Made in 1978, The Ice House is the final entry in the original run of the BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas series. A contemporary set, non M.R. James story and minus the directing talent of Laurence Gordon-Clark, this is perhaps the most far removed film from the original intentions of the annual seasonal treat. But like the disturbing Stigma from the year before, The Ice House still deserves a nod of recognition.

Where Stigma is harrowing to watch, The Ice House is effective by being chillingly weird. It was written by John Bowen, who also penned the cult Play for Today Robin Redbreast in 1970. In The Ice House John Stride is Paul, a man who visits a health spa in the country. He’s a lonely character, dropping into conversation that his wife has recently left him. There’s a generally odd air about the spa created by the almost unsettling calm of everyone and Paul becomes fascinated by the lightly incestuous siblings who manage the hotel and the eerie brick “ice house” out in the grounds. A suggestively shaped hole in his bedroom window also helps to add to his gradual feeling of chill.

The Ice House reminds of several other, and ultimately better, entries in the series, for example the gently macabre tone of Lost Hearts. There’s also the James theme of middle aged gentleman searching for and being drawn towards something evil, although this time it isn’t really clear what the motives are. And like all of the Ghost Stories for Christmas films before it, this one doesn’t end well for the protagonist.

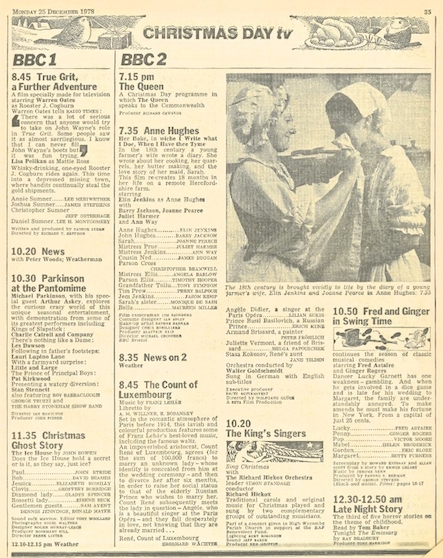

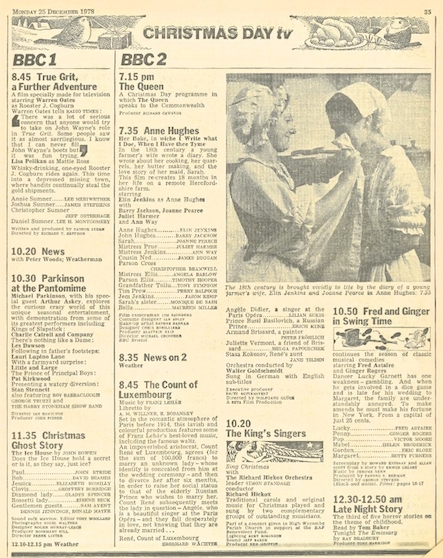

Christmas Day television ended transmission on BBC1 for Christmas Day Monday 25th December at 1135 pm with The Ice House. For an audience treated to an evening’s viewing of Mike Yarwood, True Grit: A Further Adventure with Warren Oates and Michael Parkinson talking to Arthur Askey it was probably a welcome relief. ITV offered an alternative with Ghost Story (1974) starring Larry Dann, whilst switching back to BBC2 at half past midnight offered the intriguing Late Night Story: Tom Baker reads The Emisary by Ray Bradbury.

And as for Lawrence Gordon-Clark, he moved over to ITV to direct a 1979 version of Casting the Runes starring Iain Cuthbertson and Jan Francis. Clive Exton (who wrote Stigma) adapted the original James story. This one is well worth catching.

The Tractate Middoth is the latest in the sporadic Ghost Stories for Christmas series, with Mark Gatiss adapting and directing this M.R. James story. Gatiss is a natural choice for the task – his accompanying documentary proved him a worthy student of James, along with his previous television ghost story credentials in his 2008 series Crooked House. This new M.R. James adaptation was broadcast on BBC2 on Christmas Day.

The Tractate Middoth is the latest in the sporadic Ghost Stories for Christmas series, with Mark Gatiss adapting and directing this M.R. James story. Gatiss is a natural choice for the task – his accompanying documentary proved him a worthy student of James, along with his previous television ghost story credentials in his 2008 series Crooked House. This new M.R. James adaptation was broadcast on BBC2 on Christmas Day.

