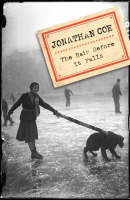

The Rain Before It Falls

Saturday November 17, 2007 in books read 2007 | jonathan coe

The walls and door of the kitchen are painted that creamy, brownish white that was so popular at the time. It was as if people were afraid to let any real light and brightness into their lives – or it had never occurred to them that they were allowed to do so.

Jonathan Coe is an author who just gets better and better. From What a Carve Up!, through to The House of Sleep, The Rotter’s Club and The Closed Circle, I’ve found his fiction always inventive and witty. His latest, The Rain Before It Falls, is his strangest piece to date. Experimental, serious, different, it may prove to be the oddity in Coe’s collected work. Or it may be the beginning of a new, more mature, stage in his writing career.

The novel is written from the point of view of Rosamond, whose first person narrative comes in the unusual form of a set of C90 cassettes found after her death. Even more unusual, they comprise of a series of monologues describing a set of twenty photographs to a blind girl. Coe sets himself a tricky challenge, but one that ushers in many opportunities for the ambitious writer. How we rely on photographs to record the truth and how they never really can, the comparison between amateur snapshots of life (the photograph) with art (a portrait painting), the problems with memory and narrative when emotion clouds and gets in the way, the sober realisation that life is never neat and can never be comfortably catalogued and filed away; it’s all here.

The premise of The Rain Before It Falls is a difficult one, and a less skilled writer could easily get bogged down with the conceit, but Coe manages to use it only as a framing device. The real strength of the novel is the story, with the descriptions of the photographs serving to add a touch of originality. Rosamond unfolds the history of her childhood friendship with the unruly Beatrix, and her subsequent encounters with her family which lead to the tragic story of Imogen, the blind girl in question. Rosumond is full of regret, and longing, and ultimately her efforts lead nowhere; it’s a sad and moving tale.

One of Jonathan Coe’s strength as a novelist is his eye for social history and detail. He doesn’t give the impression that he’s researched anything; he just appears to know his stuff. In one chapter Rosamond describes the interior of a 1950s kitchen. The decor, its limitations, the whole rhyme and reason for it comes alive because Coe just appears to be in touch with this distinct moment in history, a very real and English kitchen; ordinary, drab, but very, very real. He’s also reached the Ian McEwan stage where he can tackle complex ideas quite effortlessly; he makes great writing appear easy. I’m going to be watching his next move very closely.