche and a fight on a bobsleigh. There’s a good Ernst Stavro Blofeld in the shape of Telly Savalas and three Avengers girls. Well that’s an exaggeration. Honor Blackman appears only fleetingly in flashback and in her brief appearances Joanna Lumley looks so bored she’s in danger of falling asleep. But we get to see a lot of Diana Rigg.

In the late 60s Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman decided to produce a more realistic James Bond that would be closer to Ian Fleming’s novels than previous entries in the series. Less gadgets, fewer jokes, more of the tough and quick thinking spy. I think they largely pull of the attempt to provide a deeper and more character driven film. Interestingly, the impending 2012 Bond entry Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes, plans to do something similar and will also aim at a more character based piece. And looking back at the increasingly camp and jokey Bond films that followed the release of OHMSS – beginning with the dire and lazy Diamonds are Forever – Lazenby’s sole Bond effort has matured like a fine wine. Or martini, if you want to be cheesy.

In the late 60s Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman decided to produce a more realistic James Bond that would be closer to Ian Fleming’s novels than previous entries in the series. Less gadgets, fewer jokes, more of the tough and quick thinking spy. I think they largely pull of the attempt to provide a deeper and more character driven film. Interestingly, the impending 2012 Bond entry Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes, plans to do something similar and will also aim at a more character based piece. And looking back at the increasingly camp and jokey Bond films that followed the release of OHMSS – beginning with the dire and lazy Diamonds are Forever – Lazenby’s sole Bond effort has matured like a fine wine. Or martini, if you want to be cheesy.

Plot-wise, there’s nothing out of the ordinary about OHMSS. Starting in Portugal, our new Bond is introduced as he follows a mysterious woman (Diana Rigg) and eventually saves her from drowning herself. However, he’s attacked on the beach by baddies and she escapes. Lazenby’s first line is the joke “this never happened to the other fellar”. Following the opening titles (disappointing, which feature a montage of scenes from previous films) Bond meets Rigg again in a casino, or Contessa Teresa “Tracy” di Vicenzo as she’s known. Rigg is slightly offbeat as the Bond girl, and in an alternative universe this part would have been played by Brigitte Bardot (who decided to star in Shalako with Connery instead). Anyway,Bond is kidnapped while leaving the hotel, and they take him to meet Marc-Ange Draco (Gabriele Ferzetti), the head of a European crime syndicate. Draco reveals that he’s Tracy’s Dad and tells Bond of her troubled past, offering him one million pounds to marry her. Bond refuses, but agrees to continue courting Tracy under the agreement that Draco reveals the whereabouts of Blofeld, boss of SPECTRE.

After a brief argument with the tetchy M (the marvellous Bernard Lee) and the usual flirtation with Miss Moneypenny (Lois Maxwell) at MI6, Bond heads for Draco’s birthday party in Portugal. There, Bond and Tracy begin a romance, and Draco sends Bond off to a law firm in Switzerland. There, he breaks in to the office of a lawyer, and finds out Blofeld is corresponding with the London College of Arms’ genealogist Sir Hilary Bray, attempting to claim the catchy title “Comte Balthazar de Bleuchamp”. He does this with the assistance of a bizarre 60s safe-cracking “computer” which is so bulky it has to be lifted in by crane by a fellow agent under cover in a nearby building site. It does the job, although these days I imagine you’d be able to do the whole thing with an app.

Bray is played by George Baker and somebody along the line made the unwise choice of allowing Baker to dub Lazenby’s voice when Bond impersonates him. It leads to an uncomfortable half hour of the film which doesn’t help Lazenby’s case as an actor. Bond goes to meet Blofeld (Savalas – nicely oily in the role – he’s even cut his earlobes off to prepare himself for becoming Bleuchamp), who has established a clinical research institute in the Swiss Alps. There Bond meets a group of young women patients, the “Angels of Death” (including Lumley, Julie Ege and Catherine Schell). Bond later visits the room of one patient, Ruby (Angela Scoular – tragically to commit suicide in 2011), for a romantic encounter. Removing his kilt, Ruby responds by exclaiming “it’s true!” Later, Bond sees that Ruby, apparently along with each of the other girls, falls into a trance while Blofeld brainwashes them to distribute bacteriological warfare agents throughout various parts of the world. Blimey!