The Tractate Middoth is familiar James material, with a secret will hidden inside a book located within a labyrinthine library. It’s guarded, naturally, by a dark spectre. When the book is taken and the will is discovered the thief is punished by supernatural means. There’s little more to it really, although Gatiss added some appropriate menace with the interior library scenes and did a fine job with source material that relies a little too heavily on coincidence. Roy Barraclough and Una Stubbs each provided comic turns in the drama. Although appreciated, it was slightly awkward as comedy isn’t really something that fits snugly into M.R. James. The cast also included Sasha Dhawan (fresh from his role in An Adventure in Space and Time), Louise Jameson, John Castle and David Ryall as root of all the ensuing evil, the hideous Dr Rant.

It’s difficult though to be critical as any new James adaptation is welcome. Rather like Doctor Who, it’s something I’d prefer to be there than not, although a late night showing on Christmas Eve may be the more fitting schedule. But hopefully the BBC will reinstate A Ghost Story for Christmas annually. I expect that Mr Gatiss will be up for it.

Stigma was the BBC’s 1977 Ghost Story for Christmas offering. This was a radical departure for the series with a new story by Clive Exton in a contemporary setting. The only link with the previous films is director Laurence Gordon-Clark, who explains in a DVD extra from the 2012 box set that the production team had exhausted all further options of M.R. James adaptations for budgetary reasons and hence looked towards new material. Stigma is often ignored and I’m not aware of it ever being repeated since the original transmission. I’ve had mixed feelings about the contemporary Christmas films (one more was to follow in 1978) and tended to ignore them myself. Stigma turns out to be a clever and disturbing piece.

Stigma was the BBC’s 1977 Ghost Story for Christmas offering. This was a radical departure for the series with a new story by Clive Exton in a contemporary setting. The only link with the previous films is director Laurence Gordon-Clark, who explains in a DVD extra from the 2012 box set that the production team had exhausted all further options of M.R. James adaptations for budgetary reasons and hence looked towards new material. Stigma is often ignored and I’m not aware of it ever being repeated since the original transmission. I’ve had mixed feelings about the contemporary Christmas films (one more was to follow in 1978) and tended to ignore them myself. Stigma turns out to be a clever and disturbing piece.

The 70s saw some bleak contemporary dramas, and many of the most memorable tended to involve menacing stone circles. Children of the Stones was a terrifying ITV children’s series from 1976, involving silent stones encroached upon by the modern world of motorways and ring roads. Three years later, the 1979 update of the long standing Quatermass depicted a society running down, with the Planet People, those who had rejected the modern world, drawn to the enchanting stone circle Ringstone Round. I’ve since been reminded of Alan Garner’s The Owl Service which was televised in 1969. Stigma is by far the least known of all of these but possibly the best effective drama of the three,

Full of subtle imagery, Stigma is a tale of blood, with the colour red running right through it. In the country cottage owned by Peter and Katherine, where they live with daughter Verity, there is blood red lingering from the glossy red front door of the house, through deep crimson nail varnish to a mouth watering red joint of beef – the colours seep through the film. Apart from this, Stigma is particularly understated – some snatches of Mother’s Little Helper and a glimpse of Their Satanic Majesties Request (Rolling Stones – geddit?) notwithstanding, there is no soundtrack at all.

The film is just half an hour long so it’s quick in execution. Arriving home, Katherine and Verity observe two workmen as they attempt to remove a huge stone from their garden, part of Peter’s plans to extend the path from the cottage. Beyond, in the next field, other stones linger eerily. A gush of wind breezes over Katherine. The stone is only partly shifted, and what follows is a horrible descent into her demise as she begins to slowly bleed. Peter arrives home but is oblivious to her plight, only noticing red wine on her dress. At least the beef is delicious. Verity remains an ambiguous presence to the end.

The cast is excellent. A prior To the Manor Born Peter Bowles, reminds what a decent actor he is, and Kate Binchy and Maxine Gordon as Katherine and Verity are also superb. What’s most effective about Stigma is Katherine’s attempt to hide the developing catastrophe, and her frantic efforts to do so are extremely effective. Binchy is very convincing in the role. But perhaps too much so – Stigma may not have been well received at the time because it strays far into the horror genre (I’ve filed it as such) much more than the fireside, port sipping territory of M.R.James. This is a shame, and maybe being produced independently from A Ghost Story for Christmas would have given it a greater legacy.

