As usual, we sat down to watch Jurassic Park the other evening. It’s a classic, although I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen it. There does appear to be a mismatch between the films repeated endlessly on tv and the films rarely, or never, shown. So here’s some of the very obscure films I’d like to see. They are oddball films.

Oldies

Yes The Times are giving away DVDs this week for some of Alfred Hitchcock’s 30s films. All brilliant, but what about his really early films? What about The Lodger (1927) and his other silent films?

Horror

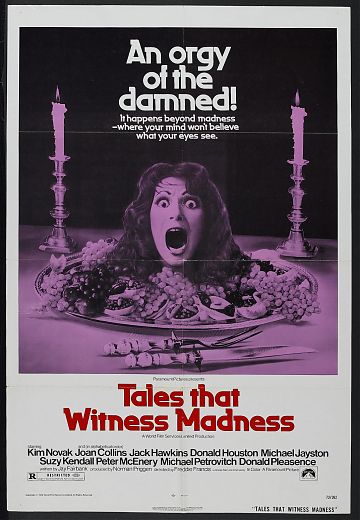

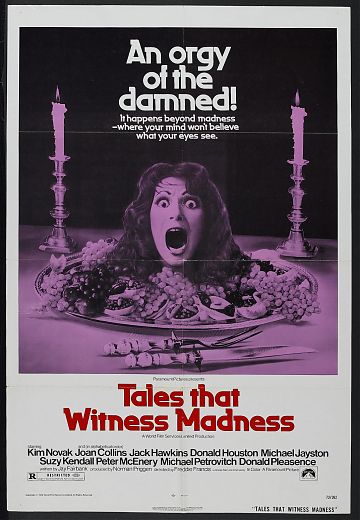

An endless list. How about The Skull (1965), a very creepy Peter Cushing film. You can catch the 1974 Amicus portmanteau Vault of Horror quite regularly, but how about Tales that Witness Madness from 1973? Then there’s Hammer, who made a series of psychological horrors in the 1960s. A couple of them, such as Paranoiac (1963), feature Oliver Reed. Here’s an actor who, up until his last celebrated film Gladiator (2000), acted in obscure films for years. He wasn’t in the pub all the time as rumour may have it, just look at Reed’s list of films.

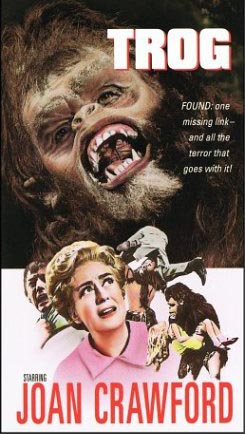

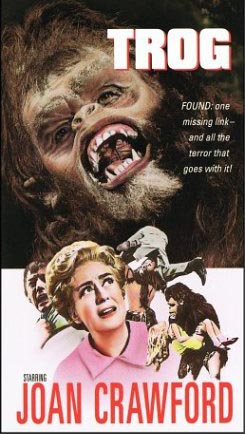

Denis Gifford’s A Pictoral History of Horror Movies has some films so obscure that I forgive you for thinking I’ve made them up. Mad Doctor of Blood Island (1970), The Phantom of Soho (1963) and Joan Crawford in Trog (1970) for example. Trog deserves a special mention.

In her last film, Crawford plays an anthropologist who unearths a troglodyte (an Ice Age ‘missing link” half-caveman, half-ape) and manages to domesticate him – until he’s let loose by an irate land developer (Michael Gough). Alas, I’ve never seen it but I would imagine Gough to be suitably insane. He certainly is in Konga (1961) and Horror Hospital (1973).

