Sometime in New York City

Yet even at that tender age, he glimpsed ‘the little child inside the man’, to quote one of John’s last pieces of self-analysis. ‘I remember that Alice, our black cat, had jumped out of the window after a pigeon and died, and I remember that was the only time, I think, I ever saw my dad cry.’

Ah, the terrible inevitability of coming to the end of a Lennon biography. Following the Beatles break up in 1970 the following ten years just whizz by; heroin, primal scream therapy, the move to New York, the political sloganeering, the lost weekend, the birth of Sean and John’s retirement. The Double Fantasy comeback and finally…

Philip Norman pieces together Lennon’s last years better than any other biographer in this, the end of John Lennon: The Life. In 1975, following the birth of Sean, John Lennon decided to walk alway from the music business as his recording contract coincidentally ended in the same year. He chose not to renew it, enjoying as he would later put it, the life of a house-husband, almost pioneering the role reversal of husband at home and wife at work. Baking bread, singing lullabies, bliss. Norman, however, reveals that Lennon was far more active than other accounts have let on. As well as extensive travelling (several visits to Japan, and a sailing holiday in the Bermuda Triange) he had fleeting contact with Paul McCartney and the two were to meet, if not frequently, but had a less estranged relationship than we might believe.

In the late 70s a US comedy show challenged John and Paul to revisit the studio to stage a reunion. Not only was an amused Lennon watching at home in the Dakota, but McCartney was sitting with him, and the two almost called a taxi to take up the dare before eventually abandoning the idea. At other times in this period the Beatles came close to reforming; as well as tempting financial offers John and Paul once played to a substantial audience at a beach party, and Lennon continued to write and demo songs in this supposed quiet period, one of which became Free as a Bird.

Norman’s final chapters are beautifully written, almost moving, as Lennon finds the peace that eluded him through most of his life (even when he was demanding that peace be given a chance). As the inevitable end comes into view, he draws the story to a conclusion without dwelling on the aftermath of his murder and his legacy since then. Instead the book closes with a meeting between Norman and Sean Lennon. Only aged five when his father died, his memories are obviously hazy, but this makes from a memorably impressionistic account of the man, the dad who sometimes lost his temper but who cried when the family cat died.

John Lennon: The Life gives a believable snapshot of the man’s state of mind when he died. Enthusiasm for what the future held (further recording, a planned trip to England) was tinged with the Beatly past he couldn’t quite shake off – the awkward presence of Paul in the world (his rival forever), continued friendship with the ever-amiable Ringo and growing resentment towards George Harrison (who chose to barely mention Lennon in his own autobiography). And a strangely unkind disregard for the brains behind the scenes, George Martin. If he couldn’t quite escape the Beatles, I still read a growing sign of maturity and inner strength, beginning to be achieved at last if all too briefly.

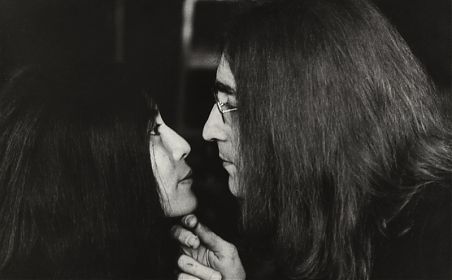

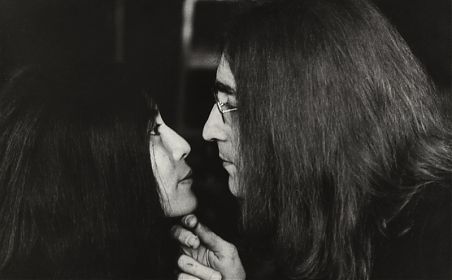

A little old lady from Wigan or Hull wrote to the Daily Mirror asking if they could put Yoko and myself on the front page more often. She said she hadn’t laughed so much in ages. That’s great! That’s what we wanted. I mean, it’s a funny world when two people going to bed on their honeymoon can make the front pages in all the papers for a week. I wouldn’t mind dying as the world’s clown. I’m not looking for epitaphs.

