1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

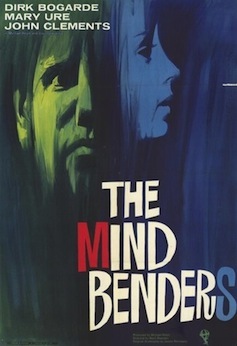

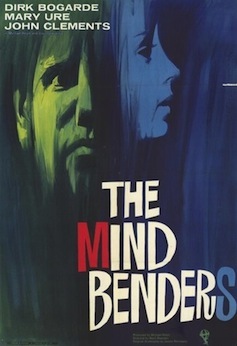

The last of the bunch was The Mind Benders, a film directed by Basil Dearden that has now unjustly dropped into obscurity. Bogarde stars as Dr Henry Longman, a scientist dabbling in experiments in isolation. Although sometimes billed as science fiction or as an early cold war thriller, and the subject matter hints at 60s hallucinogenic cinema, The Mind Benders doesn’t neatly fit into any genre. However it is an absorbing and literate film that’s worth seeking out.

The film opens with Professor Sharpey (Harold Goldblatt) throwing himself from a moving train on route to Oxford University. A large sum of money is found on him and upright Major Hall (John Clements) assumes that the unfortunate don was a traitor, selling secrets to the Russians. Hall goes on to discover that Sharpey was working on isolation experiments with his colleagues Dr Tate (Michael Bryant) and Longman, with Sharpey and Longman actively taking part in the tests. A man born to snoop around, Hall confronts Longman with the suggestion of Sharpey’s treason and an unconvinced Longman talks himself into allowing Hall to witness an isolation experiment. With Longman as the subject…

This is a film devoid of special effects or sensation. However the black and white photography of The Mind Benders helps to enhance the creepy presence of the isolation chamber, a huge water tank where Longman is suspended without light, sound or feeling. Tate and Hall observe him as he passes through several states of consciousness, including confusion, panic and hallucination, in a marathon seven hour session. The chamber is likened to something from Frankenstein and this is how we perceive Longman as he emerges from it – almost a rebirth as he comprehends reality with wide, frightened eyes. And this is one of the great Bogarde performances; at this point we know that he’s really going to get his teeth into the part.

Hall believes that Sharpey was brainwashed, and that a man fresh from the isolation tank is open to interrogation and suggestion. Here lies the crux of the film. He coerces Tate into a further experiment, where they taunt the vulnerable Longman with improper suggestions about his wife Oonagh (Mary Ure). Hall believes, rather naively, that whatever wrong they do to Longman can be undone (a bent mind can be unbent so to speak). And whilst Longman appears to quickly recover from his ordeal and it seems that the brainwashing aspect of the experiment has failed, we know that something is going to be amiss, and the second act begins with Tate visiting the now visibly odd Longman (Bogarde manages to make use of a pair of glasses alone to appear effectively sinister) and the now pregnant Oonagh. The rest of the film plays out with Tate and Longman wresting with their own uncontrollable Frankenstein’s monster in the shape of Bogarde at his nastiest.

The Mind Benders is a very talky film but saved by excellent performances all round. Ure is as good as Bogarde as the unfortunate Oonagh, and Wendy Craig (who also appeared in The Servant) has a supporting role. The ending, which I won’t give away, drives home the theme of rebirth that’s latent throughout the film and it finishes on an interesting note with Longman and Hall apparent friends, suggesting an alliance with academia and the military that perhaps fuelled several other similarly themed films of the period (The Ipcress File certainly springs to mind).

It is strange how this film has become forgotten, especially as it follows Dearden and Bogarde’s celebrated collaboration Victim from 1961. All in all, and following my recent rediscovery of The Man Who Haunted Himself, I’d like to suggest a reappraisal of Dearden’s work. Or perhaps a select one, and I’ll be missing out Man in the Moon with Kenneth More.

In The Life and Death of Peter Sellers Roger Lewis tracks down every one of the more obscure films that Sellers made. For such a renowned actor, it’s incredible that many of his movies were left unreleased. For example, there is only one print in existence of Mr Topaze, his sole directorial effort, a film he attempted to destroy the negative of. Lewis does remarkably well with his detective work, making it an obsession to see the entire Sellers output. The only film that escapes him is A Day at the Beach, his desire to see this forgotten gem being dedicated to an entire chapter. Fifteen years after the publication of the Sellers biography, A Day at the Beach is now widely available.