Weirdly

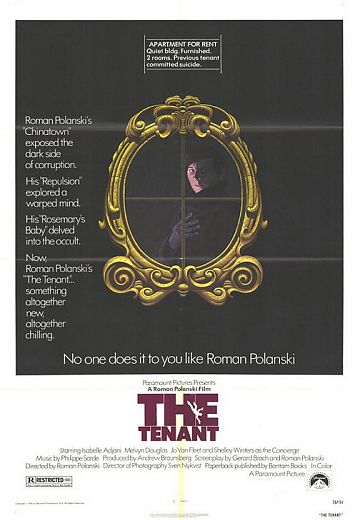

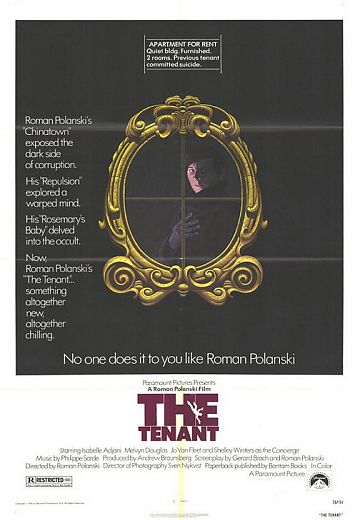

You’ll only catch Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (1976) on DVD. Cul-de-sac (1966) sometimes gets an outing, but his 1972 sex comedy What? doesn’t. It’s the only film directed by Polanski that I’ve never seen and it irks me. Macbeth (1971) is easy to obtain on DVD, as is the disappointing but worth catching The Ninth Gate (1999) starring Johnny Depp.

Everyone knows The Wicker Man (1973) but have you ever seen director Robin Hardy’s only other film The Fantasist (1986) ? I did, at the time, and remember it being great.

Comedy

Harold and Maude (1970) has vanished from view. As have many more popular American comedies from the early 70s. There was a time when films featuring Alan Arkin were never off the telly. But I’ll save the comedy for another day.

Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers directed a film in 1968 called Mr Topaze. Legend has it that the mad Mr Sellers burnt all of the negatives. This makes it possibly one of the most rarely seen films ever. He made many other obscure films during his career. The Blockhouse (1973) is one of them, where he co-starred with Charles Aznavore. They play allied POWs who become entombed in a concrete bunker that’s stocked with provisions to last them several years. What’s happened to this film? Has it been entombed as well?

Terence Stamp

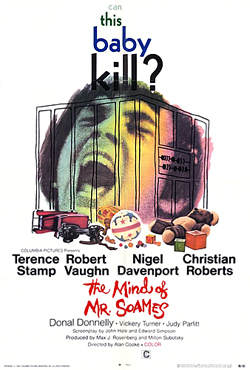

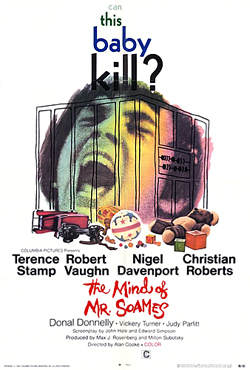

The veteran actor has been appearing in oddball films for nearly 50 years. The Collector (1965) is shown very rarely, and I’ve never seen the sci-fi tinged The Mind of Mr Soames (1970) or Hu-man (1975) at all. What about the Uri Geller biopic Mindbender (1996) or the strange monkey film Link (1986)? Easier to find are the deliciously oddball Elektra (2005) and Revelation (2001). He’s still at it; the prolific Mr Stamp has eight films in production in 2008. Good luck to him, although some of them sound very odd indeed.

David Hemmings

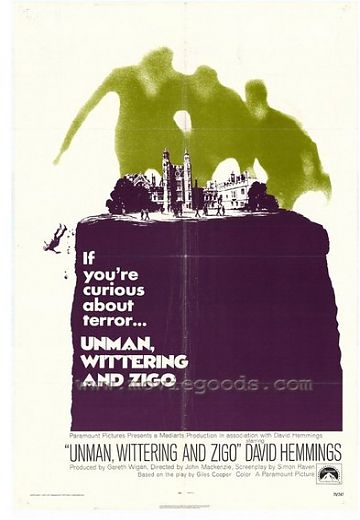

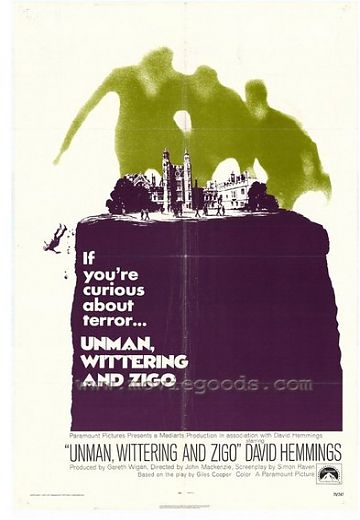

Another British actor who made many obscure films. The late Mr Hemmings appeared in Voices (1973) and Unman, Wittering and Zigo (1971). I’ve seen them both, although not for years and years. Rather than research them, I’ll just recall from memory that they were very odd and captivating films. The first, which I remember seeing in an afternoon slot, was about two people who have seemingly survived a car accident, holed up in a strange house in the country. The second was about a schoolteacher, subtly tortured by his unruly class.

