Frankenstein Must be Destroyed

Released in 1967, Hammer’s Frankenstein Created Woman is arguably the best of the films starring Peter Cushing as the deranged baron. Two years later there followed Frankenstein Must be Destroyed, the next in the series that was a dark and disjointed piece that may qualify as one of Hammer’s strangest horrors.

Frankenstein Must be Destroyed has possibly the strongest cast ever assembled by Hammer. Cushing is supported by Simon Ward, Veronica Carlson and Maxine Audley. Freddie Jones makes the best of the post-Lee monsters, whilst Thorley Walters, Geoffrey Bayldon, George Pravda, Robert Gillespie and Windsor Davies are all excellent in supporting roles. As usual it is Cushing’s film, but here he portrays Baron Frankenstein with the nastiest of edges and resorts to the most unsavoury means to get what he wants. At times it’s uncomfortable viewing, with the image of the urbane Mr Cushing repeatedly crushed as he resorts to blackmail, rape and murder. Indeed, the scene in this film where he attacks a young woman in one of Hammer’s most disturbing, and unnecessary, scenes.

In following Frankenstein Created Woman, Frankenstein Must be Destroyed has a difficult task in standing up to the preceding classic. Where the previous film depicted the Baron pulling off the feat of tranferring a soul from one body to another, this shows him returning to more familiar pastimes of cutting and pasting body parts, in this case brains. This at least gives Hammer the chance to make this instalment the more blood curdling, and although we see much of squidgy brains being plopped into jars, there are still some marvellous moments that are purely suggestive – notably the scenes where Frankenstein asks his assistant to hold things tightly as he embarks on some noisy sawing through skulls.

Frankenstein Must be Destroyed begins by introducing the Baron at his most terrifying, Cushing apprehending an unwise burgler and garbed in a skull mask; a bizarre opening scene not properly explained but nevertheless effective. Frankenstein blackmails a young man (Simon Ward) into assisting him with his latest scheme, springing his former associate Dr Brandt (Pravda) from the local asylum and repairing his damaged brain by transplanting it into Professor Richter (Freddie Jones). Along the way mysterious events are followed by the local hapless police (Thorley Walters and Geoffrey Bayldon). The film doesn’t really kick in properly until the last act, where the new creature (Jones) escapes and attempts to return to his wife (Maxine Audley).

Both Freddie Jones and Maxine Audley are excellent, the former giving one of the most sympathetic portrayals of The Monster. Thorley Walters is also good, although it’s a shame Hammer chose not to pursue the Cushing/Wallters memorable double act from Frankenstein Created Woman. In 1969 Frankenstein Must be Destroyed ended the decade with something still recognisable from their greatest success a decade earlier. However the 70s would prove difficult times for them, with Frankenstein left to skulk in the shadows as they churned out more unmemorable Dracula vehicles, and eventually turned away from the classic monsters altogether.

I Start Counting

Thursday April 22, 2010

in 60s cinema |

With Walkabout and The Railway Children being enduring features of the television schedules, it’s odd that a far superior film starring the young Jenny Agutter is now totally forgotten. Made in 1969, I Start Counting was directed by David Greene and is a lost classic of British cinema. It’s one of the best depictions of that era I’ve seen on film; old buildings demolished for the New Town, quaint vehicles, short skirts and ugly shopping centres. It’s like a dose of late 60s Ken Loach but with the added spice of one of the more progressive Hammer films of the early 70s.

With Walkabout and The Railway Children being enduring features of the television schedules, it’s odd that a far superior film starring the young Jenny Agutter is now totally forgotten. Made in 1969, I Start Counting was directed by David Greene and is a lost classic of British cinema. It’s one of the best depictions of that era I’ve seen on film; old buildings demolished for the New Town, quaint vehicles, short skirts and ugly shopping centres. It’s like a dose of late 60s Ken Loach but with the added spice of one of the more progressive Hammer films of the early 70s.

I Start Counting is taken from a novel by Audrey Erskine-Lindop, which I suspect may be now even more obscure than the film. Agutter plays Wynne, an adopted 15 year old girl who is infatuated with her much older step brother David (Bryan Marshall). Sharing a cramped flat with the rest of the family, Wynne’s predicament is partly a claustrophobic study of sexual awakening. Added to this, she begins to suspect David as having some involvement in a local murder. She even covers for him, finding his blood stained clothes and burning them. What makes I Start Counting unusual, and especially for its period, is that the thriller aspect is kept very much as a back story; the film is confident to move at a slow although very involving pace, concentrating on Wynne’s journey into adulthood with her more precocious best friend Corinne (Clare Sutcliffe). Greene is also a skilled enough director to weave some subtle red herrings into the plot. You never really know where this film is leading you.

