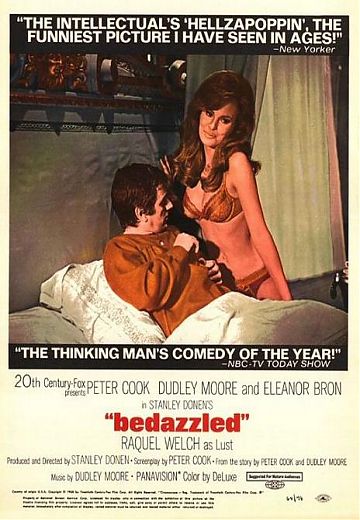

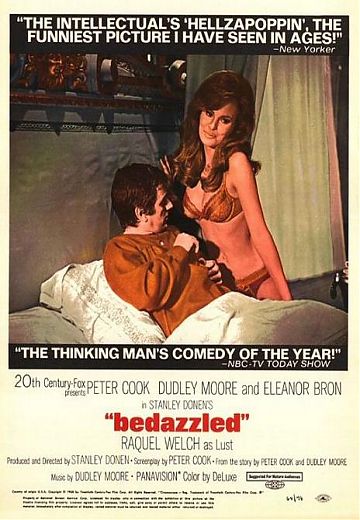

In 1967, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were the BBC’s shining comedy stars. It’s difficult to judge now just how popular they were thanks to the Beeb’s crazy decision to wipe the tapes of most of their Not Only, But Also series. As a team, Cook and Moore’s achievements are now best marked by the few sketches that do remain from the black and white shows and from the cult Derek and Clive recording that came much later. Peter Cook is now probably best remembered for, well, simply being Peter Cook – amusing and often tipsy on numerous chat shows. But 1967 was also the year of their finest achievement. The brilliant comedy film Bedazzled.

Typically for a 60s upgrade from television to film, Bedazzled is colourful, expensive and made to last. Perhaps Cook and Moore were aware that their television exploits were soon to be binned (rumour has it that Peter Cook wrote begging letters to BBC chiefs in the early 70s to save his old shows from the skips lined along Wood Lane), and wanted some cash thrown at their talent. But unlike many comedy films adapted from tv in the 60s, and especially 70s, Bedazzled is far above average. This is possibly because, different to the situation comedy, Cook and Moore’s humour was sketch based. But unlike Monty Python’s lazy And Now For Something Completely Different, which simply refilmed a series of television sketches for the big screen, Bedazzled creates an interesting and inventive frame for the sometimes unrestrained humour.

Moore plays Stanley Moon, a hapless cook in a Wimpy bar, besotted by a waitress (played by Eleanor Bron). He meets a George Spiggott (aka The Devil – Peter Cook), who grants him a series of wishes in order to allow Stanley to win his girl. This is the framing device, and Cook (who wrote the screenplay) creates a way to easily weave together what is essentially a series of short sketches. Some of them don’t work so well, although the ones that do are hilarious (Moore as a raspberry blowing trampolining nun is the funniest thing they ever did together). It’s all far from the satire often associated with Cook’s humour, although when he does attempt it – such as the spoof of 60s bands – it’s brilliantly spot on.

Bedazzled sometimes comes across as a film that’s been engineered to look like it belongs in the swinging 60s. There are the glimpses of routemaster buses and red post boxes, and what always fascinates me about films made in London in this period is the locations. Bedazzled depicts London as half building site half modern office block (the Post Office Tower features heavily in one scene). And oddly, like most of the location shooting from tv’s The Avengers, the streets are empty and devoid of extras and traffic. London is depicted as eerily empty and hassle free. In one scene Cook and Moore pretend to be traffic wardens, although the pre-congestion charge London of 1967 looks like a city where parking is never a problem.

It’s worth seeing Bedazzled for a record of Cook and Moore at their peak, before the respective boozing and lure of Hollywood got in the way. Raquel Welsh also makes a cameo appearance, as does Barry Humphries, and Moore wrote the theme music. Possibly it’s tongue-in-cheek music, but it’s as good as anything from similar films of the period. Just watch out for the migraine-inducing effects that accompany the opening titles. Incidentally, it’s directed by Stanley Donen who’s probably best known for Singin’ in the Rain.

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore went on to appear together in the films Monte Carlo or Bust and The Bed Sitting Room, both made in 1969, although these were more ensemble pieces. The first a caper movie, the second more of a Spike Milligan vehicle. In 1978 they got back together for the coarser-humoured Hound of the Baskervilles. As a solo performer, Cook appeared in several films including the spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic (1968) and The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer (1970) which he co-scripted with John Cleese. But he was never much of a varied actor, and Moore was left to pursue a much more successful, if ultimately irritating, film career. Bedazzled is by far the best thing both of them were involved in on the big screen. The script is very well written and it’s a witty and, most of all, a very charming film. And a reminder that they were a very charming and likeable double act.

You might think that wanting to read Paul Auster’s Man in the Dark because it was such a short novel is an odd reason for choosing a book. Perhaps you are right, but after listening to the author being interviewed I was intrigued to find out how he managed to pack to many interesting ideas into something so brief.

You might also describe the night hours that one spends sleeping as also brief; not so if you are an insomniac like August Brill. Recovering from a car accident (and, indirectly, recovering from the brutal murder of his grand-daughter’s boyfriend), Brill lies awake at night, inventing stories to while away the hours and prevent himself from addressing stark reality. Auster’s premise is an alternative America, a country where there was no 9/11, subsequently no war in Iraq – Brill sketches out in his waking dream a second US civil war. He invents his own hero, a man called Brick, who wakes up in this weird alternative world. The premise works wonderfully. As a fantasy in the mind of a sleepless narrator it is perfectly justifiable and believable. Eyes wide open, I found myself caught up in Brick’s plight.