60s films

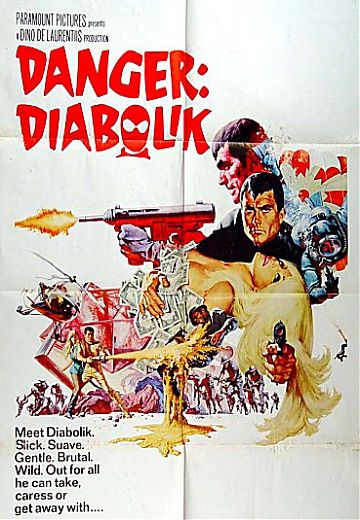

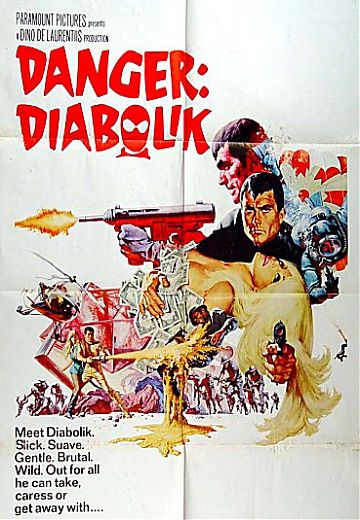

Modesty Blaise (1966), another Terence Stamp oddball effort, turns up occasionally, although similar films from the period don’t turn up at all. Diabolik (1969) is a similar but much better film than Modesty Blaise.

Richard Lester made a film in 1968 starring Julie Christie called Petulia. And talking of Ms Christie, Darling (1965) has kind of disappeared from the radar.

Enough to be going on with then. One day I’ll track down my oddball films; searches for Mr Soames on YouTube return sobering footage of the MP Nicholas Soames. Although the whole of Unman, Wittering and Zigo is there in all its unadulterated glory! I’m off to enjoy…

Call me unusual, but I found Tom Rob Smith’s Child 44 perfect summer reading. Although large and cumbersome, the hardback edition was always high on the list when packing our beach kitbag, and it always went in alongside the crocs, bucket and spade and water bottle. Smith’s debut novel has received a lot of attention for being part of the 2008 Booker longlist and, uncharacteristic for the Booker, being a thriller. This is also a novel that takes many thriller conventions (a serial killer, a wrong man chase) and wraps them up in the setting of 1950s Russia. The biting cold, the fear of being turned in by one’s own family, the torture and confession. Yes, it all made gripping summer reading.

Leo Demidov, a state security agent, is called in to pacify a family who are pleading that their young son has been murdered. The official line is that there was an unfortunate accident, and that murders are simply not commited in the neat and tidy climate of Communism. Leo is happy to go along with this, although the family concede through reasons of fear rather than reliable evidence. Leo returns to his day job, pursuing and apprehending the latest in a long line of suspect traitors. Although he pleads his innocence, the arrested man is routinely tortured for a confession and executed. What follows is one of the many fascinating twists of this novel, where one of the names provided by the tortured man is Leo’s own wife. Is she a suspect? Is Leo being punished for taking too much of an interest in the accidental death of the child? Is this the revenge tactics of a fellow officer? Leo is subsequently ordered to investigate his wife’s movements and what follows is a very well constructed and memorable episode, where he follows her on the network of Moscow’s underground, himself being followed by another agent. It’s pure Hitchcock, and I imagine that the film rights for this novel are already in someone’s eager hands. Just don’t cast Tom Hanks.

But what’s happened to the murder story? you may be asking , although Smith doesn’t rush with the serial killer thread and is more intent in the first half of the novel to establish character and setting. When Leo is demoted after failing to denounce his wife (although she remains at this stage an ambiguous character) and the Demidovs are relocated to a slum town outside of Moscow another victim is discovered, and Leo slowly finds out that the original death he was asked to sweep aside was a murder and was one of many. Child number 44. Cranked up to a reasonable tension, the novel then descends into more obvious territory, part James Bond escapes (a memorable one from a moving train, a less convincing one involving a car chase), part gut churning forensics (both in murder and interrogation victims). At times Smith is too keen to tie up all of the loose ends. He’s even cheeky enough to set things up for a sequel. But I found Child 44 above average for a thriller, and Smith just about gets away with the preposterous explanation for the sequence of murders and their connection with Leo. For me the book gained strength from the atmosphere of distrust and suspicion it creates, perhaps something of a cliché for a depiction of Stalinist Russia although he’s careful not to go too far with this. Leo Demidov is also interesting as the flawed lead, and Smith pulls the reader towards the plight of a man who’s done some terrible deeds, and made some awful decisions, in his past. What didn’t work so well for me was the frantic conclusion, although the final twist is delivered with some aplomb. It may be a ridiculous and far fetched premise, but Smith carries it off rather well.