Bond as Bray tries to persuade Blofeld to leave Switzerland, so the British Secret Service can arrest him without violating Swiss sovereignty; Blofeld doesn’t want to and then rumbles him anyway, locking him in the control room of a cable car. After much clambering about, Bond escapes on skis – at one point losing a ski which results in the best one-legged ski chase in cinema. Bond later finds Tracy after being pursued through a busy Christmas fayre, very well executed and a rare scene where we see Bond scared. A blizzard forces them to a remote barn, where Bond proposes marriage. The next morning, Blofeld catches up with them after another ski chase. Here, Lazenby slips into Connery humour – when a baddie accidentally falls into a snow plough and is chopped to pieces he quips “he had guts”. The wicked Blofeld then causes an avalanche to stop our heroes, and captures Tracy.

Blofeld goes on to hold the world to ransom with the threat of destroying its agriculture using his brainwashed women (for added effect just imagine Joanna Lumley conquering the world), demanding amnesty for all past crimes and that he be recognised as the current Count de Bleauchamp. Fair enough? Not really, especially as we witness one of those excruciating scenes where the villain attempts to woo the heroine. With a glass of cheap wine and a fag. So Bond gets together with Draco to attack Blofeld’s headquarters and rescue Tracy. The headquarters characteristically explode, but Blofeld escapes in a bobsled, resulting in a high speed ice chase.

With only a few minutes left the film gears up for its extremely effective and downbeat ending which very neatly follows the intense chase scenes. Bond and Tracy get married in Portugal. They’re all there in their finery; M, Q and a tearful Moneypenny. The newlyweds drive away in Bond’s Aston Martin. When Bond pulls over to the roadside to remove flowers from the car, Blofeld and his partner in crime Irma Bunt (Ilse Steppat) commit a drive-by shooting that kills Tracy. A police officer pulls over to inspect the bullet-riddled car, prompting a tear-filled Bond to mutter that there is no need to hurry to call for help by saying, “We have all the time in the world”, as he cradles Tracy’s body. Close.

Director Peter R. Hunt does a fine job throughout – the obvious back projections typical of the era only spoiling the chase scenes slightly. This was his only Bond film as director (although he was involved with Dr No, Goldfinger and From Russia With Love as an editor). He did however direct two Roger Moore non-Bonds in the 70s, Gold and Shout at the Devil as well as working on The Persuaders! Perhaps more interestingly, Hunt worked as an editor on the Bond antidote The Ipcress File and there are some slight similarities, although this may be mostly down to the John Barry score. And I think George Lazenby, apart from the awkward Sir Hilary scenes, is fine too. Mainly perhaps because his presence is refreshing, and it’s easy to forget just how irritating Connery could be at times – something qualified when he crept back in Diamonds are Forever. Lazenby is in many ways the least conceited of the Bonds, and he convincingly suits the tough guy aspect of the role that’s also characteristic of Daniel Craig.

Possibly the most memorable feature of OHMSS is Diana Rigg, who appears as an ambiguous Bond girl in a gratingly masculine world. There’s the whole uncomfortable thing about her Dad paying Bond to marry her, and there is a scene where Draco punches her and knocks her out when she wants to go back to help Bond instead being bundled into a helicopter following her rescue. We don’t really find much about Tracy’s “troubled past” and perhaps the film could have dared to be more of the character study that it originally set out for. But Rigg has an undeniable screen glow, and it’s odd that the cinema didn’t do more with her.

George Lazenby quit the role during the shooting of OHMSS. Apparently his agent advised him that spy films were old hat. And it’s difficult to look through his subsequent CV without gritting one’s teeth. He’s kept himself busy, although the only thing I’m familiar with is the 1983 tv movie The Return of the Man from UNCLE where he plays a character called “JB”. However I would love to see the 1971 film Universal Soldier in which he co-starred with Germaine Greer. Now she would have had something to say to Draco.

John Barry’s music is as excellent as always, although essentially it is the same theme throughout the film and oddly there is no main title song as such and we miss Shirley Bassey or whoever belting it out. Still, there’s the more low key We Have All the Time in the World by Louis Armstrong which is more in keeping with the mood of the film and became much more well known a quarter of a century later. I watched the 2006 remastered OHMSS on DVD and it is a delight. It reminded me of the snow set cable car fest Where Eagles Dare from around the same time, which would serve as an excellent companion in a dream double bill. Broadsword calling Danny Boy…?