Auster switches between the imagined narrative and Brill’s more sober existence. We slowly learn about his life and his relationship with his bereaved grand-child. The two spend hours watching classic films, and there’s an interesting meditation on the relationship between novels and the cinema, and some excellent criticism of European films. But just as things begin to fit into a comfortable rhythm Auster does something unexpected – he kills off his invented hero. Goodbye Brick. It’s so shocking, possibly as shocking – to compare an artist from the world of cinema – as Hitchcock killed off Janet Leigh halfway into Psycho. This turns Man in the Dark from a quirky novel that flirts with science fiction into something more thought provoking.

Despite Auster’s bold move I did feel let down. Secretly, I want neat and resolved endings. At least a conclusion of the absurd premise I’ve been given. Brick, in the alternative US, is ordered to kill Brill in the real universe. A sort of “kill the author, save the world”. But Auster isn’t interested in neat endings, and wants us to be reminded of the sometimes horrible world we’re stuck with, with means him delivering a final, and disturbing, incident from the Iraq war. This is a novel I will have to read again. While Auster is keen to offer an alternative world he’s sketchy about how we got there. He’s also unclear that if you remove horrors from recent history the outcome isn’t necessarily preferable. It’s a book of paradoxes. And it will probably keep you awake.

Trois Histoires Extraordinaires d'Edgar Poe

Also known variously as Histoires Extraordinaires, Spirits of the Dead, Tales of Mystery, Tales of Mystery and Imagination and – sigh – Tre passi nel delirio, this extraordinary film is the result of what happened when they asked three leading European directors to collaborate on the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Roger Vadim, Louis Malle and Federico Fellini each contributed a tale to this 1968 gem. It’s difficult to decide which of the three segments is the most confusing, infuriating and visually stunning. They are all in turn weird and complex, and feature a top notch cast including Jane and Peter Fonda, Alain Delon, Brigitte Bardot and Terence Stamp.

Thinking of Poe adaptations, Roger Corman’s series of films from the early 1960s featuring Vincent Price always springs to mind. This film is nothing like that, and the adaptations – especially the Fellini one – are painted with very broad brushstrokes. It’s also very much a film of its time, and its cast – especially Fonda and Stamp – icons of that era. Roger Vadim and Jane Fonda appear to be gently warming up for Barbarella and their section Metzengerstein, that opens proceedings, doesn’t really amount to much. It’s visually very impressive, with an medieval and semi-erotic theme to it (what more do you need?) but the story is too vague and open-ended. Jane Fonda plays a woman who appears rude and cruel to all who she encounters, until her cousin saves her from an animal trap in the forest. He’s later killed saving a horse from a fire, and following this both a strange tapestry and a beautiful black horse appears. There’s a jolt of a scene when we finally get to see the completed tapestry, although other than that it lets down somewhat.

Things pick up with the second section, William Wilson, which stars Alain Delon as a man haunted by his namesake, the other William Wilson who trails him throughout his life. It begins with a fantastic scene of Delon running towards a church, desperate to confess his sins. We learn of his childhood and life as a medical student, and there is an extraordinary and terrifying scene involving an attempted live dissection. Ouch! Unfortunately it then sags in the middle. Brigitte Bardot appears wearing an absurb black wig and the two become involved in a long and convoluted card game, Delon’s wooden acting not helping very much. William Wilson ends rather predictably, but Louis Malle’s direction keeps it interesting and he injects equal proportions of charm and menace.

The third section, Toby Dammit, is the best and this is where things really do take a weird turn. In Fellini’s piece, Terence Stamp plays a boozy and bored looking British actor who is lured to Italy on the promise of a Ferrari to make a Western. This is very much a perfect role for Stamp, with his unruly hair dyed blond I freely have to admit that he was a very handsome young man indeed, despite the fact that he also looks completely washed out and wasted in this movie. He also plays on a childlike charm he used very effectively in Billy Budd and again much later in The Hit. Here, dubbed into Italian, he resorts to odd movements and mannerisms. Perhaps he was unfamiliar with the language, although this would be sometimes incomprehensible in any tongue. At times he’s almost clown like, at others robotic, and if the boredom and indifference he conveys is any comment on his own – sometimes charmed – life at the time then it certainly had an affect on his future. Like his contemporary James Fox (who took his role in Performance a little too far), Stamp also baled out of acting for a few years at the end of the 60s. And seeing Toby Dammit makes me think making this film might have contributed to causing his lost years.

Toby Dammit is odd like you’d expect Fellini to be. Odder in fact, although it does get bogged down with its hero driving his Ferrari like a madman and screaming. Only when, like the preceding tales, it moves into proper Poe territory does it really grip and Stamp’s eventual nemesis in the shape of a small and seemingly innocent child really sent a chiver down my spine. But what it’s all really about – well, you really need to see this for yourself. It didn’t help that I watched the whole of this in fifteen chunks on YouTube and it’s possible I may have got a couple of the Stamp segments the wrong way round, although I’d imagine Fellini would be amused by this. All three of the tales are linked, albeit casually, and explore three not particularly likeable individuals and how they bring about their own ends. Weird, yet certainly mysterious. And definitely extraordinary.

Previous Page |

Next Page