So this was the novel that, albeit temporarily, broke my book buying ban. Some critics have been harsh, perhaps because of the Booker connection, but I really, really enjoyed this and recommend it for all. So there. It was a worthy relapse from the book buying, and I fully expect next year’s beaches to be awash with the paperback edition.

All Quiet on the Western Front

Wednesday August 27, 2008

in books read 2008 |

I feel agitated; but I don’t want to be, because it isn’t right. I want to get that quiet rapture back, feel again, just as before, that fierce and unnamed passion I used to feel when I looked at my books. Please let the wind of desire that rose from the multi-coloured spines of those books catch me up again, let it melt the heavy, lifeless lead weight that is there somewhere inside me, and awaken in me once again the impatience of the future, the soaring delight in the world of the intellect – let it carry me back into the ready-for-anything lost world of my youth.

I sit and wait.

For a reader weaned on Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong and Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, I’ve put off All Quiet on the Western Front until now. Erich Remarque’s 1929 anti-war novel has escaped me for only the foolish belief that I didn’t need to read another First World War novel. I was wrong.

All Quiet on the Western Front is particularly potent for being a German anti-war novel, suggesting why many are drawn towards joining the army for the rewards of superiority it can give, personified in the story by Remarque’s bullying drill sergeant. The novel hints that dominant behaviour is an ugly and contagious part of human nature, one of the reasons why the Nazis were probably intent on burning the book; actions which then led to the author’s subsequent exile. As a young German soldier drawn to enlist with his fellow classmates mainly at the insistence of their schoolteacher, the fictional character Paul Bäumer narrates this absorbing, harrowing and thought provoking book. His nationality and the side he fights for matters not; as Bäumer quickly realises, there is no clearly defined enemy in the insanity of trench warfare. But that a German writer has produced such a powerful work makes it all the more poignant.

Remarque served in the First World War, although this novel is only partly autobiographical. He spent some time in a military hospital, and the scenes where Bäumer is treated are particularly convincing. The bloodshed of the battlefield is as upsetting as you might expect, and I found the realism of these scenes particularly disturbing for a novel written in 1929. Not because this is little more than a decade after the events took place, but because the writing is fresh, modern and full of grim insight. Bäumer and his friends discuss the reasons for the conflict they are trapped in but come to no conclusions. They don’t really understand the reasons why they were fighting that war. I certainly don’t really grasp why the First World War was fought either. Do you?

All Quiet on the Western Front goes much further than just graphically depicting the horrors of war. The quotation I’ve opened with is from Bäumer’s spell of leave, where he visits his family home. Sitting in his room, he realises how the war has removed him from the true, free living individual he once was. He has no interest in picking up the books that once absorbed him. It’s a very moving and sad scene. There’s also several passages where Remarque dwells on the unkindness between supposedly fellow comrades. Returning to the character of the bullying drill sergeant, he follows Bäumer and his friends as they lie in wait for and subsequently beat up the man who has made thier lives a misery. They feel refreshed and vindicated; Remarque leaves it up to the reader to decide if their actions are justifiable. Similarly, another friend of Bäumer’s is placed in charge of a Home Guard platoon to discover the very teacher who urged his pupils to go to war amongst his ranks. More ritual humiliation follows, and again Bäumer and his peers see it as fitting treatment.

Although this is a novel that fiercely opposes war, it is knowing enough to question the contradictions of human nature and ends on a sour note when Bäumer concedes that the generation following his will quickly forget the 1914-1918 war, or at least find its imprortance muted. There is a particularly telling episode where, seperated from his allies and taking refuge in a shell hole in no-man’s-land, he stabs to death a French soldier to save himself. He’s mortified by his actions, attempts to save the dying soldier, eventually mulling over the contents of the corpse’s wallet. This doesn’t last long; self-preservation takes over and Bäumer realises he must forget the identity of the dead soldier and return himself safely to his trench. Life goes on. The impatience of the future.

Previous Page |

Next Page