A Day at the Beach is legendary for three reasons.

A Day at the Beach is legendary for three reasons.

That it features Sellers in an uncredited cameo, that it was forgotten for so long, and for Roman Polanski.

Next to the obscure sex comedy What? this is the least known of Polanski’s films. He wrote the screenplay in 1968 but, devastated by the murder of Sharon Tate the following year, passed over directorial duties to Simon Hesera. There’s some debate over how much of the film, if any, that Polanski directed. There’s certainly his trademark style in evidence, and apparently he had a hand in the editing. Nevertheless it sits comfortably with his films of the period, most notably Cul de Sac, and the seaside settings do tend to link his otherwise unrelated works down the years. For example, the stunning location work of The Ghost.

A Day at the Beach is a bleak study of a hopeless alcoholic. Mark Burns plays a desperate drinker and would be intellectual called Bernie who embarks on a day out with a young girl, who we presume is his daughter. The film follows the tragic path of a day spent in the pursuit of drink and ends depressingly.

At this point you may be forgiven for asking what exactly all this has to do with Peter Sellers. Well he enters proceedings during the course of the day, along with Graham Stark, and they feature as a pair of outrageously camp homosexuals. Bernie is rude to them, although succeeds in extracting a few bottles of their beer. It’s a peculiar scene, Sellers and Stark are hilarious in their fleeting appearance, but I think the performances are better than caricature. Until very recently the Sellers episode was available on YouTube, although it’s now been removed. Obviously far too public for a film that wishes to remain in the dark.

Completed in 1970, A Day at the Beach was released in 1972 before vanishing for several decades. Mark Burns, who died in 2007, never saw the film. Polanski, to my knowledge, has never publicly commented on or even acknowledged it. Apparently Sellers and Polanski were good friends. An odd mix, especially as The Life and Death of Peter Sellers uncovers very few people willing to admit to any affection for Sellers, and the book largely aims to portray him as a megalomaniac, a selfish, uncompromising lunatic. But a genius nevertheless, and this is perhaps where he connected with Polanski. A Day at the Beach is a bizarre product of this friendship. And it would be interesting to catch up with Roger Lewis about it.

A Day at the Beach is also worth catching for a wonderful cameo from the Polanski regular Jack MacGowran, playing a particularly defensive deck chair attendant. For a film that’s taken so long to see the light of day, it’s certainly worth a look.

A cinematic treat for Hallowe’en. Dance of the Vampires.

A cinematic treat for Hallowe’en. Dance of the Vampires.

Dance of the Vampires is a film that often graces the Christmas tv schedules, its elements of fairy tale, horror and offbeat comedy making particularly welcome viewing at that time of year. But it’s also a film that’s recently slipped into obscurity, being unfairly called a horror spoof where it is a far superior piece of cinema compared to the Hammer output of the time, outranking them in sheer quality of acting, costume and set design, script and music.

Perhaps it isn’t so odd that the film has failed to find a secure footing in the horror canon. When it was first released in 1967 director, co-screenwriter and star Roman Polanski disowned the film. The original title was changed to The Fearless Vampire Killers, or Pardon Me, Your Teeth are in my Neck for the US release and this version was rather brutally cut. To make matters worse the original trailers for the film market it along similar lines to Carry on Screaming from the same era. Movie posters from around the world also sell the film as anything from soft porn vampirism (pictured, and Sharon Tate went a little way to embellish this with her on set Playboy shots) to something quite cartoonish (unfortunately the most recent DVD release plumps for the latter). So sadly Dance of the Vampires has hung around as a somewhat doomed affair, misfiled in the annals of film and unjustly ignored.

Dance of the Vampires was filmed in 1966 at the height of Hammer’s success. The same year saw the release of Frankenstein Created Woman and Dracula Prince of Darkness, arguably two of the studio’s finest films. Although however much I admire these films I still think that Dance of the Vampires towers above them. Firstly it’s the breathtaking quality of the film. Polanski is a gifted director and it is well paced, thoughtful and technically faultless. The set design is outstanding, in particular the interior of the vampire castle where the slightly claustrophobic feeling invites a comparison with how the director captured the inside of the Dakota in New York for Rosemary’s Baby which followed a year later.