Looking at another hefty chunk of Philip Norman’s John Lennon: A Life, roughly covering 1963-9 – the period which started with the Beatles becoming seriously big, their conquest of Britain and the US and the beginning of their prolific run of brilliant albums, and ended with things going seriously sour, petty and bitter fallings out – the at times acrimonious break up of the band.

Norman continues in his usual self-appointed role of historian, carefully setting out the facts of Lennon’s life and avoiding any temptation to fancy or judgement. As the book continues however, he is unable to resist injecting into proceedings his benefit of hindsight. He’s very quick to find prophecy in spur of the moment quotes, for example Yoko Ono fearing that she would one day end up alone in a New York apartment, and subtle turning points in Lennon’s life. With his relationship with Paul McCartney, 1968 is ruefully labelled “the last year they would be friends”, and of the brief reconciliation between Lennon and his father, “the spell was broken, never to be recaptured”. And at times Norman takes this theme a little too far, finding the song Happiness is a Warm Gun too painful to listen to for its obvious connotations, and constantly nudging us with the fact that – in a few more chapters – Lennon will die.

But despite my nit-picking, I continue to find this a mostly excellent biography. And despite how many Beatle books I’ve read over the years, it is still incredible to believe just how much happened between 1963 and 1969. Putting the output aside, albums and singles in double figures, the films and endless tours (not to mention two books by John as a published author), there is the breathtaking speed of events in Lennon’s own personal life. His increasingly dull married life in rich and comfy Weybridge, controversy in 1966 with the Beatles fleeing the Philippines after seriously p-ing off Imelda Marcos, more trouble in the same year with the “bigger than Jesus” debacle, drugs, more drugs and lots of drugs, the death of Brian Epstein and the Beatles flirtation with the Maharishi. If all these events weren’t enough, Norman spends more time than any on Lennon’s meeting with Yoko Ono…

As biographers go, Norman is extremely kind to Yoko Ono. This is possibly because she contributed to his research for the book, so it’s odd that she eventually withdrew her support claiming that Norman had been “mean to John”. Finishing the story (in the third and final posting) may reveal her reasons why. But Norman gives the best account of their meeting and early relationship that I’ve ever read, revealing it as far more complex than Lennon made out in his later years, when he tended to look back on their courtship with rose-tinted little round glasses.

Factually, Norman has really done his homework here, and I forgive him for misquoting a song lyric or two (In I’m So Tired, Sir Walter Raleigh is a stupid get, not git) and describing the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack as the “accompanying album … selling … five hundred thousand in Britain”. It was a double EP set in this country, Philip, the album came later. Sorry to be pedantic, but you’re getting paid for this mate.

I find myself continuing to read Lennon biographies as I face the prospect of outliving the man for two reasons. They’re both obvious. One is to gain some insight into the creative process of the Beatles, but as this is something that’s been done so well by Ian Macdonald in Revolution in the Head Norman doesn’t attempt to try too hard on this part. His accounts of Revolver through to Sgt Pepper and The White Album – three of the best albums ever made – are sadly pedestrian. Secondly, I just want to find out what Lennon was really like, especially as the memory I had of him (brief though it was) has faded. Norman does this very well, and there are many well constructed memories and accounts of his peculiar yet (mostly) charming personality. So far, he’s not been mean to John.

‘Young man’, he said, ‘understand this: there are two Londons. There’s London Above – that’s where you lived – and then there’s London Below – the Underside – inhabited by the people who fell through the cracks in the world. Now you’re one of them.’

Those bored with Neil Gaiman reviews look away now! Neverwhere is Gaiman’s novel based on the tv series written for the BBC in the mid-90s. But more than a simple tv tie-in, this is a fuller and deeper reworking, allowing Gaiman, as he reveals in his introduction, to fully explore ideas restricted by BBC time and budget. I’m not bored with Gaiman just yet, and I really enjoyed this novel. It creates an eerie yet fascinating underbelly to London, a flipside to the city that’s a dangerous tail to the comparitively safe head of the capital city we know. Into it slips Richard Mayhew, falling from his dull and uneventful office life and through the cracks deep into this world.