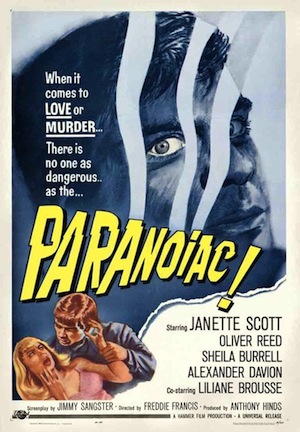

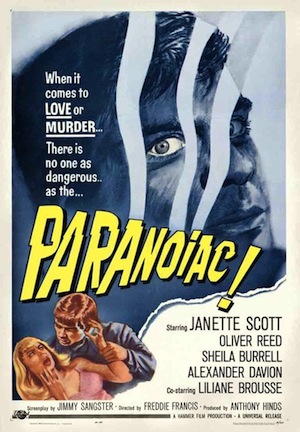

Hammer completists: look no further. Oliver Reed enthusiasts: welcome. Fans of obscure 60s British films: salut!

I’ve recently tracked down a copy of Paranoiac, a 1963 film directed by Freddie Francis, scripted by Jimmy Sangster and starring a young Oliver Reed. The film is part of Hammer’s series of psychological thrillers, that followed the success of Scream of Fear in 1961. Different from the usual Hammer output at the time, the films were in black and white and concentrated on non-supernatural plots in modern settings. They were also usually quite melodramatic. The general theme of Paranoiac is madness. Of the stark raving variety.

I’ve recently tracked down a copy of Paranoiac, a 1963 film directed by Freddie Francis, scripted by Jimmy Sangster and starring a young Oliver Reed. The film is part of Hammer’s series of psychological thrillers, that followed the success of Scream of Fear in 1961. Different from the usual Hammer output at the time, the films were in black and white and concentrated on non-supernatural plots in modern settings. They were also usually quite melodramatic. The general theme of Paranoiac is madness. Of the stark raving variety.

Oliver Reed plays Simon Ashby, a belligerent young man who is fond of a drink or two. He’s part of an odd family still reeling from the death of his parents in a plane crash and the apparent suicide of his elder brother Tony that followed the tragedy (apparent because – you’ve guessed it – the body was never found). Aunt Harriet (Sheila Burrell) and sister Eleanor (Janette Scott) share the Ashby country pile with difficult Simon. I say difficult because he’s portrayed by Reed at his drunken best. Although only receiving second billing to Scott he is the key actor in Paranoiac – reeling through the film in an inebriated rage, veering between leaning on family lawyer John Kossett (Maurice Denham) for cash handouts and racing home in his sports car to empty the brandy decanters and scream abuse at the servants. He’s a nasty young fellow and Reed plays him magnificently.

Things get off to an immediately creepy start in Paranoiac with Eleanor seeing glimpses of Tony hanging around, and this rather fragile young girl is pushed rather quickly to leaping off a cliff. Fortunately, Tony (Alexander Davion) seems benign as he saves her and is shockingly reintroduced into the family circle. Simon almost runs him over and then roars off in his car after ruining a flowerbed, whilst a suspicious Harriet turns him over to a grilling from Kossett. It’s all rather convenient you see, as Tony’s reappearance will grant him the Ashby fortune, otherwise due to Simon in a few weeks. Although something of a bugger for him, Simon doesn’t seem too bothered, his main concern being generally drunken and beastly. However Kossett subjects “Tony” to a “series of questions” (along the lines of “what did I buy you for your ninth birthday?”) to ensure that he really is the heir to the Ashby fortune.

Of course he isn’t, although they’re mostly fooled. “Tony”, it turns out, is in the services of Kossett’s crooked son (John Bonney), and matters aren’t helped by the still fragile Eleanor falling for him (together they escape the old trick of somebody tampering with the brakes on the car whilst they’re on a cliff edge picnic, Eleanor being saved from plunging to her doom yet again. Why do so many characters in so many films choose to have a picnic on a cliff edge?) Matters race towards an increasingly insane conclusion, with Reed pulling out all of the magnificent stops including wild eyed organ playing, masked knife-wielders, skeletons bricked up in basements and a concluding house fire.