I’ve been writing annual reviews of A Ghost Story for Christmas for eight Christmases now. This is perplexing as the original series also ran for eight years and I’m yet to review the last – The Ice House. Spooky. 2013 sees another revival, with Mark Gatiss’s version of The Tractate Middoth. I’m really looking forward to it. Long may the series live.

The Ash Tree was the BBC’s 1975 Ghost Story for Christmas. It is perhaps the most unusual of their M.R. James adaptations.

Unlike the others in the series, The Ash Tree offers the least in seasonal fireside comfort viewing. Where the memory of the BBC M.R. James films invite memories of a comfortable supernatural tale, foolish men meddling with treasure and so on, The Ash Tree is decidedly strange and stands out as a stark entry, particularly in the use of location shooting.

The Ash Tree was first broadcast on 23 December 1975 at 11.35. Directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, Edward Petherbridge takes the lead as Sir Richard Castringham, who has recently inherited a country seat with an unfortunate history. The house has been cursed since the day his ancestor, Sir Matthew, condemned a woman to death for witchcraft. It is soon discovered that the ancient ash tree outside his bedroom window is the root of the problem.

The Ash Tree was first broadcast on 23 December 1975 at 11.35. Directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, Edward Petherbridge takes the lead as Sir Richard Castringham, who has recently inherited a country seat with an unfortunate history. The house has been cursed since the day his ancestor, Sir Matthew, condemned a woman to death for witchcraft. It is soon discovered that the ancient ash tree outside his bedroom window is the root of the problem.

Petherbridge is very good as Castringham, and the film is fairly horrific and impressive for the BBC budgetry considerations at the time. Particularly vivid are the ghoulish creatures that pour out of the tree on Castringham’s last fateful night.

Although I’ve yet to review the two modern day Ghost Story for Christmas entries, Stigma and The Ice House from 1977/8, I feel my job is really done here. But it’s quite comforting that after six years of writing about M.R. James on the BBC my wishes have finally come true with the recent release of the entire series on DVD. The collection has some excellent extras, including introductions by Laurence Gordon Clark. Most interesting though is the booklet of essays which point towards other supernatural anthology series of the time. Most notably there is Dead of Night from 1972 and Out the Unknown which ran from the mid 60s until 1971. Some, but only a few, episodes survive from them but are available on YouTube. I’ll be reviewing some soon. I’ve also rediscovered the BBC series West Country Tales from 1982. having watched several episodes I’m happy to report that it’s rather excellent and will keep me going in ghostly review for some time to come!

Incidentally, Lawrence Gordon Clark jumped the comfortable BBC ship in 1979 to direct a version of M.R. James’ Casting the Runes which also featured Edward Petherbridge, along with Jan Francis and Iain Cuthbertson. Worth investigating.

“Halloa! Below there!”

In 1976 the BBC moved away from their usual ghostly M.R. James Christmas offering. Instead, on 22nd December that year, they screened an adaptation of The Signalman by Charles Dickens. The Signalman is perhaps one of the all time classic ghost stories. Dickens excels in the genre but this is also a brilliant film; a demonstration of how low budget, atmosphere, great writing and performances can create something truly magical.

Denholm Elliott as the troubled and ultimately doomed signalman is possibly the greatest asset of this production. Elliott is magnificent, perfectly capturing the edgy and nervous man, condemned to dull, repetitive – yet very important – tasks in his solitary employment. So horribly haunted – he’s actually quite painful to watch at times.

Denholm Elliott as the troubled and ultimately doomed signalman is possibly the greatest asset of this production. Elliott is magnificent, perfectly capturing the edgy and nervous man, condemned to dull, repetitive – yet very important – tasks in his solitary employment. So horribly haunted – he’s actually quite painful to watch at times.

Elliott is an actor perhaps not immediately thought of alongside the supernatural, although when you dig there are some gems. Most notably there is his appearance in Hammer’s To the Devil a Daughter (1976) and their tv classic Rude Awakening from 1980, Vault of Horror (1973) from Amicus and some obscure appearances in Mystery and Imagination in the late 60s (as Dracula) and the other tv appearances Supernatural in 1977 and The Ray Bradbury Theatre in the late 80s. But extending this list any further may suggest that Elliott was at times a jobbing actor. The Signalman, however, proves his immense talent.