The wonderful soundtrack is by Krzysztof Komeda, who composed the music for Rosemary’s Baby and Polanski’s earlier film Cul-de-Sac. Sadly Komeda was to die in 1969 and Roman’s subsequent films all miss his added value. Dance of the Vampires has one of the all time great movie soundtracks, entirely fitting for the subject matter. The opening theme places the viewer directly into the fairy tale landscape of the film and continues to haunt throughout.

And it’s the haunting nature of the fairy tale that works so well in its favour, superbly written by Polanski and his usual collaborator at the time Gerald Brach. The film opens with Jack MacGowran and Polanski as two inefficient vampire hunters. MacGowran is superb as the elderly Professor Abronsius, bringing a new level to eccentricity to the sphere of vampirism. He’s a rather endearing character, his eyes lighting up when he asks the locals “is there a castle in the district?” He’s even more delighted by the news that, when visiting the said castle, he discovers an extensive library – and dances with delight. Polanski is Alfred, his assistant. He’s a rather shy young man who attempts to woo the object of his affection Sarah (Sharon Tate) by building snowmen. When given the opportunity to kill the sleeping Count von Krolock (Ferdy Mayne) in his crypt he chickens out, hinting that events may lead to a particularly downbeat conclusion.

Snow features prominently in the film. The Professor and Alfred embark on a Beatlesque ski ride and later clamber over the snow covered castle battlements. In a memorable scene, Sarah is perplexed when the bubbles in her bath turn to snow. She looks up to find von Krolock descending from above to abduct her. There are many such touches resulting from Polanski’s imagination and the luxury of a large budget (indeed, this was his first colour film and he chose to make it in anamorphic format, filming on location in The Alps). The set design is finely detailed, right down to the coachwork on the castle doors and the decaying cobwebs. The vampire dance itself, which comes at the end of the film, is a brilliant work of choreography. Even Leslie Halliwell, normally dismissive of this kind of picture from this era, had to admit it was impressive.

Polanski makes a rare appearance in one of his own films. His other substantial role being the Tenant (1976) . He is a great and little used actor, although Jack MacGowran undoubtedly gives the best performance in Dance of the Vampires. MacGowran was something of a Polanski regular in the late 60s. He’d appeared as the ill-fated Albie in Cul-de-Sac and was later to feature in arguably the most obscure entry into the Polanski canon, A Day at the Beach (1970), a film produced and scripted by Polanski which subsequently vanished for several decades. He also starred in the Gerald Brach scripted and George Harrison scored Wonderwall (1968), his only proper starring role. MacGowran, an interpreter of Samuel Beckett – there’s a splendid tv version of Eh, Joe? – is now sadly forgotten.

Alfie Bass adds some knockabout comedy as Sarah’s father, Shagal the innkeeper. Becoming a vampire himself, he laughs off attempts to repel him with a crucifix – “you’ve got the wrong vampire” – as he is of the Jewish persuasion. Although he doesn’t have a great deal to do Ferdy Mayne is an impressive count, whilst Iain Quarrier plays his homosexual son. Perhaps this is one of the first gay vampires in cinema. The boxer Terry Downes appears as the silent and grotesque hunchback Koukol and it’s to his credit that he doesn’t make this character too absurd. And we mustn’t forget Sharon Tate. It’s well documented that Polanski fell in love with her during the making of this film (there’s a tiny clue in the opening credits). Although Tate’s appearances are really only fleeting, she radiates a rare and captivating beauty. It would have been a lesser piece of work without her.

Seeing the film again I was impressed by how stunning it looks in widescreen. It’s infinitely superior to the various tv versions and I can understand the director’s fury over its initial treatment. Apart from the look and charm of the film the other satisfying element of Dance of the Vampires is that the bad guys win. By travelling into the heart of Transylvania to stamp out vampirism, the inept Alfred and the Professor instead fail and succeed in ferrying it back with them to the modern world. In the comfortable world of Hammer that would never happen.

Billy Liar

Friday September 24, 2010

in 60s cinema |

Today’s a day of big decisions – going to start writing me novel – 2000 words every day, going to start getting up in the morning. [Looks at his overgrown thumbnail] I’ll cut that for a start. Yes… today’s a day of big decisions.