Apart from Reed and Denham, the acting in the film is unmemorable. Lillian Brousse walks in and out as a French maid but is only irritating (as is Scott to be honest). Reed made several films for Hammer in the early 60s starting with small roles in the Two Faces of Dr Jekyll and Sword of Sherwood Forest in 1960. His first substantial part for them was in the more memorable The Curse of the Werewolf in 1961. Strangely, he was then moved from the horror genre to appear in more offbeat offerings over the next two years including Captain Clegg, The Scarlet Blade and The Damned. Most of these are now forgotten, although Joseph Losey’s The Damned turns up on television fairly regularly and is worth catching. In my view the 60s were Reed’s best decade as an actor by far.

Paranoiac is very low budget and very daft, although Oliver Reed does what he could do best – deliver an over the top although very entertaining performance. In his mid twenties, he looks trim and rather dashing. Some may even say that he was handsome at the time. I’ll let you be the judge of that.

Previous Page |

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

In 1964 Albert Finney worked again with the director Karel Reisz on Night Must Fall, following their first collaboration four years previously on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. Crucially the films bear no comparison at all, Finney proving his versatility and determination not to be typecast into any particular role or acting style.

Neither Targets or Black Sabbath are ever shown these days, but I’m choosing to celebrate the more widely available The Sorcerers. It’s a favourite of mine because it gives a fascinating view of “swinging” London at the time and is directed by Michael Reeves, also responsible for Witchfinder General and whose career ended suddenly with his death in 1969.

Neither Targets or Black Sabbath are ever shown these days, but I’m choosing to celebrate the more widely available The Sorcerers. It’s a favourite of mine because it gives a fascinating view of “swinging” London at the time and is directed by Michael Reeves, also responsible for Witchfinder General and whose career ended suddenly with his death in 1969. The plot is a comic strip affair. A fast moving caper featuring the most modish looking white parkas you’ll ever see. Hollister has nothing on them. A U.S. General, one of the brains behind D-Day, is captured by the Germans. He is taken to the Schloß Adler, a castle built strategically high in the Alps and headquarters of the SS. A team is assembled and briefed by two very British MI6 officers, Colonel Turner (Patrick Wymark) and Admiral Rolland (Michael Hordern). They are led by Major John Smith (Burton) and the American Lieutenant Morris Schaffer (Eastwood). Their mission is to parachute down, slip in to the castle, and rescue the General before the Germans can question him. Easy. Another agent, Mary Elison (Mary Ure), joins the mission in secret, known only to Smith.

The plot is a comic strip affair. A fast moving caper featuring the most modish looking white parkas you’ll ever see. Hollister has nothing on them. A U.S. General, one of the brains behind D-Day, is captured by the Germans. He is taken to the Schloß Adler, a castle built strategically high in the Alps and headquarters of the SS. A team is assembled and briefed by two very British MI6 officers, Colonel Turner (Patrick Wymark) and Admiral Rolland (Michael Hordern). They are led by Major John Smith (Burton) and the American Lieutenant Morris Schaffer (Eastwood). Their mission is to parachute down, slip in to the castle, and rescue the General before the Germans can question him. Easy. Another agent, Mary Elison (Mary Ure), joins the mission in secret, known only to Smith. In the late 60s Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman decided to produce a more realistic James Bond that would be closer to Ian Fleming’s novels than previous entries in the series. Less gadgets, fewer jokes, more of the tough and quick thinking spy. I think they largely pull of the attempt to provide a deeper and more character driven film. Interestingly, the impending 2012 Bond entry Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes, plans to do something similar and will also aim at a more character based piece. And looking back at the increasingly camp and jokey Bond films that followed the release of

In the late 60s Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman decided to produce a more realistic James Bond that would be closer to Ian Fleming’s novels than previous entries in the series. Less gadgets, fewer jokes, more of the tough and quick thinking spy. I think they largely pull of the attempt to provide a deeper and more character driven film. Interestingly, the impending 2012 Bond entry Skyfall, directed by Sam Mendes, plans to do something similar and will also aim at a more character based piece. And looking back at the increasingly camp and jokey Bond films that followed the release of  I’ve recently tracked down a copy of Paranoiac, a 1963 film directed by Freddie Francis, scripted by Jimmy Sangster and starring a young Oliver Reed. The film is part of Hammer’s series of psychological thrillers, that followed the success of

I’ve recently tracked down a copy of Paranoiac, a 1963 film directed by Freddie Francis, scripted by Jimmy Sangster and starring a young Oliver Reed. The film is part of Hammer’s series of psychological thrillers, that followed the success of