Undoubtedly some viewers will find this film dated, although for me this works in its favour by making it a superior period piece from 60s British movies. The observations made about the new replacing the old aren’t too overblown, and there is some scepticism surrounding the so called New Towns of the time; Wynne escapes her tower block life and finds solace by revisiting the now derelict former family home. Her trips into the countryside seem brief and eagerly snatched, but the natural environment appears dangerous to all else concerned. In one scene Wynne is feared missing, her trips to the old house seen as a foreshadowing of doom. There are other curious and subtle observations throughout; Corinne, fatally disadvantaged by her brash and outgoing nature, and the unusual ending which suggests that Wynne’s wishes may have come true.

I Start Counting has a very good, although mostly low profile, cast. Apart from Agutter, probably the most recognisable face is Simon Ward, who is impressive in the small yet pivotal role as a seedy bus conductor. Also look out for Michael Feast, contemporary of Bruce Robinson, playing a character with a very close resemblance to Danny in Withnail and I. Apart from this eccentricity, the performances are very naturalistic and convincing. Marshall and Sutcliffe are both excellent but Agutter is simply a revelation here. Nowhere else will you see her so wide eyed and impressionable. Cinema has committed a crime by not doing more with her.

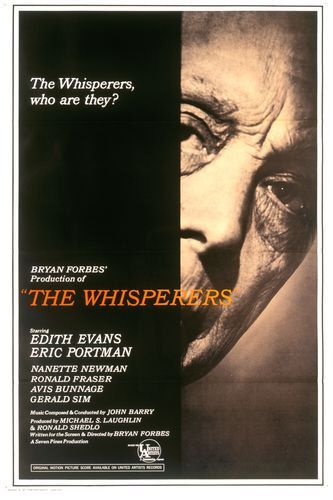

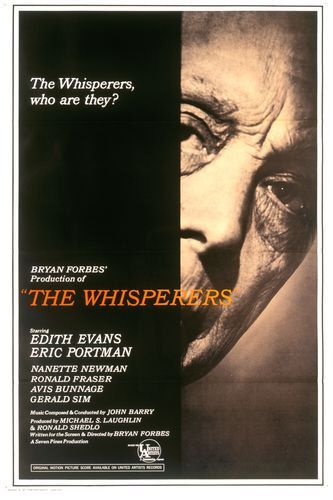

The Whisperers

Saturday March 13, 2010

in 60s cinema |

In 1967 Edith Evans was Oscar nominated for her role in the Bryan Forbes film The Whisperers. Although she lost out to Katherine Hepburn, Evans’ performance as Mrs Ross, the tired old lady lost in a world driven by the evils of money, is easily her best performance on film.

Although The Whisperers boasts an excellent John Barry soundtrack, it sits far away from the usual Barry fare of stylish spy thrillers typical of the decade. Barry’s long partnership with Forbes (which included the similarly moody Seance on a Wet Afternoon) allowed him to compose for a different view of the 60s, one shot in stark black and white where the poor struggled on a meagre existence. Forbes depicts this in the early scenes of The Whisperers; a cold and miserable winter, the library full of the old as they huddle against the warm pipes, the needy shuffling along a line at the social services.

Although The Whisperers boasts an excellent John Barry soundtrack, it sits far away from the usual Barry fare of stylish spy thrillers typical of the decade. Barry’s long partnership with Forbes (which included the similarly moody Seance on a Wet Afternoon) allowed him to compose for a different view of the 60s, one shot in stark black and white where the poor struggled on a meagre existence. Forbes depicts this in the early scenes of The Whisperers; a cold and miserable winter, the library full of the old as they huddle against the warm pipes, the needy shuffling along a line at the social services.

Evans (who was nearing eighty at the time) is superb as Mrs Ross, slipping into dementia and believing both that she is watched by unseen guests in her room, the whisperers concealed within a dripping tap or behind the wall, and that she will soon receive the estate of her long dead father. Reality swirls around her, the young couple living above (who include Nanette Newman as the girl upstairs), an officious but kindly civil servant (Gerald Sim) and her wayward son Charlie (Ronald Fraser). Charlie sets the events of The Whisperers into motion, arriving unannounced and hiding a mysterious parcel in her flat. Although he only makes a fleeting appearance, Fraser gives his usual excellent performance, here instantly seedy, untrustworthy, trouble. Mrs Ross later receives a visit from a nosey social worker (Kenneth Griffith, another brief but excellent performance), which leads her to finding Charlie’s parcel – stolen money which she believes to be her inheritance.