Gaiman manages to span the bridge between both his novels and stories for children and for adults. There’s the rich imagination always found in his shorter fiction coupled with his often somewhat darker side, although Neverwhere is much closer to the more mainstream Anansi Boys than say the ultimate darkfest that’s American Gods. As you would expect, the book is full of memorable characters. Take for example Mr Crump and Mr Valdemar, a double act of vicious killers who always claim their prey. Then there is the enchanting but equally dangerous Velvets, Goth-like temptresses who’ll literally suck the life out of you, and a wealth of enigmatic female characters including protector and protected Hunter and Door. In fact Gaiman succeeds in creating stronger females than males; whilst Crump and Valdemar are fun they are simply the stuff of nightmare – the girls are far more rounded and he’s content to get more mileage out of them.

Gaiman also creates vividly memorable situations; the shifting market in this mirror world, the gap (“mind the gap” comes the familiar warning at underground stations, although this is a gap that really bites), the king and his courtiers living on a tube carriage, a bridge where those who cross risk their lives and, in the best storytelling tradition, Mayhew’s own particular initiation through a deathly task that no-one has ever completed before…

So as I’ve said, I enjoyed it very much, and probably the only thing that irked me was Gaiman’s insistence on pleasing an international audience, so London’s inhabitants shop in stores and he feels compelled to explain the most obvious of London’s landmarks, for example Oxford Street. But I forgive him, and I also admire him for not falling into the sequel trap, where lesser authors would have easily wallowed in an entire Neverwhere series.

I didn’t really know what I wanted to be, apart from ending up as an eccentric millionaire. I had to be a millionaire. If I couldn’t do it without being crooked, then I’d have to be crooked. I was quite prepared to do that.

Although I have an unquenchable thirst for anything John Lennon or Beatle related, these pages have been strangely silent over the last two or so years when it comes to the Fab Four. Patiently I’ve waited for a decent new biography to get my teeth into, and now we have Philip Norman’s 822 page John Lennon: The Life. To do Norman’s mammoth work some justice I’m going to spread my thoughts over more than one post. Besides, I haven’t finished it yet. Also I’m away next week and the heavy hardback will take up most of my hand luggage. I’ll have to wait until November to finish it.

There’s been times when I’ve wondered if I’d ever need to read another Lennon biography. I’ve probably read more than my fair share. Strangely, Norman’s other Beatle-themed book Shout, doesn’t stick in the mind much. Ray Coleman’s two biographies of the 80s are much more memorable, and reading them at an impressionable age I held Lennon in the same awe as Coleman. Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon is also unforgettable as it paints such an awful, and often unqualified, picture of him. The Hunter Davies Beatle biography from the late sixties is fun, as is Michael Braun’s Love Me Do, fascinating for being one of the first books published about the moptops. But I suppose my all time favourite is Ian Macdonald’s techy but brilliant Revolution in the Head.

So the question remained, did I need another Lennon book? And reading the opening chapters of John Lennon: A Life I began to worry that maybe I didn’t. A lot of the detail of Lennon’s early life was very familiar, especially his schoolboy exploits with his partner in crime Pete Shotton, and could easily have been cribbed together from the selection of titles I’ve already mentioned. However, Norman kept me reading because I suspected he was looking at this life with the canny eye of the historian. He weighs up the facts carefully and does not commit to making sweeping statements, for example not subscribing to the general view that John’s father was a scoundrel, abandoning the boy and his mother and only returning when he smelt money. Norman draws the picture of a much more complicated story, and for the first time reveals John’s father as not being such a black and white villain, but an unlucky man often prone to unfortunate circumstances.

Norman also handles the well worn legends very carefully, trying to avoid the apochryphal tales. The tragic death of John’s mother when she is run over by an off duty policeman is treated without the sensation of some other biographies, as is the other tragic death in John’s early life. The sudden demise of “fifth Beatle” Stu Sutcliffe aged 22 is related without the usual romanticism, which results in making this loss very moving. And Norman is also careful about the Goldman-fuelled rumour that John was indirectly responsible for his friend’s death by attacking him in a drunken brawl. He doesn’t jump to conclusions about what might or might not have happened because we will never know.