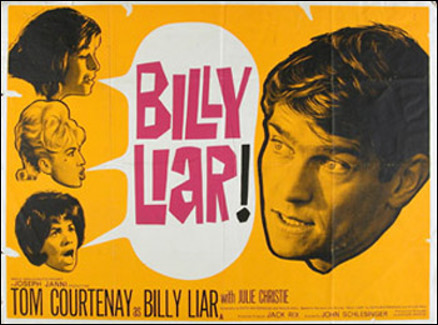

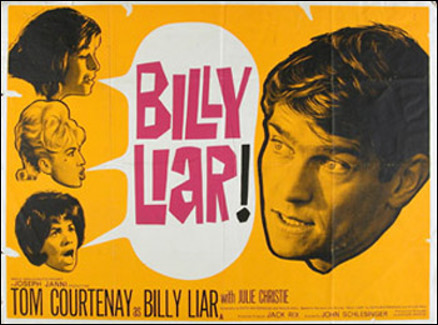

Billy Liar came back into my orbit when the BBC screened their recent Up North season. Their excellent documentary on early 60s British cinema featured the usual, welcome, suspects of A Taste of Honey, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar. The last two were directed by John Schlesinger in 1962 and 1963 respectively. A Kind of Loving is one of my favourite films, a typical kitchen sink drama of the period but elevated by the captivating lead performance of Alan Bates. Billy Liar, starring Tom Courtenay, is equally terrific but for different reasons.

Billy Liar is a film dealing with flights of fancy; the life of a young man who lets his imagination get the better of him. Cheat, fool, wastrel, or simply liar. Permanently late for work, tying everyone in knots with his perpetual fibbing (“you told that woman down the fish shop that I had me leg off”, moans his father, “do I look like I’ve had me leg off?”) and general larking about. Tom Courtenay handles a difficult role admirably. I say difficult because a lesser actor would make him irritating, and Courtenay restrains himself enough to make Billy sympathetic. The role was originally played on stage by Albert Finney and it’s difficult to imagine him in the part; Finney’s a little too thick set and tough looking, whereas Courtenay does have that juvenile look about him. That’s not to say the Finney is a lesser actor, he’s just not Billy Fisher.

There’s plenty of fine performances in this film, especially the female characters. Billy’s mother (Mona Wasbourne) and grandmother (Ethel Griffies) represent the older generation with Barbara (Helen Fraser) and Rita (Gwendolyn Watts) are permanently wet and permanently shrieking in turn as the younger. Then there’s Julie Christie, perfect in the role of Liz, who only succeeds in sparking any kind of life in him. Billy’s dreams of achieving his ambition of becoming a comedy script writer in London for the excruciating Danny Boon (Leslie Randall) are realised via Liz. Almost.

Watching Billy Liar again for the first time in two decades or so, I was struck by how the effectiveness of the film’s ending hasn’t blunted at all. This is the inevitable closing scenes, where Billy deliberately misses the train that’s about to take him and Liz away to excitement, riches and a conventional happy ending. But Billy Liar resorts to its monochrome realism; tugged by the reality of his grandmother’s death and a family crisis he falls back into the persona of the dreamer and slopes home to his bedroom.

John Schlesinger’s direction is also worthy of a mention. Watching this on wide screen (the Studio Canal DVD I own is very good quality although annoyingly there are no extra features) I was struck by how beautifully photographed it is. Schlesinger also makes wonderful use of open space, especially the scene with Billy and Barbara in the enormous graveyard, the huge Victorian crypts speaking for themselves in metaphor. Most effectively was how he films the background to 60s life, a mix of demolition sites and newly minted tower blocks. And how he lovingly films Christie, a find for him after she’d only previously appeared in a couple of minor films (things like Crooks Anonymous with Leslie Phillips and Stanley Baxter in 1962).

Although he never again reached the heights of A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar, John Schlesinger did direct several more notable films. He worked with Julie Christie again in both Darling (1965) and Far From the Madding Crowd (1967). From there he delivered a run of eclectic films until his death in 2003, the best in my opinion being Midnight Cowboy (1969) and the unjustly forgotten The Day of the Locust (1975).

Billy Liar is a classic period piece and the best film of British 60s cinema. Although so rich in acting talent (I’ve neglected to mention Rodney Bewes and George Innes as Billy’s work pals) two performances deserve an extra special highlight. Firstly Wilfred Pickles is brilliant as Billy’s permanently aggravated father, and his exasperation provides the film with its best comedy. But best of all is Leonard Rossiter as Billy’s boss Mr Shadrack, where – if you look closely – you may see the seed of the performances he gave a decade and a half later as Rigsby in Rising Damp. Sheer genius.