The Whisperers has dated in how far a pound will go (at one point Mrs Ross loses a pound note and it is reported to the police), but is nevertheless still effective in showing how far the desperate might go to get their hands on the smallest of fortunes. Mrs Ross is plied with drinks by an unscrupulous woman and left unconscious by the side of the road by her husband (the fine character actor Michael Robbins from On the Buses). All for ten pounds. Miraculously, she survives the ordeal and another social worker (Leonard Rossiter – the brilliant cameos come thick and fast) tracks down her estranged (and, for the purposes of the plot, ten years younger) husband Archie. Archie Ross is more dream casting in the great Eric Portman, who portrays him with just the right mixture of resigned failure and last ditch ambition. Archie’s dream for the quick quid lead him, just like many of the others in The Whisperers, straight into oblivion.

Bryan Forbes has crafted an outstanding film that contrasts a dreamy mood piece personified by the hazy world of Mrs Ross with one that depicts a very sleazy picture of the 1960s. It’s a familiar one; dreary betting shops, petty gangsters in flashy cars and a craze of unrestrained and ruthless demolition serving as a backdrop (one of my favourite scenes is of Archie, working as a part time driver for a criminal gang, waiting by a demolished wasteland where only a small, single public house remains). The Whisperers was filmed at Pinewood Studios and on location in Oldham, Greater Manchester. Like Seance on a Wet Afternoon it makes excellent use of location resulting in, whether intended or not, a curious and fascinating period piece.

Unfortunately The Whisperers is not currently available on DVD, although it does feature in tv schedules from time to time and is well worth investigating for its cast of fantastic actors, of course for Edith Evans but especially for Eric Portman. And also to see the side of the sixties not often portrayed so desperately on film at the time; one that didn’t swing and didn’t revolve around a chosen London few.

GOLDBERG: Your wife makes a very nice cup of tea, Mr Boles, you know that?

PETEY: Yes, she does sometimes. Sometimes she forgets.

MEG: Is he coming down?

GOLDBERG: Down? Of course he’s coming down. On a lovely sunny day like this he shouldn’t come down? He’ll be up and about in next to no time. And what a breakfast he’s going to get.

By the end of the 1960s Harold Pinter was building an impressive record of film screenplays, including his collaborations with Joseph Losey (The Servant in 1963 and Accident in 1967), the Pumpkin Eater (1964) and The Quiller Memorandum (1966). Now already ten years old, his first full length play The Birthday Party was finally made for the cinema in 1968. It starred Robert Shaw as Stanley Webber. Shaw also appeared previously in The Caretaker (1963) making him perhaps the definitive interpreter of Pinter on film.

The Birthday Party has an interesting pedigree. It is directed by William Friedkin, who was later responsible for The French Connection and The Exorcist. Both of these energetic films are a stark contrast to what is essentially a faithful record of a claustrophobic stage experience. The film’s producers Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenburg were responsible for the run of first class horror films made by Amicus films in the sixties and seventies. The roles of Friedkin, Subotsky and Rosenburg are quite fitting; The Birthday Party is essentially a horror story.

The cast also includes Dandy Nicholls (from Till Death Us Do Part) as Meg Bowes, landlady of the sorriest of seaside boarding houses. She is superb, as are Sydney Tafler and Patrick Magee as Goldberg and McCann, the most menacing of house guests. Moultree Kelsall as Petey and Helen Fraser (Bad Girls) as Lulu complete the line up, and for anyone familiar with the play this is a very faithful version. There is a timeless quality about The Birthday Party, and whilst Friedkin’s direction (though mostly restrained) reveals some 60s indulgences (most notably in the opening sequence with the camera moving in on the wing mirror of Goldberg and McCann’s car and the backing soundtrack of ripping paper) Pinter’s dialogue does not date.