The other turning points in the story arc of the early Beatles are treated with similar care. Norman doesn’t give too much time to the sacking of Pete Best, and, like him, I quietly conclude that it was the right decision to get rid of him. Me, I’m a Ringo man. The supposed gay affair between John and Brian Epstein is also played down; there simply isn’t enough evidence to prove what happened one way or the other. What Norman does do, however, is expose the cruel and dark side of Lennon’s nature that is reliably documented; his violent assualt on a DJ friend that was covered up to avoid a Beatle-ruining scandal, the appalling treatment of Cynthia Lennon, the “secret wife”, and Lennon’s countless affairs.

But he was a mixed up fucker and this made him a great artist. John Lennon: The Life reminded me of one of my favourite books about the 1960s, Dominic Sandbrook’s White Heat. This gives a similarly intelligent, well researched and careful account of legendary, fantastic and life changing events. And you can’t really avoid reading the Beatles and John Lennon story just one more time once you start doing so, especially when it’s put together so well.

Of course I’m only so far; the Fabs have only just released their second album With the Beatles. And listening it again today I’m reminded of its charm, sense of excitement and timeless longevity. So turning the pages still only in 1963 I’ve a long way to go yet. I hope you’ll join me for the rest.

Neil Gaiman is my favourite writer of short stories. His novels are great too, but there’s just something spellbinding about his shorter pieces. The collection Fragile Things was possibly the best book I read last year and certainly one of the best and most memorable books of ghost stories I’ve ever read. The Graveyard Book is his latest work of fiction, and although aimed at a younger readership it still bears Gaiman’s refreshing flair as a gifted writer of supernatural tales.

The Graveyard Book is about a lost child raised by ghosts in an old graveyard, now fallen into overgrown disuse. It’s a simple idea, and its possibly been used before, but only a writer of Gaiman’s class can use it so well. He lets his imagination run with the concept, both through the eyes of the child in question, Nobody Owens (Bod), and through inviting his reader to become immersed in the story. The setting he creates is wonderful, the collapsed and crumbling headstones, the old crypt, the unconsecrated ground, and the ghosts themselves who range from the comic to the creepy. Most of all Gaiman has a wonderful way with words: at one point Bod pauses in conversation to run his fingers over a moss-covered grave, so simply and in so few words reminding the reader they are in the midst of an incredible ghost story.

I’ve mentioned my love for Gaiman’s short stories, and the best parts of The Graveyard Book read like self-contained tales in their own right. Typically for Gaiman, he reveals some of the craft that went into this book in the closing acknowledgments, explaining that he started with the fourth chapter and then later constructed the rest of the book around it. This, The Witch’s Headstone, is a brilliant passage, where Bod encounters and befriends the ghost of a medieval witch. Similarly, another chapter stands out in its own right where Bod plays with a young girl who perceives him as an imaginary friend, only to be found amongst the graves, a friend who’ll fade with memory. Like Gaiman’s best work, it is very touching.

I loved this book throughout, although at times it does feel that Gaiman has strained to wrap a plot around his wonderful prose. I can understand this, as a book aimed at younger readers must appear to be going somewhere, and I may be cynical when I draw comparisons with Harry Potter. But they are there. The child in danger after his parents are murdered, the protection of magic and secrecy, the Dumbledore role as personified by Bod’s guardian Silas. Like Harry, Bod is perceived as a misfit in the “real world”, and like Rowling, Gaiman has a clever line in humour when he portrays those in the magical world who choose to teach and steer our hero.

However, Gaiman has an advantage over J.K. Rowling in that his other fiction is far more varied. Whilst she is yet to branch out from Hogwarts, Gaiman can point his newer readers in the direction of his darker fiction. Passages in The Graveyard Book, in particular Bod’s encounter with the deadly ghouls, recalls the dark and crazy humour of Anansi Boys and American Gods. Most of the readers of The Graveyard Book aren’t quite ready for this very adult stuff, but Gaiman can do that rather wonderful thing in children’s fiction – suggest that there are very broad, challenging and exciting horizons for the reader yet to come.

Previous Page |

Next Page