Last night I watched The Rebel, part of the DVD Tony Hancock Collection and paired with The Punch and Judy Man. A slim volume, although Hancock only ever appeared in five feature films, and of the remaining three he was only cast in supporting roles. In his excellent biography of the comedy actor John Fisher examines radio and television, the worlds that Hancock conquered and made his own. Fisher even considers his achievements as a stage comedian in a new light. But sadly Hancock’s impression on the cinema is all too brief. It’s thankful then that The Rebel is one of the best British comedy film of the 1960s.

The Rebel essentially took the Hancock persona from television, casting him as a bored office worker who dreams of becoming a successful artist. The sad reality is that he is awful at art, producing childlike compositions of derision, known in the film as the infantile school. Travelling to Paris to find his fortune he is forced into the position of passing off the work of another artist as his own. He becomes hugely successful, but facing the pressure of having to produce more original work tracks down the other artist, only to discover that he has changed his style completely in a bid to to embrace the infantile school. These paintings also become a success.

Released in 1961, The Rebel is a rare example of Hancock in colour, contrasting sharply with the middling technical quality of his television work. It also exists as a fascinating period piece. Bowler-hatted commuters, offices with early adding machines, beatnik cafes all fall comfortably into place. It isn’t going too far to say that The Rebel epitomises the lost world of innocence that the era that produced it suggests. Age has matured its charm like a vintage port. Despairing at a fellow commuter, oblivious to his dull fate, he exclaims “if this train is still running in 1980, he’ll still be on it!”

There’s also the supporting cast. Throughout his radio and television careers Hancock regularly worked with the same repertory company of actors. Many of the surviving tv episodes from the late 50s are a joy to watch simply because of the strength of the support. The Rebel features Hugh Lloyd as a fellow commuter, John Le Mesurier as the stiff office manager and Liz Fraser and Mario Fabrizi as workers in a cafe (“froth? I want a cup of coffee – I don’t want to wash me clothes in it!”) and they are all fabulous. Unfortunately there is no Sid James but we can’t have it all.

Irene Handl is a welcome addition as landlady Mrs Crevatte (the role was played on television by Patricia Hayes). Handl is fantastic, rushing around her house with her bra straps hanging down over her shoulders. It’s here that we first witness Hancock’s “art”. “What’s that horrible thing?” demands Mrs Crevatte. “A self portrait” Hancock answers proudly only to meet the reply “who of?” “Laurel and Hardy!” he snaps in despair. The early scenes of the film are priceless comedy.

Paul Massie plays an essentially straight role as Hancock’s artist friend and George Sanders – a big star at the time – appears as an art dealer. Apparently he received a larger fee than Hancock. Dennis Price turns up as an avant garde artist called Jim Smith. Also look out for Nanette Newman and Oliver Reed in early roles. Interestingly, and unusually for a comedy film, Hancock changes gear to play the straighter scenes with Massie and does so admirably – revealing a depth to his acting that was never fully exploited. In this sense, together with its international flavour, the Rebel anticipates many of the later caper films of the 60s, where comic and straight actors played together in expensive looking European locations, for example The Pink Panther.

The DVD features commentary by writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson together with Hancock enthusiast Paul Merton. In many ways the commentary makes the film funnier, with the trio often falling into fits of laughter, especially in the scenes between Hancock and Handl. It’s like watching with a gang of obsessive friends, and there are many fascinating anecdotes I’d never heard before, such as the time Hancock embarked on a two day bender whilst garbed in the paint splatterd pyjames he wore after filming the “Jackson Pollock” scene.

A highly enjoyable experience. Incidentally, Galton and Simpson also confess to writing far too much material for this film; even after they edited it down it is still a trifle overlong, but I’ll forgive them for that. Who wouldn’t?

Previous Page |

Next Page

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

1963 was a busy year for Dirk Bogarde and he appeared in four very diverse films. A final outing as a now middle aged Simon Sparrow in Doctor in Distress, I Could Go On Singing with Judy Garland (for which he contributed some of the script) and of course Losey’s masterpiece The Servant.

A Day at the Beach is legendary for three reasons.

A Day at the Beach is legendary for three reasons.  A cinematic treat for Hallowe’en. Dance of the Vampires.

A cinematic treat for Hallowe’en. Dance of the Vampires.