Returning to our 1976 Dickens adaptation, the signalman of the title is troubled by ghosts, each of which has delivered a grim portent. He’s haunted terribly in his lonely employment. The first ghost warns of an awful collision in the tunnel nearby. The second of a young bride falling from a train. Both of these warnings come true, with the signalman a witness to the terrible events. The third tragedy is suggested by a visiting spirit covering its face, waving one arm and repeatedly calling “Halloa! Below there!” The signalman mistakes a traveller – who calls out these very words to him – for the ghost, and nervously invites the stranger (played by Bernard Lloyd) into his signal box. He recounts his tales to him, his attention often snatched by his solemn duties.

Ghost Story for Christmas director Lawrence Gordon Clark works up the menace wonderfully and the adaptation is written by Andrew Davies, who tackled both Bleak House and Little Dorrit thirty or so years later. The Signalman offers a cosy sort of terror, with the traveller mostly bemused by the odd railway worker until the eventual tragedy strikes, where the third and final terror strikes on the poor signalman himself. I think, however, by then it was a blessed release for him.

Although still a classic to watch, it’s probably not wise to look into the story too deeply. For example, why his employment is continued after witnessing multiple tragedies in the same small stretch of railway. Why didn’t his line manager look closely at health, safety and well being issues? Or at least grant the poor man a spot of annual leave. And so on. But remember, this is Ghost Story for Christmas time. Soak up the atmosphere. Believe.

“He was cut down by an engine, sir. No man in England knew his work better. But somehow he was not clear of the outer rail. It was just at broad day. He had struck the light, and had the lamp in his hand. As the engine came out of the tunnel, his back was towards her, and she cut him down. That man drove her, and was showing how it happened. Show the gentleman, Tom.”

The man, who wore a rough dark dress, stepped back to his former place at the mouth of the tunnel.

“Coming round the curve in the tunnel, sir,” he said, “I saw him at the end, like as if I saw him down a perspective-glass. There was no time to check speed, and I knew him to be very careful. As he didn’t seem to take heed of the whistle, I shut it off when we were running down upon him, and called to him as loud as I could call.”

“What did you say?”

“I said, ‘Below there! Look out! Look out! For God’s sake, clear the way!’”

Previous Page |

The Tractate Middoth is the latest in the sporadic Ghost Stories for Christmas series, with Mark Gatiss adapting and directing this M.R. James story. Gatiss is a natural choice for the task – his accompanying documentary proved him a worthy student of James, along with his previous television ghost story credentials in his 2008 series Crooked House. This new M.R. James adaptation was broadcast on BBC2 on Christmas Day.

The Tractate Middoth is the latest in the sporadic Ghost Stories for Christmas series, with Mark Gatiss adapting and directing this M.R. James story. Gatiss is a natural choice for the task – his accompanying documentary proved him a worthy student of James, along with his previous television ghost story credentials in his 2008 series Crooked House. This new M.R. James adaptation was broadcast on BBC2 on Christmas Day. Stigma was the

Stigma was the  The Ash Tree was first broadcast on 23 December 1975 at 11.35. Directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, Edward Petherbridge takes the lead as Sir Richard Castringham, who has recently inherited a country seat with an unfortunate history. The house has been cursed since the day his ancestor, Sir Matthew, condemned a woman to death for witchcraft. It is soon discovered that the ancient ash tree outside his bedroom window is the root of the problem.

The Ash Tree was first broadcast on 23 December 1975 at 11.35. Directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, Edward Petherbridge takes the lead as Sir Richard Castringham, who has recently inherited a country seat with an unfortunate history. The house has been cursed since the day his ancestor, Sir Matthew, condemned a woman to death for witchcraft. It is soon discovered that the ancient ash tree outside his bedroom window is the root of the problem.  Denholm Elliott as the troubled and ultimately doomed signalman is possibly the greatest asset of this production. Elliott is magnificent, perfectly capturing the edgy and nervous man, condemned to dull, repetitive – yet very important – tasks in his solitary employment. So horribly haunted – he’s actually quite painful to watch at times.

Denholm Elliott as the troubled and ultimately doomed signalman is possibly the greatest asset of this production. Elliott is magnificent, perfectly capturing the edgy and nervous man, condemned to dull, repetitive – yet very important – tasks in his solitary employment. So horribly haunted – he’s actually quite painful to watch at times.