The Birthday Party offers various snapshots of haunting pasts, most disturbingly Stanley Webber and his vague portrayal of a former life. Although essentially a filmed play and little more (only Petey’s life as a deckchair attendant is seen fleetingly, chairs neatly and uniformly arranged), the performances are strong enough to hold the attention by merely suggesting what has happened in the past; here Stanley offering fragmentary snapshots culled from his mysterious history: his musical talent, its positive reception, the champagne that followed, his absent father:

STANLEY: I had a unique touch. Absolutely unique. They came up to me. They came up to me and said they were grateful. Champagne we had that night, the lot. My father nearly came down to hear me…. But I don’t think he could make it. No, I-I lost the address, that was it. Yes. Lower Edmonton.

Robert Shaw, an actor probably now best remembered for Jaws and his stint as a Bond villain, portrays this introspection perfectly.

Pinter’s themes of alienation, persecution and torture are vividly sketched out in The Birthday Party. Apart from Shaw, the other standout actor in the film is Sydney Tafler, who plays Stanley’s eventual nemesis Goldberg, a man who relishes his memories in the form of the anecdote. The refuge of the anecdote is the basis for Goldberg’s entire routine, this charming, smooth and potentially dangerous gentleman:

GOLDBERG: When I was an apprentice …my uncle Barney used to take me to the seaside, regular as clockwork. Brighton, Canvey Island, Rottingdean…we’d have a little paddle, we’d watch the tide coming in, going out, the sun coming down – golden days, believe me.

A stable past is personified by the kindly Uncle Barney, who Goldberg proceeds to describe as a well respected “impeccable dresser. One of the old school.” A pattern is very clear: the importance of place names that connect with memories, a figure from the past worthy of respect and admiration, usually the suggestion of a rose-tinted past, the faded “golden days”. If insecurity of the present needs such constant reinforcement, then the uncertain atmosphere prevalent in The Birthday Party unquestionably highlights this. Even Goldberg and McCann, Stanley’s interrogators, virtual torturers and eventual abductors, have their moments of uncertainty. Of all British cinema of the sixties, this film is the least assured of the supposedly bright decade.

Leslie Halliwell gave The Birthday Party only 1 out of a possible 4 stars and described it:

Overlong but otherwise satisfactory film record of an entertaining if infuriating play, first of the black absurdities which proliferated in the sixties to general disadvantage, presenting structure without plot and intelligence without meaning.

By 1968 Halliwell’s perceived golden age of cinema had already ended. Oddly, like the characters in The Birthday Party, he was stuck in the past.

Frankenstein Created Woman

As well as the essential M.R. James reading and viewing, Christmas is also a suitable time for a Hammer Horror. Hammer’s immensely successful 1957 film The Curse of Frankenstein spawned six sequels; The Revenge of Frankenstein (1959), The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Frankenstein Must be Destroyed (1969), The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974). Although the law of diminishing returns usually applies with film sequels, Hammer hit gold around the halfway mark. Frankenstein Created Woman is the best in the series, a classic chiller directed by Terence Fisher and featuring one of Peter Cushing’s best performances.

Frankenstein Created Woman is textbook Hammer, inviting the viewer to snuggle in front of the television under a cosy blanket. Unthreatening and warming, a well made film with recognisable settings, costumes, music and archetypal characters – all the familiar trademarks of the studio. That’s not to say that the film doesn’t look low budget by today’s standards. Its charm aside, the sets do look like they are ready to be folded away ready for the next production, and the costumes belong to the wardrobe that clothed the entire oeuvre of the studio. Even the rosé wine featured throughout this film that wasn’t drunk or spilt was probably carefully rebottled.

Nevertheless this is a horror film that has worn well over the decades. Frankenstein Created Woman is quite methodical in setting up its plot, reminding of The Curse of the Werewolf (1960) which has a similarly long preamble to the main story. It works very well here, and those who might find the early part plodding will be rewarded when things begin to fit together rather neatly towards the end. The film begins with a raving man being led to the guillotine. A small boy revealed to be the condemned man’s son is seen watching the execution, and when events jump ahead several years we see him again as Hans (Robert Morris), a young man in love with a disfigured girl called Christina (Susan Denburg). Hans works for Baron Frankenstein, who sends him out one night for a bottle of champagne following a particularly successful experiment (he has managed to be revived after freezing himself for exactly one hour. Yes, Baron Frankenstein always was a little weird).

As usual, Peter Cushing is superb as Baron Frankenstein, portraying the usual sharp wit and driven ambition that doesn’t quite tip him over into insanity. He is joined by Thorley Walters as his bumbling associate Dr Hertz. Walters plays a very baffled Watson to Cushing’s particularly sharp Holmes, and the two complement eachother quite perfectly throughout the film. Indeed, it’s a shame Hammer chose not to continue their partnership in the later films (Walters does turn up in Frankenstein Must be Destroyed but plays a different role). However it’s Cushing’s film and without his sublime acting it’s difficult to see how Hammer would have been so enduring and successful.

The quest for the Baron’s champagne sets things moving as Christina’s father happens to run the nearby inn. Three top-hatted scoundrels call in, the sort who are generally disagreeable in how they put their feet up on the tables and light smelly cheroots. Even worse, the type who demand their wine (to be put on credit) served by the innkeeper’s daughter. Their bullying turns nasty when Hans gets into a brawl with them and later, when the drunken trio return for some after hours drinking, Christina’s father disturbs them and they beat him to death. Hans is convicted of the murder and sent to the guillotine. Christina drowns herself. All a bit grim, but perfect for the Baron, whose latest experiment just happens to involve raising the dead. Together with Dr Hertz, he repairs Christina’s crippled body and, for good measure, implants the soul of Hans into it.

Susan Denburg is excellent as Christina in, surprisingly, the last of only a handful of film roles. This film does indeed create the type of starlet Hammer later used as a selling point for their films, the buxom young ladies employed for such titles as Lust for a Vampire and Twins of Evil. Resurrected by the Baron, Christina sets out on murdering the three top-hatted scoundrels who set the horrible ball rolling in the first place and this is all executed (pardon the pun) rather satisfyingly. And look out for Yes Minister’s Derek Fowlds as one of the above mentioned top-hatted victims.

The horror critic Alan Frank rated Frankenstein Created Woman quite highly in his 1982 Horror Film Handbook:

The last Hammer film to be made at Bray reworks Bride of Frankenstein to good effect. Fisher’s direction, impressive settings and a neat performance from Cushing make it a first-rate addition to the genre.

Frank also quotes a review from The Times:

Scriptwriter John Elder and director Terence Fisher have a nice sense of the balance between horror and absurdity and the film has the courage of its own lunatic convictions.

Surprisingly, other than mentioning that the film formed part of a double X double-bill with The Mummy’s Shroud in summer 1967, Hammer’s own celebratory 1973 The House of Horror has little else to say about the film. But perhaps it is time that has set Frankenstein Created Woman apart, where in a world now saturated with so many in your face explicit horror films we can recognise real quality.

Previous Page |

Next Page

With Walkabout and The Railway Children being enduring features of the television schedules, it’s odd that a far superior film starring the young Jenny Agutter is now totally forgotten. Made in 1969, I Start Counting was directed by David Greene and is a lost classic of British cinema. It’s one of the best depictions of that era I’ve seen on film; old buildings demolished for the New Town, quaint vehicles, short skirts and ugly shopping centres. It’s like a dose of late 60s Ken Loach but with the added spice of one of the more progressive Hammer films of the early 70s.

With Walkabout and The Railway Children being enduring features of the television schedules, it’s odd that a far superior film starring the young Jenny Agutter is now totally forgotten. Made in 1969, I Start Counting was directed by David Greene and is a lost classic of British cinema. It’s one of the best depictions of that era I’ve seen on film; old buildings demolished for the New Town, quaint vehicles, short skirts and ugly shopping centres. It’s like a dose of late 60s Ken Loach but with the added spice of one of the more progressive Hammer films of the early 70s.  Although The Whisperers boasts an excellent John Barry soundtrack, it sits far away from the usual Barry fare of stylish spy thrillers typical of the decade. Barry’s long partnership with Forbes (which included the similarly moody Seance on a Wet Afternoon) allowed him to compose for a different view of the 60s, one shot in stark black and white where the poor struggled on a meagre existence. Forbes depicts this in the early scenes of The Whisperers; a cold and miserable winter, the library full of the old as they huddle against the warm pipes, the needy shuffling along a line at the social services.

Although The Whisperers boasts an excellent John Barry soundtrack, it sits far away from the usual Barry fare of stylish spy thrillers typical of the decade. Barry’s long partnership with Forbes (which included the similarly moody Seance on a Wet Afternoon) allowed him to compose for a different view of the 60s, one shot in stark black and white where the poor struggled on a meagre existence. Forbes depicts this in the early scenes of The Whisperers; a cold and miserable winter, the library full of the old as they huddle against the warm pipes, the needy shuffling along a line at the social services.